York in the Time of Henry VIII

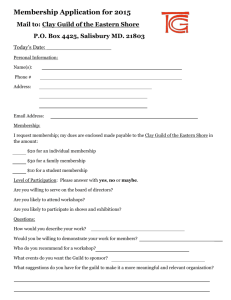

advertisement

The City of York in the time of Henry VIII by Nadine Lewycky Sixteenth-Century England: An Overview Society: The traditional thesis regarding demography was that towns experienced a decline in both wealth and population in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, for example, as was the case in York. However, other towns were prospering at their expense. Halifax and Wakefield in the West Riding were experiencing growth in the textile industry, while Newcastle and Hull were exporting cloth to the continent, again at the expense of York, which lost out on both manufacturing and mercantile activities. Scholars have now revised their interpretation of the condition of early modern towns to be regional phenomena – that is, economic prosperity or decline was experienced by a town and its surrounding countryside, rather than as a town versus rural divide. The demography and social structure in England was also in flux in this period. Towns were either growing or shrinking in size depending on their location and their economic situation. By the Elizabethan period, even those towns that had been experiencing a decline in population under Henry VIII were beginning to recover, if not surpass their previous levels. The rise of mercantile activity in the towns also had an impact on the composition of the social structure – what historians have traditionally referred to as ‘the rise of the middle class’. Merchants and professionals, such as lawyers, became wealthier and more numerous and established themselves in the social hierarchy by purchasing land and estates, which remained the most important characteristic for determining social status and accessing political participation. During this period, the role of the landed aristocracy was changing. With the creation of a professional standing army, in which soldiers were paid a wage, and the use of foreign mercenaries (think of the Swiss Guard), the traditional military function of the nobility receded. Under Henry VIII and his numerous forays into France, the nobility were still expected to provide military service both personally and by enlisting their tenants. During Page 1 of 20 times of peace, the nobility continued to fulfil the role of the king’s natural councillors and were expected to attend the royal court for part of the year. So instead of depicting the place of the nobility in the sixteenth century as declining steadily in absolute terms, we need to see it as fluctuating and relative to the political power and authority of the gentry, who were increasing in number. Mervyn James has also argued for an alteration in the ethos of the nobility – that is, with the re-introduction of humanist values in the Renaissance, ‘nobility’ was determined by education, erudition and virtue more so than blood lines and land. Some landed nobility were able to adjust to the new political and intellectual climate by attending the universities, which laymen did in increasing numbers in the sixteenth century, and by applying this education to the performance of administrative service to the crown. Politics and administration: Politically, England was one of the most centralised kingdoms in Europe, more so than France, although it lacked many of the features which we would recognise in a ‘modern nation state’. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century British historians have regarded the Reformation as the genesis of a polity which we would be recognise today. Controversially, Geoffrey Elton pinpointed this process to the 1530s as the work of Henry’s first minister and Royal Secretary Thomas Cromwell. In the 1960s, G.E. Aylmer studied seventeenth-century ‘civil servants’, but it is generally accepted that historians need to be more cautious about using modern terms, such as ‘bureaucratic’, ‘nation’ and ‘state’ when describing early modern polities and their administrators. Centrally, the kingdom was governed from the royal court, a political institution which developed in all European kingdoms in the fifteenth century. The royal court and the royal household were attached and were essentially the same political body. The household was simultaneously the private, domestic establishment in which the servants provided for the material comforts of the lord, while also being his public, political body, where servants carried out political functions, such as acting as messengers; it was also his political venue, where he received diplomats, guests and colleagues, and conducted his business. Henry’s closest servants were also his advisers. We must remember that categories or terms, such as councillor or adviser, were used loosely – these were not official positions, but the men who were in daily contact with the king and were the most trustworthy normally provided the king with advice on how to govern. The royal household and the court were the venues in which the king maintained contact with the realm. Both of these bodies – household and court – should be conceived of as changeable entities – they were collections of persons surrounding the king rather than physical locations. The membership of these bodies was fluid and the court and household were peripatetic – that is, they moved with the king on his progresses around the kingdom. As I just mentioned, it was the court and household, which linked the king with the outlying areas of his kingdom. The household was the core of what scholars have called the ‘king’s’ or ‘royal affinity’. It was comprised of men who were in the king’s service, including those most intimately attached to the king: councillors, privy chamber servants, central officials and nobles residing at the court. But the royal affinity extended beyond the court and also Page 2 of 20 comprised men who governed throughout the kingdom. They were connected to royal government in a variety of ways: some men were knights of the shire (that is, they sat in parliament); some men were county officials, such as escheators or sheriffs; others were justices of the peace or assize. This was the second degree of attachment to the king. They held regular offices and received regular payments. But not all held positions in which they were expected to undertake administrative duties. There were men from the provinces who were attached to the royal household on an irregular basis and were called the king’s knights or yeomen of the crown, depending on their social status. They may be called upon to act on ad hoc commissions when necessary, such as collecting taxes, and to serve the king militarily in war. These men were given ‘supernumerary’ offices – for example, knight of the household, although they were not expected to attend the court for lengthy periods of time nor did they actually hold an office. Thus, while England was a centralised kingdom, it was not what we would recognise today as a modern nation-state, the type of polity which emerged in the nineteenth century. Rather, it was governed from the centre by socio-political networks in which men in the provinces provided the king with service, be it administrative, military or otherwise, in exchange for rewards, such as grants of land, office, cash or favours. The ability to lavishly reward his subjects was the lynchpin of this type of government; and Henry’s ability to reward his servants increased dramatically after the monastic dissolutions of the 1530s. It altered the power dynamics in the kingdom dramatically – not only between church and state, but also within the social hierarchy. England under Henry VIII was a personal monarchy – the personality of the king influenced the nature of government, and the strength of its government rested on the quality and ability of the gentlemen in the provinces, rather than on an institutionalised network of bureaucratic offices. Religion: There were two strains of attack on the church in England and the traditional form of religious practice in the early sixteenth century: the first was Lollardy, a domestic heretical movement which had been present in England since