Potential to Revive Extinct Animals Raises Ethical

advertisement

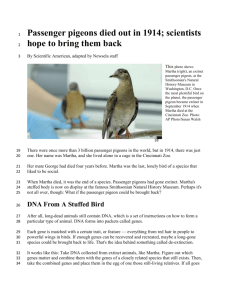

Potential to Revive Extinct Animals Raises Ethical Questions – Informational Text Though it may sound like "Jurassic Park," researchers and entrepreneurs are now trying to bring back extinct species. Some scientists believe it’s a way to correct past mistakes and even help endangered animals. Dinosaur DNA is too old to offer viable genetic material, but scientists are focusing on species that went extinct more recently and whose DNA still exists. Researchers have already revived one extinct animal. A species of mountain goat was cloned in Spain in 2003, but the clone only lived a few minutes. Other scientists are working on bringing back the wooly mammoth, who they believe may help stop ice loss in the Arctic, and the passenger pigeon, which was once the most abundant bird species on the planet. "In the early 1800s, there were five billion of these birds just in the United States. Within the span of about 50 years, they go extinct," said Ben Novac of Revive and Restore, who is working on a way to revive the species. The birds went extinct in 1914 due to over hunting. "It opens the door to this brand-new future of conservation, in which we can finally shift gears from thinking that we’re losing life on this planet to the fact that we are actually gaining it back." To de-extinct the passenger pigeon, Novak plans to genetically engineer its closest relative, the bandtailed pigeon. He would insert genes he obtained from passenger pigeon museum specimens. This is a painstaking process, as DNA is degraded and it’s hard to identify what genes do what. Novak would like to replace band-tailed pigeons’ square tails with the long tail and swift wings that allowed passenger pigeons to fly at 60 miles per hour. However, some scientists are concerned about the ethical implications of bringing back extinct species. "We’re lost, unless we realize that we’re just a part of this intricate web. And we ought to bring species back if they can help maintain that web, but not because it makes us feel better and sleep better at night," said Jim Patton, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley.