PART TWO - World Federation of Scientists

1

Thoughts on the Social Rate of Discount

Dr. Bruce Stram

Introduction

Two recent evaluations of potential global warming policy are starkly at odds. The “Stern

Review” (Nickolas Stern for the British Treasury) and “A Question of Balance” (William

Nordhaus) are nearly an order of magnitude apart on what level of current resources should be directed toward reducing carbon emissions. This difference is all the more striking because careful examination of the two documents reveals that both use very similar estimates of future damages from warming. The difference almost entirely boils down to one number: the rate of discount applied to those future damages. Nordhaus uses a discount rate comparable to that used for most benefit cost analyses which are based on market rates of return. Stern uses a very low rate, a choice driven by the fact that this analysis is intergenerational in nature, which per Stern requires a very low discount rate to avoid generational bias.

Social rate of discount has been a theoretical issue for economists for many years, beginning at least with Ramsey (1928). Its application circumscribes many important policy issues associated with economic evaluation of long term consequences versus actions that might be taken today. Unquestionably, however, the dialogue regarding global warming has given substantial new impetus to the discussion.

Much of the dispute about the “social rate of discount” centers on the fear that the current generation will be selfish with regard to preventing future damage to the environment, consuming now and leaving great costs for future generations. And this despite the fact that a market like rate of discount applied to both private and public cost benefit analysis encourages deferral of current consumption in favor of investment and provision for the future.

Models optimizing long term economic and environmental consequences of human activity seem to yield, at least for some observers, acceptance of too much environmental harm. Since market based rates of discount seem to reduce the present value of dire environmental consequences to very low values over very long time periods, such observers logically question whether this discounting applied to time periods extending well beyond current generations has inherent flaws. The hypothesis here is that such flaws, if they exist, are occasioned by more mundane shortcomings in the valuations placed on environmental damage in the future.

Discounting Costs and Benefits

Cost benefit analysis (CBA, public sector) or discounted cash flow (private sector) follows the same general methodology. Values with occur in the future are factored by a compounded discount rate which resembles a rate of interest (i.e. 1.06). These discounted values are then compared to current values.

The basic rationale for such discounting is that economic resources which are withheld from current consumption can be diverted to projects or activities which on average provide for greater future benefit. Such “diversions” include investments in physical capital, research and development of technology, and education.

Economists point to the markets for savings and lending to provide guidelines for establishing criteria for selecting desirable investments. These markets in effect aggregate willingness to defer consumption versus receiving future reward. Investments which do not yield returns at least equal to these rates diminish overall welfare (for public investments) or reduce the value of a private sector business or activity. Both governments and businesses borrow funds which are repaid with interest (i.e. a discount rate). Businesses also raise equity capital for projects with the expectation that there will be a positive return, also an implicit discount rate.

Earning a positive return on invested capital is part of an amazing and highly distinct period of economic development in relatively recent history.

2

“Was Malthus Right? Economic Growth and Population Dynamics, Jesus Fernadez-

Villaverde, University of Pennsylvania, Dec. 1, 2001

3

Economists strongly believe that the notion of a focus on capital formation and the concomitant formalization of a market for capital is an integral part of the foundation of this economic growth. This development, along with entrepreneurship, vision, risk taking, and

“animal spirits” has created an engine of economic growth. CBA and discounted cash flow is a methodology that is a codification of this process in order to provide criterion for efficient investment. This methodology is used almost universally for evaluating governmental and business investments.

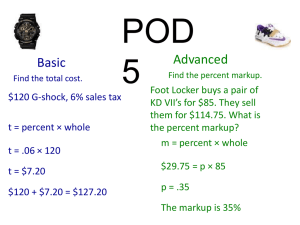

Objections have arisen, however, regarding very long term evaluations. It begins simply as a matter of arithmetic. Typically a discount rate is estimated in the range of 4% to 6% in real terms. Thus a project “paying off” in 10 years must retrun 1.8 times its cost. Alternately, an asset valued at 1.8 10 years from now would be valued at 1 today.

Longer term compounding has a much more dramatic effect. Firty years from now, something valued at 18 would be deemed to be worth 1 today. For 100 years the ratio to current value would be 340:1, and for 200 years, an astonishing 115,000:1.

Needless to say, applying such discounts to the value of hypothesized adverse effects from global warming (or other environmental damages) is viewed with some substantial concern.

