Final Draft 2 - Tani's ePortfolio

advertisement

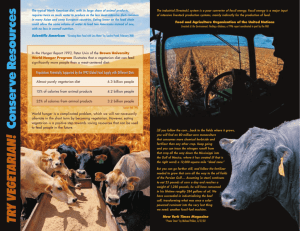

Hatch 1 Tani Hatch Professor Drexler PHIL 2300-F13 6 December 2013 A Necessary and Surmountable Compromise A living being is brought into this world but it is confined to a small dark space where it is not provided enough room to turn around or even sit down. The purpose of this young bobbie calf to live its short, tragic, and stunted life is nothing but to provide its pale and purposely-made anemic flesh to humans (Regan, 102). “Multiply these cases by the hundreds, multiply them by the thousands, and we approach, perhaps, the magnitude of the death and suffering animals are enduring, at this moment, at the hands of human beings…As for slaughter, incomplete data suggest that, worldwide, the number of animals killed for food exceeds hundreds of millions for individual species, involving upwards of one hundred million cattle…two hundred million pigs…and, in the United States alone, three billion chickens…Few things now call forth less collective compassion of humankind than the great suffering animals endure in the name of human interests” (Regan, 102-104). For these reasons the question becomes: Are we obligated to become vegetarian, morally? We are morally obligated to adopt a vegetarian diet because of the current horrendous conditions, practices, and treatment of the industrial livestock; however, eating meat is not inherently wrong and is still morally permissible with a “humanocarnivore” diet which would limit the meat that you do consume in moderation to strictly nonindustrial animals whose inherent value is recognized and they are treated throughout their lives with the respect they deserve (Pollan, part 2, pg 7). There are many philosophers who have provided Hatch 2 concepts and theories that provide some explanation as to how this shift in attitude and behavior towards these animals came to be and what we should do about it. Carolyn Merchant, Ph.D, a former president of the American Society of Environmental History and current professor at Berkeley University, discusses in her book The Death of Nature how there was a shift in the mentality towards nature from it being organic and, “a kindly beneficent female who provided for the needs of mankind,” to a, “mechanically oriented mentality that either eliminated or used female principles in an exploitative manner” (270). This shift in mentality led to a shift in the treatment of our land and everything within it. “The image of the earth as a living organism and nurturing mother had served as a cultural constraint restricting the actions of human beings” (270). Now that the image and resulting cultural constraint had been removed, we could treat the land and everything that constitutes it, including livestock, without any regard for its intrinsic value. Richard Sylvan, an ecologist, philosopher, and university professor, recognized that we needed a new environmental ethic because of this shift in mentality and treatment toward nature. In his article, “Is There a Need for a New, Environmental, Ethic?” he explains that, “The main point to grasp…is that ethical principles if correct are universal and are assessed over the class of ideal situations” (16). What Sylvan means is that regardless of the situation, if the ethics are correctly constructed, they will support an outcome that is morally permissible. This may also mean that we have to sit down and re-examine some of the most basic components of ethics such as, “natural right, ground of right,” and even, “traditional analyses of such notions as value and right” (18-19). We do need an environmental ethic that can and must be applicable in a universal way because this will provide for ethical and dignified conditions of farm animals thus giving them a higher quality of life. In turn, this would allow us to adopt a humanocarnivore diet Hatch 3 with greater ease or stick to a vegetarian diet for reasons other than poor livestock treatment and living conditions. Paul Taylor, Ph.D continues with this train of thought that perhaps there are some aspects to which morality, ethics, and ranking are defined that need to be re-evaluated. In his article, “The Ethics of Respect for Nature” he questions our superiority to “other animals” and why. He diagnoses a cycle of false logic that’s called begging the question which means that you are stating the conclusion that is also included in your premises. “Humans are claiming superiority from a strictly human point of view…in which the good of humans is taken as the standard of judgment. All we need to do is to look at the capacities of nonhuman animals (or plants, for that matter) from the standpoint of their good to find a contrary judgment of superiority” (79-80). An example of this would be the comparative sprinting speed of a human and cheetah for which the cheetah would clearly take the cake; they are superior to us