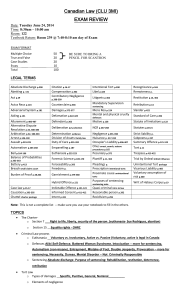

Word Version

advertisement