Linguistic Society of America

advertisement

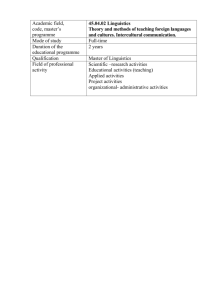

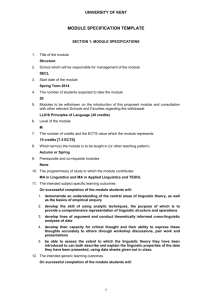

Ninetieth Anniversary of the Linguistic Society of America: A Commemorative Symposium Saturday afternoon session, January 4, 2014 The LSA Linguistic Institutes Julia S. Falk La Jolla, California jsfalk@san.rr.com Surveys over the years have revealed that the members of the Linguistic Society of America consider the Linguistic Institutes to be the Society’s most important service to the profession, second only to the publication of Language (Linguistic Society of America Bulletin [hereafter Bul] 119, p. 3, 1988). Those who have participated know firsthand the spirit that makes Institutes so engaging and so warmly remembered. In Spring 1927, Reinhold Saleski – Professor of German at Bethany College in West Virginia – wrote to Roland Kent, Secretary of the Linguistic Society of America. Saleski proposed a Linguistic Institute for the summer of 1928. This “gathering of scholars for interchange of ideas” (Bul 2, p. 3, 1928) was modeled on the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, a summer program for research biologists under development at that time by the National Academy of Sciences (www.whoi.edu/main/history-legacy). Woods Hole had $2,500,000 in funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. The LSA budget balance was $799.36. It is not surprising that the Executive Committee was hesitant to embark on such a project. But Edgar Sturtevant was far from hesitant. Professor of Linguistics and Comparative Philology at Yale University, Sturtevant took up the idea and molded it into something very like the Linguistic Institutes we still have today. He broadened the scope to include both the “gathering of scholars” and the offering of course work. He gained a commitment from his university to provide facilities and to permit those who held the Ph.D. to attend at no charge. He developed a list of courses and promised 21 colleagues a teaching stipend of at least $250 each. And he successfully petitioned the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) for $2,500 in support of these faculty salaries. E. H. Sturtevant With these preparations and support in place, the LSA’s Executive Committee, at the annual meeting in December 1927, approved “the project of a Linguistic Institute” and appointed an administration committee composed of Sturtevant, Director; Saleski, Assistant Director, and Kent. The approval extended to a second Institute for summer 1929 – “Provided always, that the Linguistic Society incur no financial obligation therein” (Bul 2, p. 6, 1928). The first Institute ran at Yale for six weeks during the summer of 1928. There were 24 faculty and 43 students, with some overlap as faculty members chose to take or audit courses given by their colleagues. Nearly 80% of the faculty came from universities other than the host institution. Of the 31 courses taught, the most heavily enrolled was “Introduction to Linguistic Science” with 7 students (taught by Eduard Prokosch of NYU). Also popular were “Gothic and Comparative Germanic Philology” with 6 students (Hermann Collitz of Johns Hopkins University, the first LSA president), and – with 5 students each --“Greek Dialects” (George Melville Bolling, The Ohio State University, the editor of Language) and “Old Latin and Its Development into Classical Latin” (Roland Kent, University of Pennsylvania, LSA Secretary/Treasurer) (Bul 2, 1928). The predominance of historical courses at this and other early Institutes reflected the interests of the majority of LSA members at that time. But Sturtevant was determined to introduce the latest advances in the field. The first Institute included courses in “American English” (Louise Pound, University of Nebraska), “Experimental Phonetics” (Oscar Russell, Yale) and “Methods of Studying Unrecorded Languages” (John Mason, University of Pennsylvania). At the second Yale Institute, the first fellowships were awarded. Two graduate students each received $100 – enough to cover the registration fee ($20), tuition ($55), and dormitory accommodations ($4 per week). Another precedent set at that second Institute was the holding of a concurrent conference – the “Conference on the Proposed Linguistic Atlas of the United States and Canada.” 