Linguistic grammar glossary

advertisement

Accent and dialect

Accent refers solely to the way words are pronounced, e.g. in the south of

England, it is normal to pronounce the word path as p-ar-th, but in the

Midlands and the North, the phoneme 'a' is articulated as a short vowel and

pronounced as in, 'cat'. The accent known as 'Received Pronunciation' is

considered as a prestige accent and is one frequently heard on television and

radio news bulletins, for example.

Dialect refers to choices of vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation made by

people in different geographical regions or social contexts. The dialect known as

'Standard English' is generally considered to be a prestige dialect and is the

choice of many teachers, business people, newsreaders, etc.

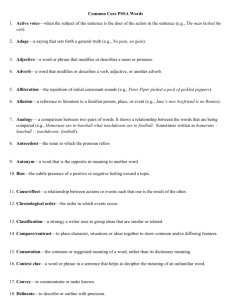

Active and passive

This is an important stylistic choice that concerns the way we use verbs. A

voice

typical English sentence will be cast in what is called the active voice, e.g.

'The teacher led the lesson'. In such a sentence, the subject (S) is also the

agent of the action told by the verb (V). This action is transferred to the

object of the sentence (O).

A different type of sentence construction is possible. In this, the subject

position can be filled not by the agent but by what, in the active sentence, was

the verb's object, e.g. 'The lesson was led by the teacher.' The grammatical

subject position is now filled by the noun phrase, 'the lesson' and the agent

becomes a part of a phrase that follows the verb, introduced with the

preposition 'by': 'by the teacher'. This is called a passive construction.

Importantly, passive constructions can even allow for the agent to be deleted

and the sense still retained, e.g. 'The lesson was led'. This makes passive

sentences potentially interesting as they can be made to carry a different

pragmatic force, one that leads to different inferred meanings being

created.

By fronting the object in place of the subject, the force of the sentence can be

changed and the role of the agent can be diminished. Passive constructions are

popular in newspaper headlines as it gives a concise, authoritative and

impressive style but one that does not risk 'pointing the finger' of blame, e.g.

'Woman murdered in gangland shooting'. Here the subject is not even

mentioned. See also voice.

Adjective

A word class which contains words that can add more detail (i.e. modify) to a

(adjectival)

noun or pronoun with which they often form a noun phrase, e.g. 'The busy

teacher' (pre-modification).

Adjectives can also post-modify a noun, as in: 'The dinner was awful'.

Adjectives are gradable depending on whether a comparison is made with one

other thing or many other things: big, bigger, biggest difficult, more difficult,

most difficult.

Agent

The grammatical agent is the participant in a clause or sentence that carries

out the action told by a verb. In the following sentence, the 'cat' is the

agent: 'The cat sat on the mat'. In the passive form of this sentence, 'The mat

was sat on by the cat', the 'cat' remains the agent, but the subject now

becomes 'mat'.

It is easy to confuse the two terms agent and subject: the word subject

refers syntactically to the word in a sentence or clause that is grammatically

linked to a verb and which makes the verb finite. For more, see

active/passive.

Agreement

In English grammar, it is necessary that certain linked words 'agree' with each

other, for example, a verb is given an inflexion (suffix) to allow it to 'agree

with' its subject when in the 'third person', e.g. he talks (not he talk).

Adverb

A class of words (many ending with the suffix -ly) that are often found helping

(adverbial)

to modify a verb in order to provide extra detail about the way the action told

by the verb occurred; however, adverbs are also used to modify other adverbs

or adjectives, e.g. 'The girl worked especially hard.' 'He was just too much!'

Adverbs can give detail concerning time (soon), place (there) and manner

(nearly). Adverbs tend to give extra detail about time, place or manner.

'Adverbial'

A phrase that acts like an adverb to provide extra information about time,

place or manner. A sentencecan contain several adverbials (which, unusually,

can be located in more than a single syntactical position without any change of

function). Adverbials are usually 'optional' elements in a clause - its central

meaning being unaffected if they are left out.

Ambiguity

Twice

during each day

ADVERBIAL

ADVERBIAL

manner

time

I exercise

SUBJECT+VERB

in the gym

in town

ADVERBIAL ADVERBIAL

place

place

This means 'more than one possible meaning'. The rules of grammar exist to

allow a structure of words to be created that has a single meaning, i.e. to be

unambiguous. Here is an ungrammatical sentence that was an actual warning

notice at the bottom of an escalator: 'Dogs must be carried on the escalator'.

What does this mean? Are you allowed to ride on the escalator without a dog in

your arms?

Archaic

If a word is described as archaic, it suggests its use is now old-fashioned.

