File

advertisement

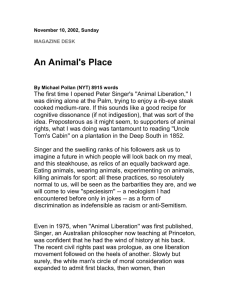

Josh Sivley Dr. Jane Drexler Philosophy 2300 08/02/2011 To Eat or Not to Eat: That is the Question If we let dogs be dogs, and breed without interference, we would create a sustainable, local meat supply with low energy inputs that would put even the most efficient grass-based farming to shame. For the ecologically minded it’s time to admit that dog is realistic food for realistic environmentalists. (Jonathan Safran Foer, Eating Animals p. 28.) While Foer’s recommendation may seem offensive or extreme, it invokes the question: who is due moral/ethical consideration, and where should the line of tolerance be drawn? It is my intention to explore three philosophical theories, as well as the underlying moral framework relating to the moral dilemma of eating animals. I’ll also reflect on the individual challenges that arise when one seriously considers the implications of these arguments for the first time. The philosophical framework underlying Peter Singer’s theory of what matters morally can be broadly labeled “utilitarian,” a framework that what is ethical is what promotes the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people possible. Singer uses this tenet to argue that an action is justified if it promotes the maximum pleasure; it is unjustifiable if it produces suffering. Singer takes it this utilitarian view point a step further as he applies this same principal to animals; he argues that animals are owed moral recognition on the basis of sentience, that is, their ability to experience pleasure and pain. Singer plainly states that “if a being suffers, there can be no moral justification for refusing 1 to take that suffering into consideration” (All Animals Are Equal p. 108). Here Singer draws a distinct line of tolerance between beings who are capable of suffering and those who are not. He goes on to say that the “nature of the being” should not even be a consideration when considering the moral worth of a being, arguing that it would be illogical to draw a moral line between any sentient beings. According to Singer, “To mark this boundary by some characteristic like intelligence or rationality would be to mark it in an arbitrary way. Why not choose some other characteristic, like skin color?” (All Animals Are Equal p. 108). Clearly, if we were to choose the arbitrary characteristic of skin color as criteria for moral recognition (as we did with Black Americans), we would immediately be recognized as a racist, as one who believes in one’s superiority relative to those differing in race. Singer applies this same principle of supremacy to those of differing species when he says “the speciesist allows the interests of his own species to override the greater interests of members of other species” (All Animals Are Equal p. 108). Here Singer does an outstanding job illustrating just how illogical (yet common) it is to draw the line of separation based on species rather than the similarity found in our shared desire to avoid suffering. When one truly looks into the eyes of a suffering sentient being, it is very difficult to deny that we are equal; one can sense the anguish and misery felt by this being and even more so -- relate to it. Tom Regan believes that the utilitarian's criteria for moral recognition is insufficient because it fails to show that differential treatment of animals violates their equality (Animal Rights, Human Wrongs p. 110). Regan argues that Singer’s 2 assumption (that we should not do to animals what we would not do to humans) is not a sufficient standard by which to argue against the mistreatment of animals. In short, the fact that humans’ and animals’ nutritional needs are different does not justify different ethical standards with regard to suffering. Regan’s criteria for morality is based on what he calls “being a subject of a life.” I understand this statement to mean more than that one is merely alive; to be “a subject of a life” one must have the ability to sense discomfort, or have a sense that his or her basic instincts are being hindered. Regan points out that humans have inherent value when he asserts that “Human beings have inherent value because, logically independently of the interests of others, each individual is the subject of a life that is better or worse for that individual” (Animal Rights, Human Wrongs p. 116). After Regan establishes the fact that humans have this value, he goes on to say that if we use another human for personal gain we are violating their right to not be harmed. Regan goes one to say that the same logic is applicable to animals who are “a subject of a life.” Regan recognizes the similarity between animals and humans when he states “They too have a distinctive kind of value in their own right, if we do; therefore, they too have a right not to be treated in ways that fail to respect this value, if we do. And, like humans, this right of theirs will be overridden unjustifiably if they are harmed merely to advance the profits or pleasures of others” (Animal Rights, Human Wrongs p. 116). Regan makes it hard for those holding an anthropocentric view of life to differentiate between the inherent value of humanity and all who are “a subject of a 3 life.” While Reagan and Signer disagree on the underlying moral framework of their theory's they both would agree that violating a beings inherent value is morally impermissible; thus both would be opposed to the consumption of animals Michael Pollan takes a different approach to the moral dilemma at hand by examining the relationship we have with our food. Pollan feels that our eating habits are a representation of our interaction with the natural world, calling this interaction industrial eating. He illustrates this concept when he states “ No other country raises and slaughters its food animals quite as intensively or as brutally as we do”(New York Times Magazine, “An Animal’s Place” p. 25). The ferocious fashion in which we cultivate our animals is a perfect example of the detrimental effect “industrial eating” can have -- further fueling the deterioration of how humanity views nature. This numb perception of animals as nothing more than a form of income and is best described by Pollan when he states “life itself is redefined -- as protein production -- and with it suffering” (p. ). Pollan argues that animals are due respect and that “industrial eating” is robbing them of that respect. Pollan finds himself grappling with the dilemma to either disregard the brutal fashion in which we obtain our meat, or to stop eating it all together. This internal battle leads Pollan to a third alternative which he calls “humanocarnivore.” He describes this approach as the limitation of meat consumption solely to nonindustrial animals; this, he says, is “the only sort of meat eating I feel comfortable with.” (New York Times Magazine, “An Animal’s Place” p. 25) Pollan can find solace in this decision as he reflects on farms and ranches 4 where animals are able to exist in a peaceful and healthy environment, free from brutal mistreatment. For Pollan the practice of eating meat is permissible if the animals are treated with the conscious respect they are due. I admire Pollan for his optimism that humanity can still engage in a respectful relationship when eating animals and I’m sure many will adopt this theory. However, it is my fear that they will do so as a moral compromise between consciously acknowledging the injustice being done and turning a blind eye or stopping the consumption of meat. When one is raised in an agriculturally industrialized world it is easy to be unaware or ignorant of the process involved in getting meat on the dinner table. However, once one recognizes the brutal fashion by which facilities “process” animals, he/she confronts a difficult decision. Author Jonathan Safran Foer illustrates this dilemma well when he says Whether I sit at the global table, with my family or with my conscience, the factory farm, for me, doesn't merely appear unreasonable. To accept the factory farm feels inhuman. To accept the factory farm -- to feed the food it produces to my family, to support it with my money-- would make me less myself, less my grandmother's grandson.... This is what my grandmother meant when she said, 'If nothing matters, there's nothing to save.' (Eating Animals p. 267) I admit it—I love eating “meat.” Despite the inconvenient truth suggested by all three of the above philosophers with regard to animals, history has shown us that ignorance of the “other” has been used to justify inequality and failure to consider the moral basis for our behavior. In closing, I think the following quote by Henry Beston serves to remind us of our often misguided assumptions about, and 5 by implication, our potentially profound misunderstanding of animals and their rights as sentient creatures. We need another and wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. . . . In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth. (The Outermost House, Henry Beston) 6 Works Cited Henry Beston "The Outermost House" (1928; 1956) Reprinted by Holt, Reinart, & Winston. Nevada City: California. Jonathan Safran Foer, "Eating Animals," 1st ed, November 2009, 28-267 Michael Pollan, "An Animal's Place," New York Times Magazine, November 10, 2002 Tom Regan, "animal Rights, Human Wrongs," from Environmental ethics, Vol 2, No 2. (summer 1980), 110-116 Peter Singer, "All Animals Are Equal," from Philosophic Exchange, Vol. 1, No. 5 (summer 1974), 108 7