50 scholars gathered for the presentation of papers and discussion. Integrated with the Institute, there were courses and public lectures on dialects, dialect geography, and the latest technology for the mechanical recording of speech. Over the years, conferences and workshops at the Institutes have been the source of new directions for the field, for example, psycholinguistics in 1952, sociolinguistics in 1964. Focus on a particular topic became common in later Institutes, and, in the mid 1980s, Institute themes became the norm. It must be acknowledged that some themes have been so broad that virtually any linguistic subject could be included in their scope. It would be difficult to overstate the importance of the Institutes in the history of American linguistics. The Atlas project emphasized the analysis of contemporary language, a focus on speech, and the necessity of working directly with speakers (at that time called “informants”). These same principles applied to the study of native American languages. In both cases, new methods of collecting, recording, and analyzing data were essential, and these became a primary concern in the descriptivist tradition that dominated American work for the next quarter century. Sturtevant directed the first four Institutes --- 1928 and 1929 at Yale, then 1930 and 1931 at the City College of New York. Expecting a long future, he established an Endowment Fund for the Institutes and had raised $1,873 by the end of the 1931 session. However, now at the height of the Great Depression, the meager salaries deterred faculty, and neither funding agencies nor universities offered support for another Institute. And so there was a four-year hiatus. In 1935, Sturtevant and Kent met with Charles Fries. Fries was a Foundation Member of the LSA and Professor of English at the University of Michigan. These men created an Institute for 1936 that was an integral part of the University of Michigan Summer School. The LSA preferred some independence for Institutes, and unlike earlier and later Institutes, the staff was made up almost entirely of local faculty, who taught 21 of the 27 courses offered. The LSA was so concerned about this imbalance that it contributed $265 to fund outside lecturers. The next summer, the LSA gave $170 for the same purpose. When the Executive Committee approved a 1938 Institute, it again declared that “the Society assume no financial responsibility” (Bul 10, p. 11, 1937). This turned out to be wishful thinking. Host universities continued to provide the facilities, up to half of the faculty, and most of the finances. But each year the LSA funded many of the visiting speakers, as well as those faculty who came to be called “Institute Professors.” Charles Carpenter Fries From the revival that began in 1936, Michigan was the home of Linguistic Institutes on 18 occasions over the next 30 years. Linguists found Michigan to be an excellent host. Salaries were satisfactory, tuition was low, and attendance increased (Sturtevant 1940, p. 85). The quality of the linguistics holdings of the University Library, the Midwest location, and the usually pleasant summer weather were all factors cited in a survey of Institute participants (Report of the Special Committee 1940). And in one case where a Michigan tradition was troublesome, it was simply ignored. 1946 LSA President E. Adelaide Hahn walked without hesitation up the steps and “through the previously exclusively-male front door of the Michigan Union” (Hill 1963, p. 26). Front Steps of the Michigan Union E. Adelaide Hahn Then and now, there is special value in the cordial and collegial atmosphere of the Institutes, with their gatherings of scholars and students from around the country and, in recent times, around the world. This was most important during the early decades when there were few departments of linguistics at American universities. Linguists held appointments and students studied in language, literature, or anthropology departments where, someone said at the time, “they find no one who understands or cares about” linguistics (Report of the Special Committee 1940, p. 93), a situation that some of our colleagues still encounter. Through Fries’ initiative, the Society began a summer meeting at the site of the Institute in 1938. These meetings brought even more people together and “proved vigorously stimulating” according to Professor Fries (Bul 12, p. 19, 1939). They also provided excellent socializing. While annual meetings in the winter had cocktail parties and, these days, cash bars, Institutes and summer meetings celebrate with barbecues, picnics, pizza parties, and beer gardens. The more of these events there are, the more fondly an Institute is remembered. And with good cause. Frequent informal gatherings result in new friendships and a widelyexpanded professional network for those who attend. During the 1930s, the ACLS funded field work on approximately 80 native American languages. Linguists seeking to learn more about these languages and the methods of studying them, came to the Institutes at Michigan. In 1937 Edward Sapir taught “Field Methods in Linguistics” and “an informal course on the phonetics of Navajo.” In 1938, at Sapir’s suggestion, a speaker of Hidatsa came to the Institute and worked publicly with Carl Voegelin and Zellig Harris. Leonard Bloomfield worked with a speaker of Chippewa. Bloomfield also taught the “Introduction to Linguistic Science” that year, a course “which