(archaism)

Many words in poems are still used that seem archaic, and many formal words

may seem to be so, especially in a religious or legal register. Such words may

not be really archaic - it may simply be that you are unaware of these

particular registers. Take great care when writing about language in A2

change not to label a word archaic simply because you haven't heard of

it - better to say 'formal'.

Article

One of a class of words, akin to adjectives, called determiners. The definite

article is the and the indefinite article is a or an.

Audience

Audience means the kind of reader or listener the text was intended for. As this

is unlikely to be you, sadly you do need to attempt the near impossible and

'become' the intended reader. Always consider a text in this way or you will run

the risk of 'misreading' it. Also, avoid being overly specific or informal when

describing an audience’s likely characteristics: 'this writing is suitable for clever

so and so’s of about 23 and over' sounds rather less impressive than, 'the style

of this text seems geared towards an educated and sophisticated adult

audience'. For module 1 in your exam, audience is one way to categorise

similar texts.

Auxiliary verb

English verbs are limited as to what they can indicate alone, i.e. through their

own morphology. Morphological inflexions can be used, for example, to show

that an event occurred in the past (e.g. cooked) and in the present (e.g. cook);

they can also show third person agreement (e.g. she cooks) and continuous

action (e.g. cooking).

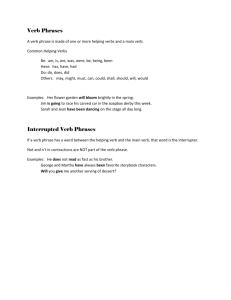

More often, the main verb needs to be linked with a secondary verb form which

accompanies it to create a verb phrase. These secondary verbs are called

auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs are used, for example, to give a sense of time to

the main verb (e.g. 'He will be working soon.') or to create a question, 'Have

you won?', 'Do you believe it?', 'Could it be true?'.

Common auxiliary verbs are forms of to be (is/am/was/are/were/will), to have

(has/had/have) and to do (does/did).

Some auxiliary verbs are used to indicate that an action is not real but simply

an idea or possibility. These are called modal auxiliaries, e.g. may, might,

would, could, should.

Clause

A clause is a key grammatical structure and this means that clauses are things

(clausal)

that you need to have, at the very least, a basic grasp of. Thought of at its

simplest, a clause can be considered as a short 'sentence' - one that occurs

either on its own (e.g. "I ate the jelly") or together with other clauses to make

a longer sentence (e.g. "because I was hungry").

A clause, then, is a group of words that is either a whole sentence or is

a part of a sentence.

Clauses are built up from individual words or from small clusters of

words called phrases.

Most clauses are built around a main verb which tells, often, of an

action, thought or state, e.g. "I ate the jelly because I was hungry".

A clause can be what is called independent. This mean it is acting as a simple

sentence, as in the example, "I ate the jelly". Independent clauses can also

exist as a part of a larger sentence when they are called not an "independent

clause" but a main clause.

Another common type of clause exists just to help out the meaning of a

main clause. This second kind of clause is, therefore, dependent on its main

clause for its meaning. An example would be the dependent clause,

"because I was hungry"; you'll see here that there is an extra word at the start

of the clause: "because". It is this extra word that stops the clause being able

to be independent or to be a main clause; the word "because" forces the clause

to be dependent on some other main clause, e.g. "I ate the jelly because I

was hungry". This words acts to subordinate its clause and so is called a

subordinator. Subordinators create dependent clauses - more often, these

days, called subordinate clauses (sometimes reduced to "sub-clauses").

There are many subordinators. Look at this example: "He hit him even though

he was a friend":

He hit him

even though he was his friend.

MAIN CLAUSE

DEPENDENT (subordinate) CLAUSE

An important kind of clause acts as if it were an adjective - it adds extra

information about a noun or noun phrase. These clauses are called relative or

adjectival clauses. They can seem confusing because they can be inserted

in between their main clause, e.g. "The girl who wore a red dress left

early." This sentence contains one main clause "The girl left early" and one

dependent or relative clause, "who wore a red dress".

The subordinator in this example, the word "who", is acting as a

pronoun (i.e. it is a word that takes the place of, and stands in for, a

noun). Here it is called, therefore, a relative pronoun because it

introduces a relative clause.

Other relative pronouns are "that" and "whom".

Sometimes the relative pronoun can be missed out to create an

elliptical relative clause, e.g. "The joke [that] he told was funny";

here the relative clause is "he told".

The structure of clauses is fairly fixed in English syntax (S = subject V

= verb O = object C = complement A = adverbial). In certain dialects and

in poetry the syntax can be varied and the sense still kept, e.g. "A ballad Alison

sang".

S+V: Alison / sang.

S+V+O: Alison / sang / a song.

S+V+C: Alison / is / a good singer.

S+V+A: Alison / sings / in the choir.

S+V+O+O: Alison / sang / her mum / a ballad.

S+V+O+A: Alison / sang / the song / from the song-book.