That has led to a vigorous renewal of the social rate of discount analysis.

A Brief Examination of Social Rate of Discount Theory

Much thought has been devoted to this fundamental issue of weighing the value of the future to value in the present. These include the following: The Stern approach; various rationales for declining discount rates (over time, DDR), and a “Fat Tails” approach. These will be outlined in turn, followed by an alternative approach.

Stern

The Stern Report justifies the use of a very low (relative to a typical 4.5% to 6% real often used for cost benefit analysis (CBA)), numerically 1.4%. The rationale is based on moral grounds. It devolves from a well known mathematical and highly theoretical economic model depicting economic growth based on capital formation and population growth and optimization of welfare over tiime. An end result is a simple formula: r = ρ +θg=δ the letter r represents the marginal rate of return to capital, ρ “the pure rate of time preference, i.e. human’s preference for gratification now as opposed to the future, θ is the elasticity of utility (or welfare) with respect to income, g per capita incom e growth, and δ the social rate of discount.

This may be interpreted as follow: societies’ future welfare should be discounted according to the marginal rate of return to capital (r and δ being equal), and in addition by decline in the value of future income increase fostered by growth in per capita income. (Given the abstract nature of the analysis, many real world conditions (taxes, externalities, etc) that would disturb the equality are ignored.)

From this foundation, the Stern Report makes the following assertion: the pure rate of time preference observed for the current generation should not be visited on future generations to their disadvantage. Therefore that component of the formulation should be set to zero. Since it is take to be 3%, the social discount rate is appropriately 1.4% rather than say 4.5% which would represent the marginal return to capital.

4

In this, the Stern Report follows a number of eminent British (and other) economists —

Ramsey, Harrod, etc.

However, this formulation would have the current generation defer consumption to achieve much greater benefit for future generations than would be the case applying the standard methods. Such an approach seems to ignore the fact that a high discount rate implies continued economic growth such as has occurred over the last few hundred years. Thus those future generations for whom greater sacrifice is deemed appropriate will be much wealthier than we currently. Equivalently, this is akin to asking that our ancestors alive in

1800, and much poorer than we today, be compelled to reduce consumption in order to additionally benefit us. By this formulation, future generations are to be treated better than we have been by our ancestors, and better that we treat ourselves.

Uncertainty as to Future Growth Rates

It is certainly the case that for at least the last two hundred years, “Western” economies have enjoyed historically very high growth rates driven in significant part by a high marginal productivity of capital. Much of the rest of the world (weighted by population) seems finally to be catching on and achieving this by similar means. But this growth is not axiomatic. There is no certainty this effect will continue in the future, and the less so the farther off the future.

Such uncertainty has given rise to several analyses which seem to imply that use of DDR is appropriate.

Financial markets are often looked to find measures that reflect a rate of return to capital and hence a CBA discount rate. But forward markets, which are not perfect predictors of the future, do not extend to the future being contemplated in very long term analyses and therefore provide very limited guidance.

Martin Weitman tries to capture this effect roughly as follows: he defines future states of the world which embody different returns to capital and hence appropriate discount rates. He then proposes to evaluate the future in total by summing these weighted by their probability and discounted by their own return to capital. As time goes to infinity, the future world with the “smallest possible” discount rate dominates the weighted average.

This hoisting of high discount rates on their own petard certainly deserves a smile. However, some objections come immediately to mind. What is the smallest possible discount rate, zero? Certainly this and even negative discount rates are contemplated in the literature on this subject. An infinite time horizon makes no sense. If nothing else, the earth and the universe have a limited life. And finally there is a certain circularity to the result: if the conclusion of the analysis is that the “lowest possible” discount rate is the one appropriate, shouldn’t it be applied to all the future states, obviating the conclusion?

But these objections don’t apply to a more mundane point. Given uncertainty as to potential future growth rates and hence appropriate discount rates, a normal probability distribution of such would suggest that an expected value is a reasonable measure to use for determining expected future income. However, the marginal value of that income will be higher in lower growth situations then higher. That is, even if uncertain future income is normally distributed, future welfare is not. Further, one can demonstrate that there is a DDR which captures the welfare effect of this asymmetry. (Whether using a DDR to reflect this is the best practice is another matter and will be considered below.)