the fourteenth century; and the second was evangelicalism, in particular, Lutheranism which was entering England through trading ports with Europe. (Evangelicalism stressed the primacy of scriptural and biblical doctrine, and is best known for the concept of salvation by faith, which downplayed the efficacy of good works and purgatory as promoted by the medieval church.) It may be surprising to learn that members of the church hierarchy considered Lollardy, rather than Lutheranism, the greatest threat to traditional religion in the 1520s. That is because bishops, deans and other officials believed that Lutheranism would re-ignite dormant Lollard sects. Historians generally agree that Lollardy had died out in England by the sixteenth century, but it was perceived to still be a problem. Thus, the campaign against heresy in the 1520s led by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Chancellor of England, which included public book burnings and trials of heretics, was spurred by the fear of Lollardy. Further, the campaign to squash heresy was directed at scholars at the universities, rather than at ordinary laypersons. The exception was the foreign merchant communities in London where the Lutheran-style evangelicalism was popular. There has been a lot of scholarly debate about the state of the church and its ability to provide adequate spiritual guidance to people in the early sixteenth century. Formerly, historians Page 3 of 20 argued that the church was crumbling and that its religious provisions were insufficient because they were provided by inadequately trained clergy. This view has largely been revised. Historians now believe that pre-Reformation religion satisfied the spiritual needs of the majority of English people. It was a multifarious and fluid type of spirituality, and it involved a large amount of lay participation, through religious guilds, passion plays and popular feast days, such as Corpus Christi. Similarly, the monastic orders have not traditionally received favourable reviews from historians. The monasteries were interpreted as being in decline and in need of reform, thus justifying the dissolutions of smaller houses which began in the 1520s with Wolsey’s foundation of Cardinal College (now Christ Church) at Oxford and continuing in the large scale dissolutions of the mid to late 1530s. Revisionists, like Eamonn Duffy, have argued that monasteries were in much better spiritual and financial health than has previously been assumed. While the church and the monasteries were by no means perfect, the state of them was not so deficient as to warrant full-scale dissolution. Instead, historians are arguing that what is significant about the early Tudor period, is the change in people’s expectations of their clergy and the monastic orders: the introduction of humanism along with an increasingly educated lay population who desired a greater involvement in religion, meant that the secular and regular clergy were under greater scrutiny than ever before. Humanism: The introduction of the intellectual movement of humanism, both from the Italian and Northern European Renaissance movements, was essential to determining the course of the Reformation in England. The central tenet of humanism was a stress on the humanity of Christ (the man) and ‘humanist’ scholars were those who advocated the study of scriptures in their original languages, Greek and Hebrew, a study of Greek authors, because of the emphasis on human society in their writings, as well as a focus on rhetoric and grammar. This would enable society to re-establish a ‘pure’ church, as well as being practically useful by preparing men to be eloquent diplomats. Thus, the reformation in England was a mixture of political and dynastic events unique to England, but it was also part of a larger European-wide movement of reform directed at doctrine and religious practice. York: An Introduction York’s history as a city began in 1212/13 when King John granted it freedom from the financial control of the county sheriffs and the citizens elected a mayor. At several times between 1296 and 1336 during the reigns of Edward I and Edward II, York served as the kingdom’s capital, playing host to several central government bodies, including the courts of Exchequer, Chancery, King’s Bench and Common Pleas. The city achieved its widest level of freedoms in grants from Richard II by the end of the fourteenth century. They were permitted Page 4 of 20 to elect their own Justices of the Peace in 1393, but the pivotal year was 1396 when Richard gave the city the status of a county: the mayor acted as escheator and the city elected its own sheriffs (2) in place of the High Sheriff of Yorkshire. York and Richard III The legacy of Richard III looms large in the history of the city of York. Created the Duke of Gloucester at the age of 8 by his older brother, Edward IV, Richard assumed his responsibilities as Duke at the age of 18 which involved governing the north of England virtually single-handedly. His royal blood, extensive estates and authority over powerful local individuals meant that Richard was a welcome and important ally to the city in the competition for royal privileges and favour. There is evidence that Richard’s influence was being felt in the city around 1475, and the relationship only became closer throughout the years, as the city sought the Duke’s intervention with the king and in local disputes; and in return Richard requested the city provide soldiers, which they did on numerous occasions. On Gloucester’s appointment as Protector to his young nephew Edward V, the corporation tried to take advantage of the duke’s position and asked for their rent paid to the king (the fee farm) to be reduced. Cities and towns which had been granted ‘county’ status were required to pay the king a fee, but because of the deterioration of the city’s economy, York found it increasingly difficult to meet its financial obligation. On this occasion, Richard refused to grant the city’s request. Shortly after Richard succeeded his nephew to the throne, the city entertained the newlycrowned Richard III and his queen during which time he lavished the governors with gifts and founded a college of chaplains. At this time, Richard met with the mayor and commonalty in the chapter house at York Minster on 17 September 1483, the outcome of which may have been to alleviate the city from paying its rent to the crown. But the result of this meeting was ambiguous, and the city was never able to get confirmation of the grant in the exchequer. Nevertheless, the city continued to grant Richard’s requests, such as those to provide soldiers, and the city sent troops on Richard’s behalf to the fatal Battle of Bosworth in 1485 which was won by Henry Tudor (Henry VII). York’s lingering affection for Richard III meant that the city did not welcome Henry VII with open arms, and the corporation clashed with the founder of the Tudor dynasty on several occasions, refusing Henry’s nominees for the offices of recorder and sword bearer numerous times. Henry visited the city in 1486 and 1487 with the intention of securing the loyalty of its leading citizens, and his journey to York in 1487 was the last by a monarch until his son’s progress in 1541. Government: The corporation which governed the city of York was directly responsible to the king, bypassing the authority of all other royal bodies, with the exception of the Council of the North. York was governed by a corporation made up of the mayor, 13 aldermen (including the mayor), 2 sheriffs, 3 chamberlains, a council of Twenty-Four, the city’s legal officer called the recorder, a common clerk, and a common council, also known as the commonalty Page 5 of 20 or 48, although it rarely contained that number, which represented the city’s guilds. By the Tudor period, civic government had developed into a mercantile oligarchy in which the important offices were monopolized by members of the city’s wealthiest merchant and trade guilds. The office of mayor was one of great dignity and authority: he was the embodiment of all the ancient rights and