Cohesion

Many patterns of words exhibit a quality known as cohesion. This means that

(cohere / coherent

they form coherent units. Phrases are an important coherent grammatical

/ coherence)

unit. Words that cohere are cohesive: they appear to act not as individual

words but as a single unit, e.g. 'inside out', 'at three o'clock', 'the awful

creature', 'has been eating', 'in a traditional manner'. These examples of

coherent groups are all phrases, but clauses, sentences and discourses

are also, if they are to be effective in communicating ideas and facts,

coherent.

At the level of discourse, the reader or listener also needs to be able to link the

different sentences and paragraphs (or stanzas in a poem, etc) in a logical way.

This is achieved by many linguistic means including graphology, semantics,

pragmatics, narrative structure, tone, lists, pronouns, proper nouns,

repetition of either logical or similar ideas, use of synonyms, and so on. The

analysis of the cohesive qualities (i.e. the coherence) of a text is the analysis of

discourse structure.

Collocation

Many words are habitually put together - or collocated. A collocation is any

(collocates /

habitually linked group of words - a kind of lexical partnership, e.g. 'fish and

collocated)

chips', 'salt and pepper', 'don't mention it', 'it's nothing...', 'Oh well!', 'bangers

and mash'... and so on. Many idioms or idiomatic phrases exhibit

collocation, e.g. in a jiffy.

Colloquial / slang

A 'colloquy' is a formal word for 'conversation', so colloquial language means

(colloquialism)

the everyday language or register we adopt when chatting to friends, for

example, e.g. 'Hello Fred, how's the new mother-in-law these days?'.

Slang is a particular form of colloquial language used by certain social groups,

e.g. 'Hey-up Fred! How's the new battle-axe then?'; 'Hey that's some cool dude

there!'

Complement

A word, phrase or clause that follows a verb and which simply adds further

information concerning, usually, the verb's subject. Complements usually follow

stative verbs such as 'to be' to create a statement (i.e. a declarative

sentence), e.g. 'He is happy'. Here the adjective 'happy' is the subject

complement. However, in the sentence, 'He made me happy', the adjective

happy is called an object complement as it gives more information about the

verb's object, me.

Conjunction

A word used to link words, phrases and clauses. Common conjunctions are and,

but, or, either... or, neither...nor. These can link 'equal units' such as words,

phrases or main clauses. A special kind of conjunction that can link 'unequal'

independent and dependent clauses is called a subordinating conjunction.

There are many of these, e.g. if, when, where, unless, etc. Also see sentence

and clause.

Connotation /

The denotation of a word is its direct, literal or specific meaning (as can be

denotation

found in a dictionary). If a word also has implied or associated meanings when

(connote /

used in a certain way, these are called the word's connotations. The word

connotative denote

'bat' in this sentence is being used with its denotation: 'A bat is a flying

/ denotative)

mammal.' however, the word, 'bat' can also take on extra meanings, often

metaphorical, e.g. 'He went like a bat out of hell'.

Interestingly, the word 'bat' also happens to have several possible denotations:

'a cricket bat', 'a vampire bat', 'They bat next' (as well as other slang and

dialect meanings): words that have several denotations are called polysemic.

Polysemy is an area of semantics and pragmatics.

Context

Context is always an important aspect to consider whenever you analyse a

(contextual /

text. Context refers to those particular elements of the situation within which

contextualise)

the text is created and interpreted that in some way or another affect it (for

example, the effects of time, place, ideology, social hierarchies, relationships,

etc.).

Importantly, language has two potentially important contextual aspects: the

context in which it was created and that in which it was interpreted. For

example, a letter from a manager to one of his staff will be affected by context

such as the situation itself, the power relationship that exists between the

manager and the worker, the historical conditions and so on. Another example,

when you speak to your parents or when you speak to a friend on the phone

you will see that context naturally affects the linguistic choices - the style - of

the discourse in important ways. Also see register.

Copula / linking

Verbs that act to link a subject to a complement, for example, the verb 'is' in,

verb

'The rabbit is soft and furry', are called 'copulas' or 'linking verbs'.

Determiner

One of a small group of words - a word class - that precedes and premodifies a noun and creates a noun phrase, e.g. a, the, some, this, that,

those, each.

Determiners include the three 'articles' (i.e. a, an, the) and similar

words: e.g. some, those, many, their. Each of these are said to

determine the number or 'definiteness' of their noun, e.g. 'That man is

the one!'

Confusingly, determiners can themselves be pre-modified by 'pre-determiners',

e.g. 'Even the apples were rotten' 'All the books were lost.'