We itzman also raises a “Fat Tails” argument. The supposition is that the probability of a catastrophic outcome, i.e. representing near infinite loss from global warming remains high enough so as to more than offset cumulative exponential discounting. This really amounts to a strong suggestion that cost benefit analysis cannot be reasonably applied to global warming concerns given potential catastrophic impacts. But a resource allocation problem remains: there are many unknowable probability catastrophic events (meteor, hadron collider creating a black hole on earth, nano technology gone wild, etc.), But only finite resources are available now to be allocated toward avoiding possible infinite outcomes in the future.

Perhaps a more useful approach to such concerns is to these dangers in terms of

“backstops”. That is, instead of evaluating the consequences of the hypothesized events, examine the actions that might be taken to avert them. For global warming these might include the cost of chemical carbon capture and storage, genetic engineering of carbon eating and sequesting plants (Dyson) and/or geoengineering. CBA is clearly appropriate for evaluating such alternatives.

Substitutability

CBA or discounting makes sense because the flow of reproducible or manufactured goods can be increased by deferral of consumption and comcommitant capital formation. But environmental assets are not generally reproducible. That natural endowment can be and demonstrably is being reduced by human activity. If it is reasonable to suppose that future generations will benefit from high economic growth rates (with appropriate high discount rates), the availability of environmental assets will diminish both in a relative sense and absolutely. Therefore, the value of such assets will logically increase relative to reproducible goods. Further, one may readily observe that richer societies spend a greater proportion of income on environmental protection and the enjoyment of such amenities. One can posit that as environmental assets diminish and reproducible goods increase, that an increase in value of the former could outweigh the growth rate of the latter, and even be greater than the discount rate. Such circumstances potentially provide for an additional offset for the discount of potential environmental damages in the distant future. (Krutilla and Fisher)

Conclusion

No one believes that economic analysis of the far off future necessary to evaluate the potential dangers of global warming (or any other very long term situations) is anything but problematic. Straightforward use of a “standard” discount rate yields a devaluation of future environmental damages which is disturbing to many. That has led to much reevaluation of standard CBA methods and in particular, analysis of the appropriate social rate of discount.

Various methods have been proposed to revise this rate to reflect various concerns. These have been briefly considered in this paper and are certainly in whole, worthy of consideration.

However, there is no inherent need to incorporate such adjustments in a singular discount rate number. At best, doing so is simply an analytical convenience. Each of the adjustments considered here could be incorporated into an overall analysis as a separate item in an overall analysis.

Such an approach would be eminently more functional than relying on a single discount rate factor. The logical need for such adjustments remains open to question. Further in

5

6 application, the elements of these adjustments are themselves highly uncertain. For example the long term decline of the marginal utility of income at much higher per capita income levels is highly speculative. So too is any uncertainty in long term rate of economic growth and the return to capital. Including any such adjustments explicitly rather than subsuming them into a single discount rate provides for much more clarity and transparency.

This analysis very strongly implies that collaborative action between environmental scientists and economis to get more correct answers resulting from more careful examination of potential future income levels, their impact on environmental amenities and systematic estimation of how the valuation of environmental benefits changes with income level.

References

Gollier & Koundouri & Pantelidis, 2008. " Declining discount rates: Economic justifications and implications for long-run policy ," Economic Policy , CEPR & CES &

MSH, vol. 23, pages 757-795, October

Krutilla, J. and A. C. Fisher (1975), The Economics of Natural Environments. Baltimore:

Johns

Hopkins University Press.

Nordhaus, William, A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming

Policies, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2008

Ramsey, F. P. (1928), New Haven, CT, 2008s on Global Warming Policies,long-run policy

Stern, N.H. (2006). ‘The Economics of Climate Change’, available at: http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/independent_reviews/stern_review_economics_climate_ change/stern_review_report.cfm

Weitzman, M. (1994), cfmrt.cfmindependent_reviews/stern_revieJournal Environmental

Economics and Management 26(1), 200ent 2

Weitzman, M. (1998), Economicsndependent_reviews/stern_review_economics_climate_ol

Possible Rate(19Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 36, 201al of

Weitzman, M. (1999), tal Economics and Managemenbut. . .

’ . in P. Portney and J. Weyant

(eds),

Discounting and Intergenerational Equity, (pp. 23ng and Intergenerational Equityanageme

Future.

Weitzman, M. (2001), generational EquityanAmerican Economic Review 91(1), 261 Econ

Weitzman, M. L. (2004), Statistical Discounting of an Uncertain Distant Future, mimeo,

Harvard University.