was attended by virtually the entire membership of the Institute,” over 200 people (Sturtevant 1940, p. 87). The advent of World War II initiated a concern with the modern languages that could prove useful to the American government during and after the war. The ACLS funded an Intensive Language Program, under the direction of J Milton Cowan, who happened to be LSA Secretary/Treasurer. That program reach more than 700 students at 18 institutions and involved 26 languages (Language 18, p. 255, 1942). It directly affected the Institutes. Modern language courses now became part of Institute offerings and were meant to serve as demonstrations of the new “intensive method.” An assistant professor of German reported taking a course in Thai “in order to get familiar with the method of teaching unusual languages by using a native informant as assistant in classroom work” (Bul 17, p. 13, 1944). The Michigan Institutes of the 1940s became known for work in applied – or practical – domains. For many years, these Institutes were closely related to a group known today as SIL. Originally called Camp Wycliffe, this was a summer program for the training of missionaries, including linguistic work to prepare its students for developing writing systems and bible translations in the field. In 1942, the program was formally renamed the Summer Institute of Linguistics; its president was Kenneth Pike. It is not surprising that there was occasional confusion between this Summer Institute of Linguistics and the LSA’s summer Linguistic Institute. The two organizations were distinct in goals, functions, and affiliations, but there was overlap in membership. Pike had studied at the Linguistic Institutes with Sapir and Bloomfield and earned his doctorate from the University of Michigan under Fries in 1941. He attended the Linguistic Institutes nearly every year they were at Michigan, sometimes to teach a course or two, sometimes to give a lecture, and often to demonstrate his “Monolingual Approach to a Language Unknown to the Linguist” (e.g. at the 1946 Linguistic Institute (Bul 20, p. 12, 1947)). A stranger speaking a language unknown to Pike would come to the front of the room, and Pike – using a handful of simple props (perhaps some leaves, a piece of fruit, a stone) and working without an interpreter – would in less than an hour elicit examples of the stranger’s language, write them on blackboards in phonetic transcription, analyze aspects of the phonological and grammatical systems represented in the data, and even speak a few phrases in the language. Monolingual Demonstration In some years during the 1940s, Pike, his colleagues, and students from SIL came close to dominating the LSA summer meetings. For example, in 1946 more than a third of the papers were given by SIL faculty and students (Bul 20, pp. 3-4, 1947). LSA members at the 1947 summer meeting passed a special resolution commending the work of the SIL “as one of the most promising developments in applied linguistics in this country” (Bul 21, p. 4, 1948). At the same time, it is important to note that Pike, in phonetics and phonology, and Eugene Nida, in morphology and syntax, were teaching core areas of linguistics at the Linguistic Institutes. During the 1940s, the ACLS continued as the chief external funding source for the Institutes, but it “did not find it possible to make a contribution to the budget of the Institute of 1949” (Bul 23, p. 18, 1950). The same year, the LSA and the University of Michigan had concluded an agreement that the University would hold an indefinite number of sessions of the Linguistic Institute (Bul 22, p. 11, 1949). The withdrawal of ACLS support led the University to withdraw from this agreement. The 1951 Institute was held at the University of California at Berkeley. Michigan’s hold on the Institutes was broken. For the next 30 years, they took place at 18 different universities, broadening the scope of offerings and expanding the participant base. A short-lived policy begun in 1952 and concluded in 1969 placed two consecutive Institutes at any university that had not previously hosted. (See the list of Institutes and their Directors on the LSA website at www.linguisticsociety.org.) For more than 50 years, Institutes and summer meetings were held annually. Each Institute took place over a period of six to eight weeks, beginning in June and ending in August. Summer LSA meetings were scheduled for the last weekend in July or the first weekend in August. The ACLS provided student scholarships that covered tuition and dormitory fees. Holders of the Ph.D. were warmly welcomed to the “gathering of scholars” and given access to courses without payment of fees. The LSA used income from the Linguistic Institute’s endowment fund to provide stipends to visiting faculty who offered evening lectures open to the public. These evolved into what today are called the Forum