Discourse /

Whenever we use language for any purpose we create a discourse. What we

discourse analysis

are doing when we enter into a discourse is to try to express to someone else

/ discourse

some of our thoughts, ideas and (whether on the surface or implied) feelings.

structure /

These thoughts will have arisen as a reaction of our mind to the context in

discourse

which it finds itself. Texts - discourses - arise from an individual's context.

community /

Sometimes this context will involve communication with a known person,

discourse

sometimes with a group or audience, sometimes with an unknown individual or

communities

group. Conversation and letter writing are examples of the former, drama and

media texts of the latter.

We have evolved into very sophisticated communicators; and of course we

know how to use more than just language to create our discourse: we use

language and paralanguage (non verbal features) as well as kinesics (body

language). This all combines to make discourse a subtle, sophisticated and

complex area of study. But, even a basic understanding of discourse can help

push your marks up to the highest bands.

Aspects of communication that affect discourses include genre, context,

audience and purpose ('G-CAP'). All of these, and especially the first three,

will act to affect our language choices, often to 'constraint' what we can say or

write. 'Freedom' of speech is an illusion! Context is an especially important

aspect of discourse analysis as the social and hierarchical aspects of life often

bring all kinds of pragmatic meanings into the discourse.

A discourse occurs whenever we put thought into language. This could be for a

whole range of reasons - we might be in a conversation, writing a novel,

producing a piece of homework, holing someone to ransom, texting a friend...

all kinds of reasons. The result of this 'conversion' of thought and ideas into

language is the production of a discourse between the parties involved. And

these discourses can ne productively analysed as an analysis at the level of

discourse will reveal many interesting and subtle areas of language use.

Discourse, therefore, is no more than language - a kind of 'text' - but

considered as a part of the original context of its use. When considering

discourse, therefore, you need to consider all of the important aspects of

context that affected either its creation, its reception or its interpretation.

And remember that discourses or spoken - planned, spontaneous, to a known

audience, an unknown audience, historical, etc..

Thus, everyday language, technical language, business language, children's

language, cookery-book language, newspaper language... any and all kinds of

language, can all be considered at the level of discourse. All texts will contain

within them some discernible aspects of their user's personal, cultural, social

and historical situation. Discourse analysis comments on these contextual

aspects.

Commenting on the situation in which a discourse arises means taking

account of aspects of both its local and ideological or cultural

context.

When analysing a text, it can be fascinating (and gain many extra marks

because of its subtlety) to dig deeper than the surface meaning of the words to

try to reveal interesting contextual aspects of the text's users. To make this

clearer, you can imagine that our own society is far more liberal-minded than,

say, the society of a century ago. This aspect will show up in the texts written

in these periods through a variety of aspects including word choice and

grammar. Similarly, aspects of social hierarchy and social power always

manifest themselves within texts. Imagine a conversation between a patient

and a doctor, for example - again, discourse analysis seeks to reveal this.

We can, somewhat artificially perhaps, but useful, 'lump together' certain

discourses and see that they contain broadly similar elements because of the

context, for example, in which they occur. Thus the idea of a 'discourse

community' or discourse communities can be used, similar to the idea of a

'register'. Young people, to take an example, tend to use language that shares

many similar features, and they can be called a 'discourse community'. In this

instance, this is similar to the idea of sociolect, also - but not all discourse

communities share a sociolect.

An important part of discourse analysis is to determine what are called the

orders of discourse. In any discourse, it is clear that speakers or readers are

rarely 'on equal terms'. Usually there is a hierarchy of power or a power

relationship involved, wherein one participant - through language choices can 'position' the other participant in a less powerful position. An analysis of

men and women in conversation has revealed many ways in which apparently

innocent uses of language create a power relationship between the participants.

'Frameworks' are recommended by most exam boards to help you to analyse

discourse. The basic aspects of a discourse are lexis and grammar; but

meaning can be signified directly ('semantically') or through implication

('pragmatically'); the form of language is also important (graphologically

and phonologically); and the discourse structure is crucial (see below).

Thus you can use frameworks to analyse discourse effectively.

Discourse structure can be a useful part of discourse analysis and is

generally rewarded highly in your exams. Analysing a text at the level of its

discourse structure sets out to reveal the various methods used, effects

created and purposes intended by the language user to create a coherent

and unified stretch of language. A text aimed at a child, for example, will have

a much more obvious structure with clear 'linguistic signposts' to guide the

child through it. If you compare such a text with, say, a broadsheet newspaper

article, you will immediately notice that the means of linking ideas in the latter

will be far more complex, sophisticated and subtle. Discourse structure,

therefore, is one of the elements of style: those choices a language user makes

to suit context, genre, audience and purpose.

Element

An element is a distinct grammatical unit - a 'building block' or segment of a

sentence there are three important grammatical elements: word, phrase and

clause. Some of the elements of a discourse or text are their sentences,

paragraphs, chapters and so on.