privileges belonging to the city, and it was his duty to defend these against outside interference. He was personally responsible to the king for maintaining order in the city and, with the aldermen, acted as Justices of the Peace dispensing royal justice. Annual elections were held on St. Blaise’s Day (February 3) from at least as early as 1343. From 1392, no mayor was permitted to be re-elected without all of his fellow aldermen having served first, and therefore in the Tudor period, it was unlikely that any alderman would serve as mayor more than once. The candidates for mayor were restricted to the serving aldermen, the majority of whom were merchants rather than craftsmen, and this meant that York was governed by a mercantile oligarchy. In 1365, the mayor was granted the right to a mace bearer, and in 1388 the city was granted a sword and bearer by Richard II. A further symbol of his authority was the granting of the title Lord Mayor in the 1480s, a privilege shared only by their counterparts in London. The mayor earned a salary of £50 a year, but this amount was not enough to balance the personal outlay of the mayor, who was expected to entertain his fellow city councillors, and local nobles and dignitaries out of his own pocket at a level befitting an important local government official. He was also required to account for any short fall to the king in the city’s accounts. No wonder York’s citizens avoided holding this position, opting to pay the fine for refusing to take office, rather than being burdened with its responsibilities and expenses. Shardlake and Barack first see York’s Lord Mayor, Robert Hall, as he is making preparations for the progress (for more on the city’s preparations, visit the York City Archives Exhibition, (title), in the York Central Library). The mayor was outside a candlemaker’s shop, ‘in a red robe and broad-brimmed red hat, a gold chain of office round his neck….Three black-robed officials stood by, one carrying a gold mace.’ (p. 47) The Mansion House, which now dominates St. Helen’s Square, was not built until the mid eighteenth century, and thus, the Tudor Lord Mayors of York did not have an official residence. Proposals to build an official residence for the Lord Mayor were being considered in 1723, but the construction of the house was not complete until 1730 when the first Lord Mayor moved in, and even then, the decoration was not finished for another two years. In the mid eighteenth century, the Lord Mayor maintained a substantial household at the Mansion House consisting of a chaplain, a town clerk, the sword bearer, four mace bearers, as well as a collection of everyday household servants. Disputes arising from mayoral elections were a common occurrence throughout York’s history and one particularly ‘riotous’ election in 1516 paved the way for permanent change to the city’s constitution. Following the death of Alderman John Shaw, two men, John Norman and William Cure, received an equal number of votes for the vacant office. The result sparked rioting in the city and Henry VIII issued a commission to local Justices of the Peace to inquire into the disturbances. Having determined that a division among the aldermen was likely to cause more trouble in the city, they commanded that the opposing sides choose representatives to appear before the king’s council in April. The council nullified the election and commanded that no man be elected to the office without their consent. The following Page 6 of 20 January when a second aldermanic office became vacant, the corporation proceeded to elect both men to the two open positions, thereby solving their previous impasse. The corporation also voted in a new mayor, William Neleson, who was at the time incarcerated by the crown in Fleet prison for debt. Infuriated by this affront to royal authority, the king sent an angry letter to the corporation appointing a new mayor and ejecting Norman and Cure. The whole affair prompted Henry VIII to issue York a new civic charter which regulated the election process and prevented crowds from gathering on the day for elections. Letters Patent issued by the king on 18 July 1517 established a common council to represent the city’s crafts, and although historians have depicted this as a step towards democratic government in York, the day-to-day administration of the city largely remained in the hands of the city’s executive offices. Like the mayor, the city’s two sheriffs were elected annually and were only expected to hold the office once, the post being a stepping stone into election as an alderman. The sheriffs assisted the mayor in carrying out his duties and exercised a range of judicial functions; were responsible for regulating the city’s markets and rules governing the sale of ale and bread; and possessed their own prison and court which was separate from the prison of the High Sheriff of Yorkshire located at York Castle. Like the other chief civic executives, the sheriffs were expected to entertain the city dignitaries annually and to conduct themselves in a manner befitting important civic officials, meaning that the post carried great personal costs. The sheriffs also had to support an entourage of personal and official servants, including mace bearers and clerks, who assisted in performing the sheriffs’ duties. The city finances were under the supervision of three chamberlains. When the city was experiencing economic decline in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the chamberlains found themselves continually short of money for day-to-day expenses, and had to meet these out of their own pockets. The Recorder of York was the city’s official legal counsel. In 1385 an ordinance was issued providing for a recorder ‘with knowledge of the law and of good repute’. Unlike the other civic offices in the city, the recorder was usually a practising lawyer who lived in the nearby countryside. The appointment was for life and the officeholder received an annual salary of 20 marks. Many recorders went on to become royal judges. Shardlake first meets the city’s recorder, Master Tankard, on his way to the Guildhall to find the coroner (p. 88). The other professional office in York was the common or city clerk. This position existed from at least the early fourteenth century. In the later middle ages, the clerk was frequently a churchman who had attended university but by the Tudor period, the clerk was usually a literate citizen, such as a lawyer or merchant. Normally, the office was occupied by a city freeman, however, Richard III pressured the corporation into appointing his nominee who did not reside within the city. Other minor officials assisting in the government of the city included three coroners, muremasters (responsible for maintaining the city’s walls) and bridgemasters, who kept the city’s bridges and for collecting tolls. Within the city, there were further administrative divisions. The city consisted of 6 wards under the supervision of sergeants. These sergeants were assisted in their duties by two aldermen and additional wardens. Within the wards, the officers carried out military duties, Page 7 of 20 such as raising troops, arms and money; opened and closed the city gates; and kept the walls clear of rubbish. The smallest administrative unit in the city was the parish, which was under the supervision of a clerk and two or three constables. The constables were chosen annually and performed a variety of functions including: keeping the peace and serving justice; carrying out orders from the mayor; cleaning the pavements and clearing the air of foul smells; and assisting in raising troops and money for war. The City of York was represented by two Members of Parliament who sat in the House of Commons. The MPs were elected by members of the city council and were usually the incumbent mayor and one of the aldermen. In 1539, the MPs were John Hogeson and William Tancred. Representation in parliament was clearly valued by the corporation since they paid their MPs 4s per day, twice the amount required by statute. The city council regularly met in the council chambers