Lectures. Institutes in 1954 and 1955 were anomalous. Each year had three simultaneous Institutes, at Georgetown University, the University of Chicago, and the University of Michigan. Basic courses were conducted at all three, but it was intended by the Executive Committee that “advanced courses should take special advantage” of local personnel and facilities (Bul 27, p. 12, 1954). The experiment was never repeated, and one of the reasons was articulated quite clearly by the Director of the session held at Michigan in 1955, who referred to “the problem of two competing Institutes” and the complications of co-operation with the other directors (Bul 29, p. 17, 1956). Programs were normally announced in an issue of the LSA Bulletin, with lists of faculty and courses to be offered. And at the annual meeting of the Society following an Institute the Director would present a detailed report on staffing, enrollment in courses, and attendance at lectures. This too was published in the Bulletin so that all members of the Society might be fully informed about the Institutes. The regular availability of so much detailed information about the Institutes was almost certainly responsible for the wide support they enjoyed over the years. Some comments from Institute Directors in their final reports reveal how slowly the field was changing. For example, it was not until 1949, 21 years after the first Institute, that a Director could say: “One had the feeling that the structuralists and the historical linguists are getting to understand each other better” (Bul 23, p.17, 1950). A later director declared: “[we] should consider the possibility of an increased emphasis on historical and comparative linguistics” (Bul 31, p. 16, 1958). The statement occurred in the final report for the Institute in 1957, the year Noam Chomsky’s Syntactic Structures was published. Institutes have not always been on the cutting edge of the field. In the official records of the Institutes, it was not until 1960 that there was even a hint of acknowledgement of the arrival of generative grammar. Martin Joos organized “a small advanced seminar, open only by invitation, on problems in syntax,” undoubtedly designed to meet the challenges posed by Chomsky’s work (Bul 34, p. 23, 1961). The “invitation only” was so contrary to the strong tradition of openness at the Institutes that a number of questions could be raised. Unfortunately, I have found no further information in the public records. We do know that the following year, 1961, for the first time “A special feature of the summer was a full course on transformational analysis” (Bul 35, p. 22, 1962). This was also the year for which MIT had petitioned to conduct an Institute (Bul 33, p. 15, 1960), a year prior to its role as cohost, with Harvard, of the 9th International Congress of Linguists in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The LSA Executive Committee refused MIT’s petition for a Linguistic Institute in favor of the University of Texas. From the beginning, the Linguistic Institutes have been run by committees – the Committee on the Administration of the Institute, the Committee on the Place of the Institute, the Committee on the Future of the Linguistic Institute, the Committee on Specifications for Future Institutes, and numerous ad hoc committees on finances and funding. The most important has always been the Administrative Committee. Its primary members are the Director, generally the faculty member who has persuaded his or her university to offer to host the Institute, and the Associate Director, often someone who had prior experience with an Institute and could offer continuity and enthusiasm. The precedent was set by Edgar Sturtevant, who served as Director and then Associate Director for almost every Institute until his death in 1952. Ivan Sag was the modern successor to Sturtevant, serving as organizer, codirector, associate director, and “informal guru” at many Institutes from the mid-1970s until his death in 2013 (letter from Institute Directors 1986-2013 to Colleagues dated October 24, 2013). The role and number of Institute Committees declined with the establishment of a professional Secretariat in 1969. Members of the Society lost much of their direct contact with the Institutes as the Secretariat assumed administrative duties in soliciting proposals from universities, establishing a screening process for fellowship and scholarship applications, and printing announcements for the Institutes. While the Secretariat did standardize search and selection procedures for the Institutes, the named Chairs, and the students awarded fellowships, it was also responsible for a reduction in access to information about enrollments and attendance when the Directors’ final reports moved from the printed Bulletin sent to all members, to placement on-line, and finally to the Annual Meeting Handbooks, available