English Press Release

advertisement

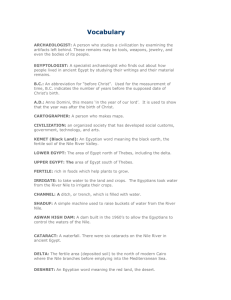

Growing Thirst – Sustainable Water Solutions for Egypt – The 13th Cairo Climate Talks (CCT) event discussed how climate change impacts Egypt’s water supply and demand and how the implications can be addressed with sustainable solutions Panelists agreed the problems and solutions are known, but a greater sense of urgency in addressing the issues has to be developed. This could be achieved by more stringent enforcement of existing laws and the implementation of new initiatives. The evening began with a summary by Professor Dr. Torsten Schmidt from the Instrumental Analytical Chemistry and Centre for Water and Environmental Research (ZWU), University of Duisburg-Essen, on the outcomes of the Sustainable Water Technologies Workshop held in Cairo from February 18 th to 20th. “It was agreed that a holistic approach is needed because the various issues related to water cannot be treated separately, we need to talk about the whole water cycle and its connections to food and energy. We have to talk about quantity, which is a critical issue in Egypt, but we cannot forget about quality,” Dr. Prof Schmidt said. “Water knows no boundaries and the Nile crosses borders, it is a trans-boundary issue and we need transboundary solutions, responsibility shouldn’t be fragmented,” he continued. According to Prof. Dr. Schmidt, it is necessary to include people because they are affected by water issues in their everyday life. “Increased efforts need to be made to make people aware water is an issue,” he noted. Dr. Tarek Kotb, First Assistant Minister in the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, said the key challenges Egypt faces in developing sustainable water solutions are limited water resources, population increase, increased pollution, and the energy required to pump water from the canal to the lowlands. In 1959, an agreement was made between Egypt and Sudan regarding each countries fixed annual share from the Nile. Egypt was allocated 55.5 billion cubic meters. At the time, Egypt’s population was 20 million. There are now 85 to 90 million people using the same amount of water, and population forecasts for 2050 put Egypt at 160 million. “There are already very limited resources and opportunities to increase water sources are very limited, we will be living under very stressing water conditions,” Dr. Kotb noted, “this constrains development plans, as water is the fundamental source for all development activities.” “Pollution is increasing. Industries and factories along the Nile discharge waste into the river. If the water is polluted, to a certain extent, it is lost unless we manage to treat it, or reuse it by mixing with fresh water, but there is no guarantee of the quality after,” he continued. Prof. Dr. Ali Müfit Bahadir from the Institute of Environmental and Sustainable Chemistry, Technische Universität Braunschweig, noted the ability of the Nile to recover quickly on its own if discharge and pollution are not put into it. “We can do this by building treatment plants. If we stop the pollution at the sources we’ll have better quality water to begin with,” he said. Dr. Kotb noted there are very strict laws in place for pollution and maintaining Nile water to certain standards, but the problem lies in the enforcement of the law. With the onset of climate change, Dr. Kotb acknowledged more water will be needed to combat temperature increases, rising sea levels will threaten the fertile land of the Nile delta and the overall flow of the Nile will be affected. Claudia Bürkin, Water Sector Coordinator for the German Development Cooperation and Senior Programme Manager at KfW Development Bank, said Germany is working on projects with Egypt centered around the challenges noted by Dr. Kotb, focusing on domestic use, for water supply and sanitation, and water for agriculture. “We’re financing large scale projects in Upper Egypt to build capacity and increase coverage, as in some areas it’s as low as 12%,” she noted. “We’re also working with the ministry in institutional reform to have better processes and coordination,” Bürkin said. Lama El Hatow, Co-founder of the Water Institute of the Nile (WIN), said a group of people unhappy with the way the government was dealing with the Nile basin issue came together to discuss how to overcome certain obstacles and find win-win solutions across Nile basin states. “Track one diplomacy was coming to a halt. We felt the need to become engaged in track three, or civic, diplomacy. Since the revolution, civil society engagement and dialogue with the government has significantly improved but we still have a long way to go,” Hatow explained. Hatow said WIN gives a voice to the voiceless, “Acting as a lobby group, we can work with the governments to inform them what stakeholders on the ground want and the different types of agitation they are experiencing.” Reflecting on the steps that need to be taken, Dr. Kotb remarked, “There are a lot of efforts being made. We know the problems and we know all the solutions, but sometimes you cannot implement the solutions because it’s not always your decision.” “The government has set a criterion that no new factories can be built close to water sources; they must be a minimum distance of 30km. The government has also decided that no more Nile water can be utilized to build new settlements outside of the Nile Delta area,” he added. “Water is a societal problem and needs to be solved in a participatory way, we want to hear the voice of civil society and hear a commitment from their side as well. We need to reach every Egyptian with the message: water is very precious, it is getting very limited and it will be even scarcer in the future,” said Dr. Kotb. Bürkin emphasized the importance of coordination between different ministries, “Egypt is on track, but needs more integrated management. There might be other political priorities to overcome in the current situation, but there is a need for joint planning, coordination and setting priorities. Egypt has also started a reform process, but more decentralization is needed.” “We’re doing a lot of talking in Egypt, but need to focus on getting things done,” Bürkin said, stressing the urgent nature of the problems. Hatow noted there is a need for a paradigm shift. “Instead of looking at the situation as a penalty system, how can we give people incentives to change? How can we provide incentives to farmers to change their water habits? These kinds of solutions are what we’re proposing to the government to promote best sustainable practices on the ground,” she said. Prof. Dr. Bahadir highlighted the opportunities for Egypt and Germany to work together. “We’re ready to bring knowledge and information to Egyptian partners and work on emerging problems. We can learn from each other how to transfer our experiences to local conditions. You cannot do anything from outside. You have to do it with local science and local administration,” he concluded.