Elision

Elision is the omission of one or more sounds from a word, e.g. a vowel,

(to elide)

consonant or a whole syllable. It is used to create a word or phrase that is

easier or more casual to suit an informal context, for example, e.g. the word

'comfortable' is usually elided when spoken.

Ellipsis

Grammar allows some words to be missed from a grammatical construction

(elliptical)

(i.e. for sentences to be grammatically abbreviated) and yet for the sentence

still to be meaningful, e.g. 'I bought half a dozen eggs and [...I also bought...]

six rashers of bacon.' The reader or listener is able to 'add back in' the

elements that have been left out and thus understand what is meant.

Ephemeral

A term that means 'lasting for a short time', i.e. transitory. In the study of

language change, it refers to fashionable words that drift in and out of fashion.

Speech is often considered to be an ephemeral thing in contrast to the more

permanent nature of writing.

Finite / non finite

This word applies only to certain verbs. A verb in a sentence can exist on its

own as in these examples: 'It's good to exercise' or 'I enjoy exercising'. In each

of these sentences, the form of the verb is termed non-finite.

Alternatively - and every complete grammatical sentence has one at least by

definition - the verb can be made finite. This simply means that it is 'attached'

grammatically to a subject word. This subject is usually either a noun or

noun phrase. Look at this example: I exercise to keep fit'). In this latter case

the subject/verb combination work together to create a clause.

Form and content

Form means the sound, shape and appearance of something, e.g. two forms of

the word please, are pleases and pleased. The form of the sentence, e.g. 'He

pleased himself.' can be explained by referring to two kinds of structure: that

of its individual words (i.e. their morphology) and the way its words relate to

each other (i.e. their syntax). The study of both of these aspects of sentences

is called grammar the study of the form of a text is called discourse

analysis.

The content is the meaning contained by a word, phrase, clause or sentence

and this is involved with its function. The separation of form, function and

content is a theoretical way of discussing the effect of each even though all

three are inextricably linked.

Function

The function of a word is what it 'does' in its sentence, e.g. its function is to

act as a subject, object, verb, etc. The function of a sentence is what it is

intended to 'do', e.g. to make a statement, ask a question or give a command

or order.

Genre

Genre is a way of categorising texts according to similarities they share with

(generic)

those we already know. More generally, genre is a way of making the

unfamiliar seem more familiar and hence, be more easily and quickly

recognisable. New things might be unwanted, uncomfortable or even

threatening. For instance, if we see an insect that looks different from a wasp

but has black and yellow stripes and a pointy body – 'genre' allows us to

quickly label it and either run, squash or collect it. Genre is a kind of 'survival

instinct'. The world is naturally (sometimes worryingly and even threateningly)

chaotic things can and do happen at random – even dangerous things. To feel

safe, we force order upon as much of the world as we can: we build houses,

store food, name things and so on. We must feel secure. Your bedroom might

not seem to reflect your instinctive ordering mentality, but it most certainly

does: firstly, it is a defined space (it is a piece of the world that is more secure

because it is contained) and, although your belongings may look like pure

chaos to an untrained observer such as mum and dad, you know precisely what

is in that heap of clothes, CDs, magazines, English Language homework and

whatever else.

What has this to do with language study? Well, surprisingly, we impose order

and give labels even to things as unthreatening as language and media texts

(you wouldn’t want a romantic film to turn into 'The Chain Saw Massacre'). So,

texts that share content (e.g. chain saws, fondling couples), function (e.g. to

frighten, to arouse), and form (e.g. books, films) are categorised and 'made

safe'. But because, as they say, familiarity breeds contempt, genres can and do

change – but slowly (see Pulp Fiction or Reservoir Dogs for evidence).

Genre is an important idea because it affects the production as well as the

reception of texts. Writers know what we expect from a particular genre, and –

to keep us receptive and comfortable (and hence – importantly for language

study – more easily influenced or persuaded) – they will stay broadly within a

particular genre’s expectations. Typical genres of fiction are adventure,

detective and horror, and of non-fiction, reports (e.g. newspaper, school),

biographical writing, advertising, recipes, etc. Taking account of genre allows

you to comment on effective genre indicators ('signifiers') and stylistic devices

within a text. Of course, genre is an ideal way of categorising similar texts.

Grammar

Grammar is the set of rules that tells how words can be put into a sequence

(grammatical /

and a form that allows their meaning to become unambiguous in a sentence.

grammaticality)

The order of words in a phrase, clause or sentence is called its syntax and the

form of words is called morphology (for example, to show plural we add the

morpheme s, to show possession, we add the morpheme 's).

Graphology

Graphology is easily misunderstood and many teachers advise students to pay

(graphological)

it little attention as it can lead to analysing the images and diagrams in a text a habit that loses many marks in a language exam. But it needn't be that way

at all as, properly applied, a graphological analysis can be very useful and

subtle.