only to members attending those meetings. Funding for fellowships and scholarships at the Institutes came from foundations working through the ACLS. Most notably in the late 1950s and the 1960s, the Ford Foundation provided Institute funding of approximately $25,000 to $30,000 per year, not only for student aid but also for direct institutional subsidies (Bul 32, p. 23, 1959). Then, with the launch of the Russian satellite Sputnik in 1957, the federal government began to fund the study of linguistics, as well. The National Science Foundation provided almost $5,000 for the 1957 Linguistic Institute (Bul 31, p. 15, 1958). And the Congress of the United States quickly responded to the challenge of Soviet science by passing the National Defense Education Act in 1958, which included fellowship funds for students attending the Linguistic Institutes. At the 1964 Institute, 231 students received financial support from 22 sponsoring organizations, including government agencies (Bul 38, pp. 31-32, 1965). The most prestigious fellowship at the Institutes is the Bloch Fellowship. Originating from the Julia Bloch Memorial Fund, established in 1960 (Bul 34, p. 18, 1961), the fund became the Bernard and Julia Bloch Memorial Fund in 1965, following Bernard Bloch’s death (Bul 39, p. 20, 1966). Julia was never a registered member of the LSA, but she played a measurable role in American linguistics for nearly 30 years, first as co-author of several volumes in the Linguistic Atlas of New England in the 1930s, later working with the journal Language after Bernard became editor in 1940, and often present at the summer meetings of the LSA at the Institutes. Her contributions and her memory have become obscured by the Society’s practice of referring to “the Bloch Fellowship”. It is often assumed that this refers solely to Bernard Bloch. First awarded for the 1970 Linguistic Institute (Bul 43, p. 15, 1970), the Bloch Fellow receives a generous stipend covering the costs of attending an Institute. In addition, since 1980, the Bloch Fellow has represented students in the LSA as a full voting member of the Executive Committee. The second named fellowship at the Institutes also came from a memorial fund – the James McCawley Fellowship, established in 1999 following the death Jim McCawley, the Andrew MacLeish Distinguished Service Professor of Linguistics and East Asian Languages at the University of Chicago. Currently, the Society is raising funds for a third memorial fellowship -honoring Ivan Sag. The first Institute Professorship was created in a bequest in 1944 by Klara Hechtenberg Collitz. She held a Ph.D. in Comparative Philology, as did her husband Hermann Collitz. He died in 1935. She maintained her LSA membership until her death in 1944 and she left most of their estate to the Linguistic Society for the establishment of a professorship which she instructed be named “The Hermann and Klara H. Collitz Professorship for Comparative Philology”. The Society promptly overlooked Klara when it reported that, at the 1948 Institute, Edgar Sturtevant held the first “Hermann Collitz Professorship” (Bul 38, p. 21, 1965). As with the Bloch Fellowship, references to the “Collitz Professorship” continued to lead those aware only of our first president to conclude that the professorship honors him alone (e.g., the 1978 Linguistic Institute Report: “The Herman[sic] Collitz Professorship was held by …” Bul 81 p. 19). It was not until the 1990s when Sarah Thomason and I brought the full, bequeathed title to the attention of the Secretariat and the Executive Committee there was awareness of the inequity. The full title now appears on the Society’s webpage (www.linguisticsociety.org/meetingsinstitutes/institutes/named-professorships). However, the shorthand references to “Collitz Professor” and “Collitz Professorship” continue (ibid.) The Institute’s Endowment Fund grew substantially over the years, enhanced by contributions, bequests, and, beginning in 1975, revenues from the fees visiting Ph.D. scholars began to pay. In 1971, the last year in which it was reported separately from the Society’s other endowment monies, the Linguistic Institute Endowment Fund had a balance of $51,346 (Bul 52, p.11, 1972). In 1961, the balance was $38,608.59, compared to the LSA’s endowment fund of just $6,848.50 (Bul 35 p. 13, 1962) At this point, the Society committed to a second Institute professorship (Bul 34, p. 18, 1961). W. Sidney Allen of Cambridge University was the person chosen as the first LSA Professor (Bul 35, p. 20, 1962). Effective in 1986, the name was changed to the Edward Sapir Professorship. This would seem an odd choice for the Institute’s second named Professorship. Sapir had little to do with the Institutes. He was not involved in their creation. He had declined Sturtevant’s invitation to teach “any course or courses you choose” at the 1931 Institute (EHS to ES, 11 December 1930, Edgar Howard Sturtevant Letters/LSA Archives). 