which were located on Ouse Bridge until they were demolished in 1810. From 1811, the council has met in the Inner Room of the Guildhall. Having fiercely guarded its right to self-government throughout the later middle ages, the corporation and the Council of the North were often embroiled in jurisdictional disputes, once the council permanently sat at King’s Manor. In the aftermath of the Pilgrimage of Grace, however, the Council’s authority was strengthened at the city’s expense. The relationship between the Council and York’s corporation was not always characterised by jurisdictional conflict. The corporation was well aware of the value of having such an important royal institution in the city – since it stimulated the economy by bringing dignitaries, litigants and trade to the city – and the governors commonly bestowed gifts upon the council members and their families. The city and the council were also able to act in cooperation on the city’s internal matters, such as removal of fishgarths from the river, or dealing with improper conduct by aldermen and freemen. Economy: The success (or failure) of York’s economy was dependent upon several converging factors: firstly, the city was an ecclesiastical and administrative centre. It was the seat of the Archbishop of York, possessed a large and wealthy cathedral, and on various occasions throughout the later medieval and early modern periods, hosted institutions of royal government. These church and state institutions attracted visiting legal officers and church and government dignitaries, and litigants to its courts, and all of whom would have required food and lodging provided by armies of traders and merchants. Second, York was wellpositioned for internal and external trade, being located on the intersection of two rivers. It acted as a local distributive centre for goods coming from London to its surrounding areas, and as a market town for local trade and agriculture. Lastly, its position close to the AngloScottish borders meant that the city was used by royal armies heading north to the border towns and garrisons of Carlisle or Berwick-upon-Tweed, and local masons and carpenters were employed on constructing tools for war. Unlike England more generally in the fourteenth century, the economy of the city of York was prospering. York not only survived the economic and social disruption caused by the Black Death which made its way to Yorkshire by March 1349, but flourished in its wake, as Page 8 of 20 immigrants from the surrounding rural area inflated its population, and York was the seat of the export cloth industry until the end of the century. Its prosperity is reflected in the amount of building that went on inside the city at this time. By the beginning of the fifteenth century, however, the recession that had been affecting the rest of the country finally penetrated York. Property values and rents within the city dropped, and many tenements became derelict. Having ranked as the second most prosperous city in the kingdom behind London on the tax assessment of 1377, by the sixteenth century, York ranked fifteenth, behind such towns as Bristol and Coventry. This economic decline resulted primarily from the declining importance of the textile industry which was facing challenges from nearby towns in the West Riding, such as Halifax and Wakefield, as well as from the continent. The trades most seriously affected were those who worked with textiles: the dyers, drapers, weavers and tailors. Also badly affected were the leather industry and metalworking. The economic situation in the city was likely worsened by the adoption of more stringent regulations on trade and manufacture by the craft guilds, rather than an opening up of the market to make it more accessible to a wider range of practitioners. Crafts and Guilds: Craft guilds were associations which possessed exclusive rights to practice their particular craft within a city’s or town’s jurisdiction. They were formed to protect the interest of those who laboured in that trade. Although the guilds appear from a distance to be highly protectionist, and in many ways they were, there was some collaboration and overlap between guilds in which the craft workers used similar tools or materials, thus leading to amalgamation of some guilds over time. The internal organisation of guilds was determined by its ordinances which were endorsed by the city authorities, thus placing the guild ultimately under the authority of the city council. Thus, the mayor could command that a guild meeting be called if an issue arose. While the exact details of each guild government was different, all guilds had officers called searchers, who were the most important officers. Their duties included essentially enforcing the guild’s ordinances: summoning meetings, managing finances, inspecting the quality of goods manufactured and sold by guild members, approving the skill of new masters, authorising apprentices, and enforcing wage regulations. The guilds also played an important role in the social life of the city. They augmented the religious life of the parishes. All guilds were dedicated to a patron saint, such as the Merchant Taylors (see below), whose patron was St. John the Baptist, and carried out charitable functions for poor, elderly or infirm guild members, which extended to helping to pay burial costs. Their most prominent religious function was staging individual pageants which comprised the Corpus Christi plays. The first recorded production of these pageants dates from 1376 although it is likely that they had been performed for some years previously. The money to pay for the performance of these plays came from annual contributions by guild members and a certain percentage of the fines for breaking guild regulations. The Corpus Christi plays continued to be performed in almost their original form until the reign of Elizabeth I, when they were considered both an unnecessary financial burden, and an embarrassing reminder of the city’s ‘backward’ religious orientation. Although these guilds had a religious function, it is important to distinguish them from purely religious guilds, such as the guild of St. Christopher and St. George in York, which were dissolved with the Page 9 of 20 chantries in the 1540s. Like craft guilds, religious guilds also offered their members a social structure and sense of belonging, and financial support in difficult times. Of the over 80 craft guilds which existed in York in the fifteenth century, only one, the Merchant Taylors, survives today. Although the craft was present in York in the thirteenth century, it seems that a guild did not form until the following century, when it first appears in the city’s official records in 1387. There was a sharp increase in the number of tailors practising in the city in this period, and the incorporation of a guild likely reflects this trend. First references to a separate hall for the Merchant Taylors dates from the early fifteenth century, and shortly thereafter, also to a maisondieu or almshouse, where sick or infirm members of the guild would be look after. The hall still stands in the Aldwark area of York where it was originally built, although it has been much modified and enlarged throughout the years. The Great Hall was built in 1649 and rebuilt in 1725. Also, in the early eighteenth century, the medieval almshouse was demolished and replaced by the current structure. At this time, the Hall was also given its brick façade. In 1887, the archway which obscured the front of the Hall from public view was demolished. Restoration work was undertaken after World War II. As mentioned above, the Merchant Taylors were dedicated to the patron saint of St. John the Baptist. The Confraternity of St. John the Baptist started as a separate religious guild, but by the mid-fifteenth century, the membership had become dominated by tailors who took control of it. The religious functions of the confraternity were incorporated with that of the craft guild that the survey into chantries, fraternities and guilds in 1548 did not even mention a guild dedicated to St. John