Originally, graphology applied only to the appearance of a person's

handwriting; for your course, however, it applies to any aspect of the form

and appearance of a text that modifies meaning in any way.

It is the graphological qualities of any written or printed text

that we first notice.

This means you would do well to consider analysing a text at the level of

its graphology before looking at other methods of analysis such as

lexis or grammar. The graphological features of a text determine subtle and

important aspects such as genre and ideology: how we react to the text itself.

Graphological features, therefore, carry pragmatic force and are an important

part of our society's discourse.

For example, a text's layout, presentation, use of paragraphs, lists, 'bullets',

font choices, underlining, italics, white space, colour, etc. can all create

different kinds of impact, some of which will cause the reader to react

differently for example, graphological aspects can create important pragmatic

perceptions of power and influence.

Head / head word

All phrases have what is called a head or head word. This is the word within

the phrase that determines its grammatical function (and which acts to provide

its most general meaning); other words within the phrase act in a modifying

capacity. For example, in the noun phrase 'the old-fashioned door', the head

word is the noun, door - the remaining words within the phrase act to modify

this head word; in a verb phrase such as 'might be hit', the head word is the

finite verb hit and in a prepositional phrase such as 'on the table', the head

word is on.

Ideology

Ideology refers to the values and attitudes we all share towards such things

(ideological)

as ourselves, others and institutions. Ideologies are general or cultural

ways of thinking that form the foundation of the many important 'belief

systems' that are adhered to by groups or whole societies. They form a

society's and individual's 'world view' or 'mind set' concerning how things are

and ought to be. A society is a group of people who share certain key values

and ideas; these values and ideas are called that society's ideologies.

Texts are created by speakers and writers who share society's beliefs

concerning 'what is right' and 'what is wrong' or about 'the way things should

be for the best' in society. These ideologies mw be 'hidden' because they seem

'natural' or 'common sense', as the result of 'progress' in our 'advanced'

society, and so on.

If we closely examine and consider some important ideologies, it can be seen

that those ideas act to reinforce the structure of our society. Some

thinkers - called Marxists - conclude that this might not be a healthy thing for

a society as it helps maintain what they call society's status quo - ideas that

maintain the existing social hierarchies and power structures (with, for

example, the wealthy holding the reigns of power, and the poor being attached

in important ways to those reigns, perhaps?).

This 'political' way of considering the effect of ideologies arose in the theories of

the key nineteenth century philosopher, Karl Marx. Marx recognised that those

with power naturally enough wish to hold on to their status (those who 'own

the means of production', i.e. the powerful, he called the bourgeoisie lesser

mortals are the proletariat or the masses). Marx thought that the bourgeoisie

were able to create and reinforce particular 'ways of thinking' that would act to

reinforce and maintain a society’s status quo and hence, existing hierarchies of

status and power.

Ideas that 'maintain the status quo' are referred to as a society’s dominant or

prevailing ideologies. An example of such an idea might be, 'He deserves to

be rich because he’s worked hard for all he has' but this ignores the plight of

millions who work even harder but stay poor. The point of ideological thinking

is just that – it ignores, hides, sidelines, and 'disappears' those groups whose

ideas it does not support.

Marx felt that such ways of thinking act not only to keep the powerful in power

but also to create the conditions necessary for the masses to justify their own

lower position in society. The means by which ideas can support the status quo

is called hegemony. Prevailing ideologies become a part of us as we grow up

we become 'conditioned' into thinking that the way our society operates is for

the best. This 'social conditioning' is created through the family, school,

religion, law and – very importantly for language study – the mass media

indeed, the media receive much of the focus of Marxist criticism because it is

considered a major means through which powerful elite groups can increase

their hegemony over others. It is hegemony that causes us to view our

capitalist, consumerist 'social-democracy', with its hierarchies of status and

power, its elitism, its individualistic self-centredness, its poverties and its

suffering… as 'the best of all possible worlds'.

In studying a text for its hegemonic or ideological power, you must learn to

look for what is termed 'ideologically loaded' language. Such language is that

which has judgemental value as well as meaning. Look out for such language

and consider its seductively persuasive effect as it subtly 'ideologically

positions' you as reader. Many ideologically loaded words have their judgmental

value because their meaning is relational: they exist as 'binary pairs', e.g.

'master/mistress', 'housewife/working mother', 'middle class/working class',

'freedom fighter/terrorist', 'hero/coward', 'normal/abnormal', 'gay/hetero',

'feminine/feminist, 'The West/the East', etc. Some linguists maintain that all

language – all meaning – is an 'ideological construct'.

CLICK HERE if you need more help.