1937 was the only year Sapir taught at an Institute. However, in 1982 the Society launched the Fund for the Future of Linguistics with a challenge grant of $75,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The goal was $300,000, to be reached by 1984, which happened to be the centennial year of Sapir’s birth. That proved a convenient fund-raising device; one category on the pledge sheets listed “the Edward Sapir Professorship” (Bul 101, p. 10, 1983), and Sapir became the “poster child” for the campaign. The Ken Hale Professorship, established in 2003, was also funded through a matching grant from the NEH. Edward Sapir on cover of LSA Bulletin Difficulty in attracting a host every year and the increasing costs of the Institutes seem to have been the main factors leading the Executive Committee to reduce the frequency with which they were held. In 1988 an announcement appeared in the March Bulletin. Encased in a black box and printed in bold black letters, it was headed “No 1988 Linguistic Institute” and reported that “Beginning in 1987, Linguistic Institutes will be every two years, in odd-numbered years” (Bul 119, p. 8, 1988). There was no mention of the summer meetings which had been held ever since 1938, but they were eliminated from the Institutes’ schedules at the same time. LSA Bulletin No. 119 (1988) It should be noted that the summer meetings of 2006 and 2008, held at Michigan State University and The Ohio State University, respectively, were de novo creations. These two meetings were focused on the needs and interests of students. That was never true of the summer meetings held from 1938 to 1988. Those were an integral part of the “gathering of scholars” which has always been the heart of the Linguistic Institutes. Modern Institutes are held less frequently than in their first half-century, and their length has been shortened to four weeks. They also cost more: $500,000 to $700,000 in recent years (www.linguisticsociety.org/files/request-for-proposal.pdf). But, compared to Institutes of the 1950s and 60s, they have more than doubled the numbers of faculty, courses, and enrollments. At the most recent Institute, held at the University of Michigan in 2013, there were over 80 faculty and nearly 70 courses (http://lsa2013.lsa.umich.edu/), with 505 enrollments (source: LSA Secretariat, December 12, 2014). A Forum Lecture was presented by Noam Chomsky to 1,000 people in Rackham Auditorium. Noam Chomsky 2013 Forum Lecture Placed on YouTube by the LSA Secretariat, that lecture is now available to everyone, everywhere. Edgar Sturtevant would be amazed -- and very pleased. References and Other Sources Bul = Linguistic Society of America Bulletin No. 1- 1926- Cowan, J Milton. 1991. American Linguistics in Peace and at War. First Person Singular II: Autobiographies by North American Scholars in the Language Sciences, ed. by Konrad Koerner, 67-82. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Falk, Julia S., and John E. Joseph. 1994. The Saleski Family and the Founding of the LSA Linguistics Institutes. Historiographia Linguistica 21:1/2.137-156. Falk, Julia S., and John E. Joseph. 1996. Further Notes on Reinhold E. Saleski. Historiographia Linguistica 22:1/2.211-223. Falk, Julia S. 1997. Defining Linguistics: E. H. Sturtevant and the Early Years of the Linguistic Society of America. Proceedings of the 16th International Congress of Linguists. Oxford: Pergamon, Paper No. 0029. Falk, Julia S. 1998. The American Shift from Historical to Non-Historical Linguistics: E. H. Sturtevant and the First Linguistic Institutes. Language & Communication 18.171-180. Falk, Julia S. 2001. Hahn, E. Adelaide. American National Biography Online. www.anb.org/articles/14/14-01105.html Falk, Julia S. 2002. Pike, Kenneth Lee. American National Biography Online. www.anb.org/articles/14/14-01122.html Falk, Julia S. 2003. Sturtevant, Edgar H. American National Biography Online. www.anb.org/articles/14-14-01129.html Hill, Archibald A. 1963. History of the Linguistic Institute. ERIC Document ED 018172 from “the 1964 Bulletin of the Indiana University Linguistic Institute.” Also published in ACLS Newsletter 15:3. Joos, Martin. [1986]. Notes on the Development of the Linguistic Society of America 1924-1950, with a Foreword by J M. Cowan and C. F. Hockett. Private publication distributed by Spoken Language Services, Inc. Report of the Special Committee on the Linguistic Institute. 1940. Linguistic Society of America Bulletin 13.83-101. (Supplement to Language 16:1). Contains Sturtevant 1940 and Report on Responses to Linguistic Institute Questionnaire. Sturtevant, E. H. 1940. History of the Linguistic Institute. Linguistic Society of America Bulletin 13:8389. (Supplement to Language 16:1). Sturtevant, E. H. 1947. Linguistics and the American Council of Learned Societies. Language 23.313316.