The Effects of Culture on Negotiations Between Danish and

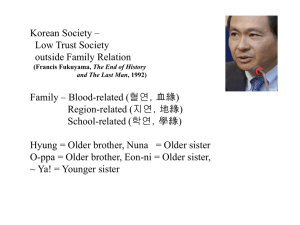

advertisement