in that way. Humans have allowed themselves to sit up on a pedestal and treat everything else around them (e.g. the environment, air, land, animals) however they please. This cannot and should not be the case. These domestic animals are not being treated fairly as to their worth and their dignity is being ignored because we are placing value in them (or not) from what is important ranking criteria only to humans. Once we reconnect with the notion that these livestock who provide our sustenance have inherent value, we will change the horrific conditions that they are forced to endure. Until the point of change, we morally obligated to adopt a vegetarian or humanocarnivore diet. Another debate arises which asks what makes nonhuman animals worth of our moral consideration. “If possessing a higher degree of intelligence does not entitle one human to use another for his own ends, how can it entitle humans to exploit non-humans?” (Singer, 106-107). Peter Singer, a philosopher, author, and former president of the Animal Rights International, Hatch 4 brings to light the concepts of sentience, equality, and speciesism with respect to animals. His, “aim is to advocate…that we extend to other species the basic principle of equality that most of us recognize should be extended to all members of our own species” (103). This would entail the expansion of the members in our moral circle, the very circle which determines who we consider morally when making decisions, from humans to nonhuman animals. Singer admits that there are differences between humans and nonhuman animals, yet, “The extension of the basic principle of equality from one group to another does not imply that we must treat both groups in exactly the same way, or grant exactly the same rights to both groups…The basic principle of equality, I shall argue, is the equality of consideration” (104). He elaborates on that statement by explaining that the equality shared amongst all human beings is not based upon the descriptions and characteristics of each individual, but it, “is a moral idea…it is a prescription” (105-106). But this prescription of equality is not just limited to the grouping of humans as he presses for the inclusion of nonhuman animals in the moral circle. Singer lends support for another philosopher’s view, Jeremy Bentham, which, “points to the capacity for suffering as the vital characteristic that gives a being the right to equal consideration” (107). The extension of the moral circle includes sentient beings that are able to experience pain, suffering, and joy. “To avoid speciesism we must stop this practice, and each of us has a moral obligation to cease supporting the practice” (Singer, 109). The way in which we can do this would be to adopt a vegetarian or humanocarnivore diet instead of supporting meat production under its current practices. A philosophical view that interjects the concept of rights in dealing with animals and how they are treated is added into the mix by Tom Regan, an American philosopher who previously held a position as a professor of philosophy at the North Carolina State University for many Hatch 5 decades. He explains, as humans we claim to have intrinsic value, therefore, that gives us basic moral rights. “Consistency requires that we attribute this same kind of value to many animals,” which, “provides a similar basis for attributing certain basic moral rights to them, including the right not to be harmed” (99). Regan continues that humans, “are the subjects of a life that is better or worse for us, logically independent of anyone else’s valuing us or finding us useful,” and that there are animals who fall under that same criteria (116). By giving animals intrinsic value, this would help establish a standard for industrial farming which would help to alleviate this moral instated vegetarianism. “This does not mean that there are no circumstances in which an individual’s rights must give way to the collective interest,” but that, “individual rights then normally, but not always, trump collective interests” (113). Amazingly, some installations of animal rights have already taken place in some parts of the world. “Germany became the first nation to grant animals a constitutional right: the words “and animals” were added to a provision obliging the state to respect and protect the dignity of human beings…The Swiss are amending their laws to change the status of animals from “things” to “beings”” (Pollan, part 1, pg 1). While this rights approach doesn’t completely rule livestock out of our diet, it at least takes a step in the right direction, especially if people cannot make the moral decision within themselves. I think the conversion of paying more attention to those individual rights, the treatment during their lives and deaths, will have more weight than the mouths they will end up feeding if done correctly and compassionately. I’m not sure who in their