the Baptist. In 1518, the Merchant Taylors were one of the largest trade guilds in York, and in 1551 they absorbed the drapers’ guild whose numbers were declining. By 1585, the guild also included the hosiers, although this amalgamation of several trades did not stop the general decline over the next few centuries in the wealth and importance of the guild in the social and economic life of the city. Merchants and Trading: Like the crafts, the merchants of York experienced a period of prosperity in the fourteenth century. Although primarily trading in wool and cloth, York merchants traded a diverse range of natural materials. Being situated on the Ouse River meant that the city was an important trading hub, both locally and internationally. Like the trades, however, York merchants were experiencing economic contraction in the fifteenth century, brought about partly as a result of competition for European markets with Hull and the London Merchant Adventurers. Because of their relative decline, merchants of York were in a constant struggle with their counterparts in the nearby cities of Hull and Newcastle over trading privileges to the continent. Despite the overall decline in trade which passed through York, it remained an important trading centre throughout the sixteenth century and its merchants traded with Netherlands, northern Germany and the Baltic. In the later fifteenth century, lead had become York’s largest export, however, in an attempt to re-establish itself as the centre for the wool trade, the city acquired a royal monopoly for shipping Yorkshire wools and fells overseas in 1523. This action was unsuccessful and was challenged by the merchants in London until it was repealed in parliament in 1529. Further, York had ceded its dominance in the lead trade also to the London merchants. Page 10 of 20 Founded in 1357, the Merchant Adventurers were originally a religious guild dedicated to Our Lord Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary. The original charter outlined the guild’s structure which was made up of a master and thirteen members drawn from various crafts and trades: mercers, drapers, hosiers, dyers, and the woollen industry. The previous year, in 1356, the group had already received a grant of land on which to build a common hall, the site where the hall still stands. In the early years, the guild was attracting members from all over Yorkshire, including Whitby, Newcastle and Hull, a fact which was not unusual in this period, as the larger guilds often had members from outside the city, but certainly indicates that the guild was both large and popular. The guild also possessed a hospital under the care of a master and chaplains which was to care for thirteen poor and feeble residents and two poor scholars. By the early fifteenth century, the majority of its members were merchants, and so the guild also established ordinances for trading. In 1430, the Mistery of Mercers received a royal charter of incorporation from Henry VI. The merchants engaged primarily in overseas trade with northern Europe and the Baltic area in wools and cloth, but also in lead in the sixteenth century. By this point, the original religious functions of the guild had been so completely subsumed under its economic functions, that the dissolution of chantries, guilds and fraternities in 1548, had virtually no impact on the wealth of the company whatsoever. The company’s present buildings were built between 1357 and 1361, making it one of the earliest guild halls in the country. It was built on top of the remains of a Norma mansion. Like the Merchant Tailors, a hospital was constructed on the site for ministering to the company’s elderly, inform or poverty stricken members. Various additions and enlargements were made throughout the following centuries, and extensive reconstruction was carried out in the twentieth century. By the seventeenth century, the company also owned a hall on Ouse Bridge where it held meetings until the bridge was rebuilt in the early nineteenth century. Afterwards, the company met in the Guildhall in Coney Street. Religion: The York skyline has been dominated by a cathedral since the construction of the present Minster between 1230 and 1472, although the history of the church in York has a much longer history, dating before the Conquest. The original church at York was a timber-framed church constructed for the conversion of Eadwine, king of Northumbria, to Christianity in 627. This baptism was performed by the bishop of York, Paulinus, a monk who had come to England to support Augustine’s mission to convert the isle to Christianity. The elevation in York’s status to an archbishopric in 735 had been a long time coming: Pope Gregory the Great, who had commissioned the missionary movement to Britain in 597, had set out a plan in 601 to have the island governed by two archbishops, one in the south at Canterbury, and the other in the north at York. York Minster was administered separately from the archdiocese, however, the same men often filled both sets of positions. The cathedral was governed by a dean and chapter comprised of canons. The chief offices were the dean, chancellor, precentor, treasurer, and a subdean. Statutes passed in 1222 required that these dignitaries reside at the cathedral (except Page 11 of 20 when required by official royal duties), however, Brian Higden, who was dean from 1514 until his death in 1539, was unusual in the fact that he did reside. All of these positions were appointed by the archbishop, with the exception of the dean who was elected by the canons, however, in practice, the archbishop usually dictated the outcome of the election. The 36 canons also held prebends which were pieces of land and property which accompanied their canonries from which they derived their income. The number of canons in the Minster currently stands at 30. The dean was the most important officer in both the management of the Minster and in the religious ceremonies taking central position in all important processions and religious celebrations. He presided over meetings of the chapter and admitted men to the cathedral prebends and dignitaries. The precentor was responsible for the recruitment and training of choristers, and the singing during services, however, his duties were often carried out by a deputy, known as the succentor. The Chancellor was primarily responsible for the educational and intellectual life of the cathedral, which included appointing the master of the grammar school, and thus the office was typically filled by a renowned scholar. The Chancellor was also required to preach during services on the first Sundays of Advent and Lent. Like the other major offices in the cathedral, the Chancellor had a deputy to carry out his duties, particularly assigning the readings in the choir and supervising the deacons. The office of treasurer was one of the wealthiest church offices in England, and thus was often held by royal servants and diplomats as reward for their services to the crown. The subtreasurer carried out the treasurer’s duties in practice, providing the items necessary for worship, such as candles and altar pieces, cloths and plate. St. William’s College was founded in 1461 to provide accommodation for the chantry priests of the Minster and the present building was constructed between 1465 and 1467. After it fell into crown hands as part of the dissolution, the crown let it out to private individuals throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, during which time it underwent extensive internal alterations. It was bought by the York Convocation in 1906 and used for its meetings until it was converted into the conference centre and tea rooms for the Minster. For the most part, the present Minster resembles that as it stood in the fifteenth century, although it has been extensively repaired. For example, the stone choir screen with statues of medieval English kings, was constructed between 1475 and 1505. York Minster has fallen prey to fire repeatedly, including several times in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, and