Idiomatic language

Idiomatic language refers to many words or phrases that are a familiar and

(idiom / idiomatic

everyday feature of our language. Idioms are a part of the comfortable,

phrase)

conversational style of language we use daily - but to a foreigner, idioms are

difficult to understand because their meaning is very different from the literal

meaning of the words that make them up, e.g. 'He wants his pound of flesh.'

'You scratch my back, I'll scratch yours' 'That's real cool' 'No way, José', 'He's a

pain in the neck!', etc. Each of these are idioms - or idiomatic phrases. You will

notice that idioms always exist as fixed collocations which do not work if the

phrase order is altered at all. For example, we cannot really say, 'He scratched

my back and I scratched his...'.

Imagery

Words can be chosen to create more than just meaning: they create feeling,

too. Some words or phrases are able to create a particularly vivid mental sense

of a picture, person, sound, taste, etc. This effect is called imagery. Imagery is

a very important feature of all descriptive writing and, especially, of poetry. The

most common way by which a writer can create imagery is through the use of

figurative or metaphorical language, typically through the use of

metaphor, simile and personification. Truly effective imagery acts almost to

etch itself onto the reader's mind. This can be a very emotional and persuasive

device as it acts to engage the reader intensely in the subject matter of the

writing.

Imperative

A command sentence which uses the second person plural form of a verb but

misses out the subject pronoun 'you'. It gives orders, e.g. Leave now! Sit

down.

Infinitive

A form of a verb without tense and often introduced by 'to' infinitive forms can

replace noun phrases as subject or object of a verb, e.g. Object: He likes to

eat subject: To fish is a very relaxing way to spend the morning.

Inflection

The way words can change their form to show, for example, that they are

(inflexion / inflect

singular or plural (e.g. table becomes tables) and to indicate tense (e.g. change

/ inflects /

becomes changes/ changed/ changing) or possession (The cat's whiskers).

inflected)

Intensifier

Intensifiers are a special kind of adverb. An intensifier is used when the

semantic value of another adverb or adjective needs to be altered. Examples of

intensifiers are: very, quite, absolutely and extremely but there are many

more.

Intensifiers act to pre-modify their adverb or adjective. Can you identify the

intensifier in this sentence: 'It's a terrifically bad accident.'?

Interjection

A word class that is used to show emotion, e.g. 'Ouch!', 'Hey!'

Intransitive

A verb is called intransitive when no action transfers from their subject to an

object, e.g. we swam like a fish they sang beautifully he died. A transitive

verb always takes an object - the thing that takes its action, e.g. He hit his

thumb with the hammer.

Irony

Irony is the name given to the effect of meaning created when one thing is

said or written but another - sometimes opposite - thing is meant. In speech

this effect is created by tone of voice in writing by carefully chosen lexis. The

study of such meaning falls within the area known as pragmatics.

Latinate

This term refers to those many rather formal words in English that derive from

either Latin or French. These words entered the language most notably during

the period following the Norman Conquest (1066). King William I spoke a

northern French dialect that itself was heavily influenced by the classical Latin

language of ancient Rome; he insisted that the nobility of newly conquered

England learn to speak French and, from this, many French/Latin words

entered the language. The Latinate equivalent now sits alongside the original

Old English/Anglo-Saxon term and tends to be used in more formal occasions.

Examples are motherly (Anglo-Saxon)/maternal (Latinate); inn (AngloSaxon)/hotel (Latinate). As a rule of thumb, if you can pronounce the word in a

French accent it is Latinate! A text that relies heavily on Latinate words will be

aimed at a more educated audience.

Lexeme

A lexeme or lexical item is a word - or occasionally phrase - in its most basic

(lexical item /

form, like the head words found in a dictionary that are listed each as

lexemic / lexicon)

separate entries. An example is the word 'spell'; from this lexeme there can be

several derivations, e.g. spelled, spelt, spelling, etc. These inflected forms of

the root word are not counted as lexemes. The word 'crane', as an example, is

two lexemes, one meaning a large bird and the other a machine for lifting.

Also included under the heading of lexemes are the so-called phrasal verbs;

these are short phrases whose meanings are different from their constituent

lexemes, e.g. 'see to', 'break down', 'put up with', 'wind up'.

Idiomatic phrases that carry meaning as a unit are also counted as lexemes,

e.g. 'give over, 'rain cats and dogs', etc.

The collection of lexemes that forms a person's vocabulary is called his or her

lexicon. A dictionary is another kind of lexicon.

Lexical (dynamic)

Lexical or dynamic verbs tell of an action (to hit, to call, to sing); stative

and stative verbs

verbs tell of a state of being (to be - am, is, was, were - to think, hope, seem,

appear, feel, etc.).

Lexis

Lexis means the vocabulary of a language as opposed to other aspects such

(lexical)

as the grammar of the text. Lexis is clearly an important aspect of creating a

suitable style or register (i.e. when choosing language and language features

to suit a particular genre, context, audience and purpose).