right mind would trot off to a steakhouse for a rib eye steak while committing themselves to read through and critique Peter Singer’s book Animal Liberation, but this author of multiple books and professor at UC Berkeley bites the bullet and carries through with it. In his two part article published in the NY Times entitled, “An Animal’s Hatch 6 Place” Michael Pollan admits that he finds it hard to contest any of Singer’s arguments. This leads him to the thought that we either become vegetarians or we eat meat and look away from the conditions under which it is produced. However, “Steve Davis, an animal scientist at Oregon State University, has estimated that if America were to adopt a strictly vegetarian diet, the total number of animals killed every year would actually increase, as animal pasture gave way to row crops…It would appear that killing animals is unavoidable no matter what we choose to eat” (part 2, pg 5). Which leads us to, “the fact that we humans have been eating animals as long as we have lived on this earth. Humans may not need to eat meat in order to survive, yet doing so is part of our evolutionary heritage, reflected in the design of our teeth and the structure of our digestion. Eating meat helped make us what we are, in a social and biological sense” (part 2, pg 5). It’s hard to say at this point that strict vegetarianism is the only morally viable solution to this problem we face with industrial livestock because if meat has in some way always been in our diet, it probably always will. With this in mind, Pollan visits a farm run by Joel Salatin; a man who values and respects his livestock’s animality and ensures that his animals live and operate under those naturally prescribed conditions and behaviors. “In the same way that we can probably recognize animal suffering when we see it, animal happiness is unmistakable, too, and here I was seeing it in abundance” (part 2, pg 3). For domesticated livestock, he explains that they have a symbiotic relationship with humans which can give them a higher quality of life and death then they would receive in the natural world. Pollan does find it morally permissible to eat the meat from animals such as those on this farm that are treated and valued this way. With this in mind, Michael Pollan concedes that, “If there's any new ''right'' we need to establish, maybe it's this one: the right to look” (part 2, pg 7). Hatch 7 There must be a change in the treatment and management of these animals in order us to maintain that eye contact without any associated shame or guilt. And yet, “In order to have meat on the table at a price that people can afford, our society tolerates methods of meat production that confine sentient animals in cramped, unsuitable conditions for the entire durations of their lives. Animals are treated like machines that convert fodder into flesh” (Regan, 108). But Tom Regan puts it brilliantly that, “Difficult questions are like knots; they are not unraveled just by pulling hard on one idea” (104). While adopting a vegetarian diet is one viable option to the issue at hand, it won’t suffice as a solitary solution. Engaging in a humanocarnivore diet where meat consumption is done in moderation and only from nonindustrial animals who lived and died respectably is another feasible route. It is also helpful to know the history of this shift of perspective and treatment towards nature along with the progression that has been made in trying to reconnect to our previous stance towards nature. “Were the walls of our meat industry to become transparent, literally or even figuratively, we would not long continue to do it this way…Yes, meat would get more expensive. We’d probably eat less of it, too, but maybe when we did eat animals, we’d eat them with the consciousness, ceremony and respect they deserve” (Pollan, part 2, pg 7). This change in treatment towards animals is an entirely possible feat for the people of our time. Hatch 8 Works Cited Merchant, Carolyn. “The Death of Nature,” Environmental Philosophy: From Animal Rights to Radical Ecology (1st edition). Michael Zimmerman (ed.) (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993), ISBN: 0-13-666959-x Pollan, Michael. “An Animal’s Place,” New York Times Magazine. November 10, 2002. Regan, Tom. “Animal Rights, Human Wrongs,” from Environmental Ethics, Vol 2, No 2. (Summer 1980). Singer, Peter. “All Animals Are Equal,” from Philosophic Exchange, Vol. 1, No. 5 (Summer 1974). Sylvan (Routley), Richard. “Is There a Need for a New, Environmental, Ethic?” Environmental Ethics: An Anthology. (Andrew Light and Holmes Rolston III, eds.). (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), ISBN-13: 978-0-631-22294-1. Taylor, Paul. “The Ethics of Respect for Nature,” Environmental Ethics: An Anthology. (Andrew Light and Holmes Rolston III, eds.). (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), ISBN-13: 978-0-631-22294-1.