most recently in 1981. The dean and chapter had jurisdiction over the area surrounding the church and all other property they owned, known as the Liberty of St. Peter. The exact dimensions of the liberty surrounding the church are not certain, but it is believed to have included the nearby city walls and Bootham Bar. It contained a churchyard and the parish churches of St. Michael le Belfry and St. Mary-ad-Valvas, as well as shops, tenements, and houses. Shardlake notes the buildings which line along the wall at the edges of the precinct (p. 12). In this area, the dean and chapter had authority over civil and criminal law which they exercised through two courts. These courts dealt with matters relating to the clergy, such as enforcing clerical Page 12 of 20 discipline and registering their wills; and issues from the general public which fell within the remit of canon law: disputes over wills, matrimonial cases, adultery, slander, defamation, perjury, non-attendance at church, and Sunday trading. The area under the control of the Minster was greatly altered by the Reformation, however, a list of properties drawn up in 1789 shows that the dean and chapter still owned 168 properties. The courts continued to function until 1846. The precinct also possessed a gaol to house offenders, called Peter’s Prison. In Sovereign, the York lawyer Giles Wrenne lived inside the Minster Precinct along with the city’s other senior lawyers (p. 7). Since the twelfth century, the Archbishop’s Palace also stood within the liberty. It was a victim of the austerity of the post-Reformation period when Archbishop Young began its destruction in the 1560s. It was sold to a county gentry family, who divided the palace grounds into smaller units for letting. It was purchased by the Minster chapter in the early nineteenth century, and forms part of what is now known as the Dean’s Park. The Dean’s Park itself was created out of the Minster precinct at the same time. Because York Minster was a secular cathedral, that is, the canons were priests and not monks, it was partially sheltered from the early stages of the Reformation in which monastic property was confiscated by the crown. By the 1540s, however, York was beginning to experience changes in both the fabric and order of worship. In 1541, a statue of Henry VI was removed from the stone choir screen (the current one was replaced in 1810) and during his progress to York in 1541, Henry VIII ordered that the shrine dedicated to St. William (a former archbishop of York) be pulled down (pp. 426-7). The relics, treasures and plate belonging to the Minster were confiscated by the crown, and the chantries were removed in 1547-8. After the introduction of the revised Prayer Book in 1552, the walls were cleansed of their paintings and images and monuments removed. In 1544, religious services were read in English, and the Prayer Book of 1549 was adopted. However, the Minster eagerly joined in the re-introduction of Catholic practices under Mary, re-decorating the walls and adorning the altar. It was not until the appointment of Matthew Hutton as dean of York in 1567 that Catholic practices truly came to an end in York Minster. The High Altar was removed in 1580. In addition to York Minster, the city was home to an abundance of parish churches, hospitals, religious houses, mendicant orders and religious guilds. The largest religious guild in the city was that of SS. Christopher and George which attracted wide support among the laity and clergy. Between 1408 and 1546 the guild had nearly 17,000 members, including archbishops, bishops, abbots and priors. The famous York Corpus Christi play was being held at least from the 1370s and the earliest detailed account of plays from 1415. By the Elizabethan period, the plays were becoming both a financial burden on the citizens and an embarrassing reminder of the city’s religious conservatism and social backwardness, and the city cancelled the performance of the plays in the 1570s. In the early sixteenth century, the citizens of York demonstrated a strong attachment to their local churches, as evidenced by the bequests made in their wills. Most bequests were made to the city’s mendicant friars, rather than the religious houses, which was typical of the country as a whole. Beginning in the mid fifteenth century as well, York citizens were less likely to leave bequests to found perpetual chantries. Founding chantries by bestowing land, property and money to support a priest to say prayers for the health of the founder’s soul and the souls Page 13 of 20 of his family members, was a common practice among the ruling elite in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. However, the economic decline experienced in the city meant that by the end of the fifteenth century, foundations of this sort were too expensive for most people. In the chantry survey of 1548, there were 38 chantries in York Minster which had been founded by the cathedral canons, and a further 39 spread throughout the parish churches, but these had all been founded before 1500. After that date, only one chantry was founded by a York citizen. In the early sixteenth century, however, there had certainly been more chantries in the city since seven had been dissolved by the city council in 1536 (likely because their upkeep had become a financial burden). Barry Dobson has speculated that it is possible the city once contained as many as 140 chantries. What is striking about a city so much dominated by the church, such as York, was the poverty of the city’s priests and chaplains. Chantry priests were expected to receive a statutory minimum wage of 5 or 6 marks a year, but many chantries in York were worth less than this in the sixteenth century. Overall, the urban clergy were poorer and less educated than their rural counterparts, since the smaller income of urban parishes did not attract the best candidates. Urban parishes were worth less because the majority of clerical income came from tithes, which were significantly less in cities. Urban priests also relied more on monetary gifts, which were declining as the economy weakened. The limited trading links between York merchants and the continent by the sixteenth century is one factor in accounting for the continued religious conservatism among the citizens of York. Although there appears to have been a revival in the thirteenth century heresy Lollardy in the 1510s and 1520s, it does not appear to have links with the reforming movement occurring simultaneously on the continent. Another factor is the overwhelming presence and authority of the archbishop and the cathedral within the city. From 1531 until 1544, the archbishop of York, was Edward Lee, a man who held conservative religious views. Studies have shown that many former monks remained in Yorkshire after their houses were dissolved and took up places as chantry or parish priests. Undoubtedly, their continuing presence contributed to the conservative nature of religion in the region. This is also true of many of the city’s parish priests who were, perhaps, so low down the socio-economic scale, that they could continue in their posts regardless of the religious orientation of the reigning monarch, whether Catholic or Protestant. This is not to say that the citizens of York were completely oblivious to religious dissent: there is evidence of Lollard-style heresies circulating in the city in the sixteenth century and citizens were certainly aware of the continental trend of ‘new learning’. It is worth remembering, however, that those individuals who expressed an interest in re-reading the scriptures in their original languages, or even in advocating for religious services to be held in English, does not meant that they adhered to Lutheran beliefs or supported the break from Rome. Decline and Recovery: Page 14 of 20 The fortunes and quality of life in England’s cities during the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries fluctuated depending on a number of factors. Medieval peak of prosperity had been based on trade, manufacturing and administrative; revived prosperity from