2nd Block Click Here CISM Coded Vocabulary

advertisement

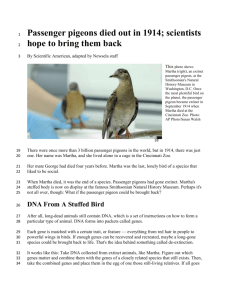

Name_______________________ Block_________ Passenger pigeons are extinct, but scientists hope to bring them back This photo shows Martha (right), an extinct passenger pigeon, at the Smithsonian's Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C. Once the most plentiful bird on the planet, the passenger pigeon became extinct in September 1914 when Martha died at the Cincinnati Zoo. Photo: AP Photo/Susan Walsh Martha, the last passenger pigeon, died alone in a cage in the Cincinnati Zoo. It was 1914. Her mate had died four years before. There were once 3 billion passenger pigeons. Martha was the last of a social species. Her stuffed corpse can now be seen at the Smithsonian Institution. But what if the passenger pigeon could be brought back? After all, long-dead animals still contain DNA — genetic material that is a set of instructions on how to form a particular species. Packets of DNA combine to form genes associated with a particular trait. If enough of those genes can be recreated, perhaps a long-gone species could be brought back to life. That's the idea behind something called de-extinction. De-Extinction Pioneer It works like this: Take DNA harvested from specimens stuffed in museum drawers, like Martha. Figure out which genes matter. Then, use genetic engineering to edit the DNA of a closely-related species into some version of the extinct species. If all goes well, a copy of the long-lost Martha could be born and, one day, flocks of passenger pigeons could fly in the skies. De-extinction pioneer Ben Novak is working to make this come true. Novak's is focused on collecting genetic information from stuffed passenger pigeons and studying the genetic makeup of the band-tailed pigeon. The passenger pigeon and the band-tailed pigeon are closely related. So far, 32 passenger pigeon samples have had their genomes sequenced. "Genome" is simply the word for the complete set of genes found in an individual animal. "Sequencing" refers to the process of figuring out the order of the genome's parts — that is, the order of its DNA bases. Just as the words in a sentence need to be in a certain order to make sense, DNA bases need to be ordered in a particular way for genetic information to be communicated. A unique sequence is what creates an animal's particular genetic profile. All of Novak's passenger pigeon samples come from birds killed between 1860 and 1898, "right in the range when the bird was going extinct," he notes. Population Booms And Busts Novak has also been helped by outside efforts, including the nearly complete sequencing of three passenger pigeons. The genes of those three birds show that passenger pigeons have been through population booms and busts before — their numbers have risen and fallen at different times. Passenger pigeons have gone through times in their evolutionary history when their populations were quite low, notes geneticist Beth Shapiro. This means that scientists may be able to restart the species with a small group of birds that can be sustainable and grow on its own. "All of our birds," Novak adds, are "very, very similar to each other — like everybody being cousins." Novak believes that similarity was caused by a recent burst of rapid population growth. He and his team are interested in figuring out when that population growth happened. To figure out when the last boom happened will require finding DNA from fossil samples thousands of years old. Novak has already begun to examine a few of these samples. With ancient samples and those from the 19th century, Novak and others can begin to figure out how the bird lived in the wild. Understanding that will help them decide if a restored passenger pigeon could thrive and succeed in the woods available today. Nothing Novak has learned so far, he says, tells him to "turn back now and not bring back the passenger pigeon." Who'll Teach The Baby BIrds? Novak's team has not yet completed the band-tailed pigeon sequencing required to begin resurrecting the passenger pigeon. However, experiments with cells from the band-tailed pigeon may begin as soon as next year. If the de-extinction works, the only remaining challenge would be to teach the new birds how to be passenger pigeons. Doing that would likely be even more challenging than the genetic work itself. The new birds would be part band-tailed pigeon, and would have no passenger pigeon parents to teach them what to do. To understand the difficulty, one need only look at similar efforts — such as attempts to teach cranes to migrate by using ultralight airplanes. Still, if everything goes well, birds that carry the genes of the passenger pigeon could be flapping around by the end of the decade. The project may be too ambitious, however. Similar efforts that stretch back 30 years have so far failed to produce a quagga, an extinct species of zebra. In 2003, scientists resurrected a bucardo for seven minutes, but that experiment has yet to be repeated. Nevertheless, conservationists are examining how the science used for de-extinction might be used to preserve endangered animals and plants or bring them back if they die out. There are advantages, however, to working with an animal that is already extinct. These scientists have no need to hurry. After all, Martha died 100 years ago. If they succeed, the world gets a new kind of bird, Novak says. "If we fail, we learn things that are valuable and the world isn't left with another extinct species."