The Rejection of Hedonism, Power-Seeking and Injustice Plato

advertisement

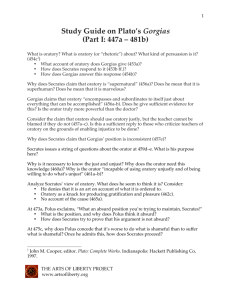

The Rejection of Hedonism, Power-Seeking and Injustice Plato takes very seriously the claim that pleasure or power or immorality can serve our self-interest. In both the Gorgias and the Republic Socrates is confronted with these views and he responds to the challenge very carefully. The Rejection of Power-Seeking – The first two speakers in the Gorgias are the sophists Gorgias and Polus who present the view that rhetoric (public speaking) and sophistry are the tools by which we can obtain power and so live the best life. This seems today, as then, a plausible claim – if you have the skills necessary to persuade people (your family, your partner, your work colleagues, the general public) that what you are saying is true, even if it isn’t, then you should be in a strong position to get whatever you want. The cynicism that people often have about politics is grounded in the suspicion that politicians are skilled in sophistry, but that their messages are empty. Socrates rejects the claim that sophistry (i.e. the verbal skills of persuasion) brings us any real power. Even though such a skill appears to benefit us, this is just an illusion and the power is illusory. To Socrates sophistry is a form of ‘pandering’, in other words gratifying other people without any thought as to whether the satisfaction is a good thing or not. Taking Socrates point forward we can question our own political spin-doctors by asking ‘who has the real power: the politician or the people they are so desperately trying to please?’ Aristotle makes a similar point in the Ethics when he says that winning the respect of others cannot be the key to living a good life. This is because he believes that the best possible life is not one which depends on the opinions of others; it should be self-sufficient. a) List as many advantages as you can of power-seeking b) List as many disadvantages as you can of power-seeking c) Do you think the skills of rhetoric and public speaking really bring us power? Why/Why not? d) Do you agree with Aristotle that it is not a good thing to depend on the opinions of others? Why/Why not? The Rejection of Hedonism – Midway through the Gorgias a new character, Callicles, steps into the debate. He is a person who is prepared to push the debate about power and self interest much further than is socially acceptable. He is dismissive of the constraints placed on people by ‘social’ morality (e.g. by the kinds of rules that people agree to under a Hobbesian contract). He thinks that morality, or justice, is a way of keeping strong men down, and that only the truly strong will throw off the shackles of morality and do whatever they need to do, however immoral, in order to satisfy their needs and wants. For Callicles the best kind of life is one in which we get as much pleasure as we can. CalliCles: “i tell you frankly that the man who is going to live as a man ought, should encourage his appetites to be as strong as possible and be 1 able by means of his courage and intelligence to satisfy them in all their intensity by providing them with whatever they happen to desire” Gorgias 491-2 Callicles’ claim that pleasure is the ultimate good is known as HEDONISM. Socrates undermines the hedonist position in a number of different ways. He asks us to consider the lives of two men, one who can control his desires and another who indulges all his desires. He uses the analogy of two people, each of whom has a number of storage jars. The first person has sound and full jars – once he has filled them up he gives them no more thought. The second person has leaky jars and has to fill them up day and night. The question is which life is happier: the life of someone who can control their desires, or the life of someone who is constantly having to satisfy them (the hedonist)? For Plato the answer is clear. The hedonist lives a life of constant craving, every desire that is satisfied is followed by a new desire that demands satisfaction. Those people who can control their desires (temperate people) are happier than those who can’t, (the intemperate hedonists). Aristotle attacks hedonism on the grounds that humans have the potential for more than just satisfying our physical desires, and this is what distinguishes our lives from those of other animals. Even Callicles, who puts forward an extreme form of hedonism, is forced to admit that not all pleasures are good. Socrates suggests to Callicles that the pleasures of running away from battle are not good pleasures. Callicles, like many ancient Greeks, believes that cowards are a disgrace and so has to agree with Socrates. Socrates then takes the point further and asks Callicles whether someone who gets pleasure for itching and scratching and spends all their life satisfying their desire to itch and scratch is living a happy life. Eventually Socrates forces Callicles to withdraw from his extreme hedonist position and acknowledge that what we are really seeking is not pleasure, but whatever is good. a) Do you think it is possible that there is a way in which a hedonist society could work? Why/Why not? b) Is it possible to live without ever having hedonistic motives? Why/Why not? The Rejection of Injustice – In Plato’s Republic he uses the character of Thracymachus, another sophist, to the ultimate challenge to Socrates: Thracymachus: “when a man suCCeeds in robbing the whole body of Citizens and reducing them to slaves they call him happy (eudaimon) and fortunate. So we see that injustice, given scope, has greater strength and freedom and power than justice. Injustice is in the interest and profit of oneself” Thracymachus is proposing that our real self-interest is served by ignoring the moral rules laid down by society and doing whatever it takes to get what we want. Those we are able to do this most successfully are the ones who live the best lives. This rather extreme position is put forward by both Callicles and Thracymachus, and they express unhealthy admiration for those bloodthirsty and ruthless tyrants who are able to ignore the moral rules of society to achieve their goals. But there is 2 a moderate, and commonly held version of their ‘immoralist’ position which Plato treats carefully: that it is in our interests to do whatever we like to get what we want, so long as we appear to behave morally and we aren’t caught. As Socrates points out, the question of whether we should live moral or immoral lives is fundamental, affecting our whole way of life. According to both Plato and Aristotle people are often mistaken about what is really the best life to lead, what is in our true self-interests: we can be wrong both about the ends (what we should be aiming for) and the means (the methods by which we get there). a) What advantages are there for only appearing to behave morally but actually acting out of our own self-interest? b) To what extent to you think (as Plato and Aristotle say) that we are mistaken about what is really the best life to lead? Why do you think we are mistaken in such a way? 3