service industries, social life and administration. In the mid fifteenth century, York had been the largest town in the north of England. The failure of York’s merchants to get a foothold in the textile industry made a significant contribution to the city’s decline in wealth, population and status in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Decline in clothmaking and long distance trade were key elements in late medieval decay in York; part of process of most trade going through London. Great medieval and ecclesiastical towns, such as Lincoln, Winchester and Oxford, were having difficulty competing with London and the newer trade and industrial centres such as Halifax and Wakefield. Despite experiencing a significant contraction in the size of its population, shrinking from 12,000 to 8,000 people by the 1520s, the population of York began to recover in the Elizabethan period, reaching levels of 11,500 by 1600 and 12,000 by 1630. It is not accurate to say that such economic and demographic problems were only in towns, but rather rural areas also experienced mass depopulation as many peasants migrated to larger towns and cities in an attempt to secure work. After having entered the city, Barack noticed that the market place was looking poor. Shardlake points out that trade in York had been bad for years (p. 10). Impact of the Dissolution: The dissolution of the monasteries which took place in the later 1530s and the dissolution of the chantries which followed in 1547 and 1548 had a significant impact on the social, mental and physical landscape of the city. The city and the county were remarkable for the high presence of members of the religious profession. There were houses belonging to all the monastic orders, all 5 orders of mendicant friars, 3 major hospitals, and over 20 minor hospitals within the city. In 1539, St. Mary’s Abbey was surrendered by the last abbot, William Thornton, and the house’s 50 inmates were each given a pension and dismissed. The abbot’s residence was converted into the headquarters of the Council of the North which had been sitting permanently in the city since 1537. This building became known as the King’s Manor, as it still is today. Because of the direct relevance to people’s lives (and souls) the elimination of purgatory from the doctrine of the Anglican, and therefore prayers for the dead had a significant impact on the structure of religious practice at the local level. This meant that chantries and their priests ceased to serve a useful function, and their dissolution in 1547-8 had a more direct impact on the city’s inhabitants than the dissolution of the monasteries. As a consequence, the college of vicars choral, St. William’s, was closed and sold into private hands in 1549. This doctrine also undermined the justification for religious guilds, and the guild of Corpus Christi was dissolved in 1547. The guild of SS. Christopher and George endured slightly longer; despite the guild masters having been brought before Star Chamber on charges of corruption in 1533, the guild continued to perform its duties to the poor until its properties were sold in the spring of 1549. Page 15 of 20 The dissolution of the city’s religious institutions had a knock-on effect on the city’s economy, a fact which Shardlake alludes to on page 10. The monasteries had provided a significant market for traders and manufacturers in cloth, building materials and foodstuffs. With the destruction of the various shrines in the city, particularly St. William’s in York Minster, the number of visitors to the city declined as the pilgrim trade was eliminated. The Pilgrimage of Grace: Undoubtedly, the largest consequence from the dissolution of the monasteries was the rebellion it inspired in Lincolnshire and the northern counties in the autumn of 1536 and early 1537. An uprising erupted in Lincolnshire on 1 October 1536 when up to 40,000 nobles, gentry and commoners marched to the city of Lincoln. News of the protest spread north where men from Durham, Lancashire and Northumberland joined rebels from Yorkshire who convened at York on 16 October. Under the leadership of Yorkshire lawyer Robert Aske, the force of 10,000 strong rebels then marched on Pontefract Castle, which they took following a short siege. There they were met by the Duke of Norfolk and the Earl of Shrewsbury sent by Henry VIII to dispel and prosecute the rebels. Aske and his fellow leaders (a total of over 200 men) were executed for treason for their part in the rebellion. Aske was hanged by a chain outside York on 12 July 1537, where his bones still hung when Henry and his progress came in 1541 (pp. 35, 41-3). Sir Robert Constable was also executed for his part in the rebellion and his bones were still hanging outside Hull when the progress arrived there (p. 431). The motivations behind the pilgrimage are various, and it is likely that the commons and gentry had different priorities. Among these demands, the restoration of the north’s monastic houses was prominent, as was the demand that Henry cease taking the advice of evil counsellors, such as Thomas Cromwell, who orchestrated the closure of the religious houses. Complaints about recent excessive taxation also featured, alongside a request for parliament to be held in York, demands which have led some historians to conclude that the Pilgrimage was not motivated by religious but economic and political concerns. In January 1537, a separate rebellion broke out in Yorkshire under the leadership of local gentleman, Sir Francis Bigod. Bigod had been inspired by the recent rebellion, but unlike them, desired greater religious change. He was an evangelical, having been a scholar at Oxford University, although without taking a degree. Bigod was unable to garner much support among the populace, and his proposed siege of Hull was pre-empted when his forces were attacked outside of Beverely. He was executed at Tyburn on 2 June 1537. The Progress of 1541: Henry VIII’s progress in 1541 was largely a response to the northern unrest of the previous 5 years, as Shardlake explains on p. 17. In addition to the Pilgrimage of Grace, the ‘Wakefield Plot’ had recently been uncovered, in which gentry sympathetic to Catholicism intended to raise support in Pontefract for a rebellion against the crown. Historians have debated whether a proposed meeting with the Scottish King James V was also a motive for Henry’s progress. Barack and Shardlake notice the Scotch flag on p. 190 and speculate that Henry is awaiting Page 16 of 20 James’ arrival for a ‘meeting of kings’. Regardless of whether James V ever actually intended to meet with Henry at York, the defence of the north, both against the Scots, and from internal rebels and conspirators was a real concern. Political events in the capital in 1537 and 1540 had delayed Henry from undertaking the journey when initially proposed, but diplomatic events on the continent between the Holy Roman Empire and the French King, stimulated Henry into finally making the trip. Henry, half of his privy councillors (the other half were left in London to govern), his royal household, and an entourage of 4-5,000 horsemen (as well as various hangers-on), left London on 30 June 1541. With the prospect of meeting James at York in mind, Henry delayed in East Yorkshire, twice making unscheduled visits to Hull, before entering the city of York through Walmgate Bar on 16 September. Normally, royalty visiting the city entered through Micklegate, however, because the progress was coming from the east, rather than due south, their approach to the city was different. The king was met by the city officials at Fulford Cross which marked the south-eastern boundary of the city’s jurisdiction. There the mayor and aldermen made a submission to the king, begging forgiveness for previous transgressions, and presented the king with a gold cup containing £90 in gold coins, and a similar cup with £40 of the same to Catherine Howard. After waiting in vain for James to arrive for 9 days in York, Henry returned to Hampton Court on 24 October. Further Reading: Aylmer, G.E. and Reginald Cant, eds., A History of York Minster (1977). Clark, Peter and Paul Slack, eds., Crisis and Order in English Towns 1500-1700: Essays in urban history (1972) Crouch, David J.F., Piety, fraternity, and power: religious gilds in late medieval Yorkshire, 1389-1547 (2000). Dickens, A.G., ‘The Yorkshire Submissions to Henry VIII, 1541’, English Historical Review, 53:210 (Apr., 1938), 267-75. Dickens, A.G., The English Reformation (1964). Dyer, Alan, Decline and growth in English towns, 1400-1640 (1995). Galley, C., The Demography of Early Modern Towns: York in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1998). Guy, John, The Tudors: A Very Short Introduction (2001). Heal, Felicity, Reformation in Britain and Ireland (2003). Hoyle, Richard W. and J.B. Ramsdale, ‘The Royal Progress of 1541, the North of England, and Anglo-Scottish Relations, 1534-1542’, Northern History, 41:2 (2004), 239-65. Knowles, David, The Religious Orders in England, vol. 3, The Tudor Scene (3 vols., 1961). MacCulloch, Diarmaid, The later reformation in England, 1547-1603 (1990). Marshall, Peter, The Reformation: A Very Short Introduction (Forthcoming, Oct 2009). Palliser, David, Tudor York (1979). Sansom, Christopher J., ‘The Wakefield Conspiracy of 1541 and Henry VIII’s Progress to the North Reconsidered’, Northern History, 45:2 (Sep., 2008), 217-38. Tillott, P.M., ed., A History of Yorkshire: The City of York, in The Victoria History of the Counties of England, ed. R.B. Pugh (1961). Page 17 of 20 Tittler, R., The Reformation and the Towns in England: politics and political culture, c. 1540-1640 (1998). Primary Source Material: York City Archives, House Books State Papers, The National Archives; catalogued in Letters and Papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, ed. J. Gairdner, et al (1920) Printed Primary Sources: Hall, Edward, Hall’s chronicle; containing the history of England, during the reign of Henry the Fourth, and the succeeding monarchs, to the end of the reign of Henry the Eighth, in which are particularly described the manners and customs of those periods. Carefully collated with the editions of 1548 and 1550, ed. (1809). Royal Commission on Historical Monuments in England. An inventory of the historical monuments in the city of York, 1 : Eburacum, Roman York; 2 : The defences; 3 : South-west; 4 : Outside the city walls east of the Ouse. 4 vols.; vol. 1 edited by J.C. Ede (1962-1975) Pattison, Ian R. and Hugh Murray, Monuments in York Minster: an illustrated inventory (2000) The churchwardens’ accounts of St Michael, Spurriergate, York, 1518-1548, ed. C.C. Webb (1997). Valor ecclesiasticus temp. Henr. VIII: Auctoritate regia institutus. Printed by command of His Majesty King George III in pursuance of an address of the House of Commons of Great Britain, ed. John Caley, with an introduction and indexes by Joseph Hunter (6 vols., 1810-34). Giustiniani, Sebastian, Four years at the court of Henry VII: selection of despatches written by the Venetian ambassador, Sebastian Giustiniani and addressed to the signory of Venice, January 12th 1515, to July 26th 1519, trans. Rawdon Brown (2 vols., 1854). The Anglica Historia of Polydore Vergil, A.D. 1485-1537, ed. and trans. Denys Hay (1950). Yorkshire monasteries: suppression papers, ed. J.W. Clay (1912). Some notes on the main sources: House Books The City of York House Books are a selective record of the proceedings of the city’s council meetings. At these meetings, the mayor, aldermen, and council of Twenty-Four discussed the city’s most urgent business: where they managed the city’s finances; where merchants repaid their debts, and where craftsmen swore oaths. They regulated the city’s markets, made provisions for poor relief, maintained the physical aspects of the city, such as the walls and streets, and organised the city’s religious feasts and festivals, such as the Corpus Christi plays. Page 18 of 20 The House Books are not a verbatim account of the proceedings of the council meetings, but contains a record of the council’s most important business. The earliest surviving document in the House Books dates from 2 March 1474/5. The books were kept by the city’s clerk and contained formal documents such as bonds, recognizances, leases, copies of letters sent to and from the mayor and council, municipal laws and ordinances, appoint of civic officers and records of arbitration cases. The most frequent entry in the house Books were bonds to settle disputes by arbitration in front of the mayor and aldermen at the council chambers. Some guilds and religious houses also chose to make a record of their proceedings and charters in the city’s books. The House Books are valuable as a record of city life beginning in the late fifteenth century. York’s House Books are particularly noteworthy for the rich variety of their contents. Before the House Books, the York council kept Memorandum books, the earliest of which dates from 1377. Other sources for the early history of York include the Freemen’s Register, which is an annual record of all those granted the status of freeman in the city, the Chamberlains’ Account Rolls and Books, the Bridgemasters’ Accounts, and the records of the individual craft guilds. The House books tell us not only about local life, but they give us a local perspective on national and international events and an insight into wider social values. They provide an auxiliary record to those of the central government: to parliamentary decrees, royal proclamations, and other central records. Although York’s House Books are among the best in the country because of their variety, their value has not always been recognised. The books were held in the council chamber on Ouse Bridge until its demolition in 1738. The location of the council chambers so near to the river meant that the records suffered water damage. They were moved to the Guildhall, a place not much drier, where they were further damaged by flooding several more times before 1892. In addition to having been repeatedly subjected to damage from flooding, portions of the House Books are missing, likely a result of the fact that they were occasionally loaned out to the city’s legal officers. In 1957 the House Books were moved to the city library, and then to their present location in the city archives when they were moved into the same building as the art gallery in 1981. Letters and Papers and State Papers Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, ed. J.S. Brewer, J. Gairdner and R.H. Brodie (22 vols., London, 1862-1932) is a calendar, or series of short summaries, of documents relating to every aspect of the government of England, its outlying territories in the Irish Pale, Calais and Tournai, and its diplomatic relations with other European kingdoms and principalities, the Holy Roman Empire, and the papacy. The types of documents in Letters and Papers include private and official letters; reports; royal ordinances, instructions, proclamations, and orders; treaty papers; memoranda; council minutes; and drafts of parliamentary bills. Not all the official government papers from Henry VIII’s reign are in the State Papers at The National Archive (TNA), but some particularly from the later years of Henry VIII’s reign can be found in the Landowne, Harleian and Cotton Collections at the British Library (BL), and at Hatfield House, Hatfield, Hertfordshire (21 miles north of Central London). Page 19 of 20 The State Papers, which are the main archival collection relating to government under Henry VIII, are divided into 7 series; the main series is SP 1: Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, General Series, 1509-1547. These documents are bound into a series of volumes chronologically. Most of the documents are in English although some official papers were still written in Latin. Recently, a new digital project has made the state papers accessible to a broader audience. State Papers Online: Part I: The Tudors: Henry VIII to Elizabeth I, 1509-1603: State Papers Domestic is a searchable database of over 380,000 facsimile manuscript documents from TNA, the BL, and Hatfield House. Page 20 of 20