Lexis and semantics are very close and often used interchangeably.

Lexical cohesion occurs when words have an affinity for each other as in

collocations.

Linguistic

Referring to the study or ways of language and the use of words to create

meaning.

Modifier /

Modification describes the grammatical process through which the meaning of

Modification /

a head word within a phrase can be altered, refined or modified. This is done

Pre-modification /

by the addition of one or more words. The result of the modification of a word

Post-modification

is the creation of a phrase e.g. in the noun phrase, 'A criminal act', the head

word (the noun 'act') is modified by the noun 'criminal'.

Nouns can be both pre-modified (by linking with one or more adjectives, e.g.

A tall dark stranger' or with other nouns, e.g. 'oven glove') as well as postmodified, e.g. 'The man with an ice-cream. Prepositional phrases can also act

as modifiers when they act as the complement of a verb, as in, 'He's in a

mess'.

Mode

'Mode' refers to the channel of communication of a text. A text might be

spoken or written, for example, or it might show features of being 'mixed

mode' is the sense that it contains features of both speech and writing, as in

text messages and email.

Mood

'Mood' is an aspect of English verbs. Verb phrases can be categorised

(modal / modality)

according to whether they express an actual or a potential action or state. The

moods are: indicative mood: 'He plays well'; 'She is happy' (indicating an

actual event or state); imperative mood: 'Sit down!' (issuing a command);

interrogative mood: 'Will you please sit down?' (asking a question);

subjunctive mood: 'If she were alive, then...' (pointing to a possibility or

wish).

Mood is often created in a verb phrase through the use of a modal auxiliary.

This kind of auxiliary verb usually creates the effect of suggesting that the

action told of by the verb is not real but is potential.

Morphology /

The suffix "morph-" is to do with shape, and morphology concerns the form and

morpheme

shape of words. It is an important aspect of grammar (along with syntax);

(morphological)

morphology is the study of the way words are formed. The smallest part of a

word that can exist alone or which can change a word's meaning or function is

called a morpheme (e.g. un-, happy, -ness).

A bound morpheme is an affix, i.e. usually a prefix or a suffix, e.g. un-, tion. These are 'bound' called because they must be attached to another

morpheme to create a word. Morphemes that can exist alone as a complete

word are called free morphemes, e.g. happy.

Narrative & Myth

Whilst it's true to say that a narrative is no more than a story, the important

realisation from an analytical viewpoint is that when we tell or write a story,

we all tend to use a very similar form and structure, no matter what the

story and whether it is imaginary or not. Narrative is easily one of the most

common varieties of social discourse and a day will not pass without you

reading or hearing a story - or constructing one of your own.

In a narrative, events (whether they be real or fictional) are told in certain

ways: they are told ('narrated') from a certain point of view (e.g. 'first

person', 'third person', 'multiple viewpoint', etc.), they are carefully selected

for their value in creating a sense of involvement, interest and tension; the

events are unified and coherent, they have an apparently logical 'cause and

effect' structure. The events typically involve a main character (called, 'the

protagonist' or 'hero'); the life of the protagonist is usually disturbed from an

initial - or presumed - state of 'normality' or equilibrium; this disturbance is

created by a conflict that is introduced by a second character (called the

'antagonist' or 'villain' - also sometimes a social institution); the conflict is

tackled by the 'hero' during the development or rising action of the

narrative; this leads to a climax of action followed by a winding down and

tying up of loose ends called the d�nouement; during this final part of the

story, there is the formation of a new equilibrium and a final resolution.

Typically, by the end of the narrative, the protagonist's life will have changed

in some way and he or she will have learned something useful about life.

From early childhood, we become accustomed to making sense of the complex

events of the world through the simplifying and satisfying means of narrative,

not noticing the way the form and structure of narrative orders and simplifies

reality, most particularly the way it positions people as either wholly 'good' (=

heroes and helpers) or wholly 'bad' (= villains and accomplices). The fact that

this is merely a point of view and a massive over-simplification of the realities

of life passes us by as we become absorbed by and relate to the characters

and events of the narrative. It has been suggested that we might even be

born with such basic structures and forms embedded within our subconscious;

they certainly have an enduring and unshakeable impact upon our psychology.

Certainly, it is clear that as human beings we do have a need for security,

control and order within our lives and narrative, along with genre, are two

very important means by which order and security can be created in what is,

in reality, a disordered and even potentially dangerous universe.

Many narratives are so ancient and enduring that they are called myths.

Examples are the romance myth, the family myth, the hero myth and so on.

Narratives usually have a relatively fixed structure: a 'beginning' (where a

setting creates mood or atmosphere and characters are introduced), linked to

a 'middle' (where the hero meets a problem and works to overcome the

problem and where the plot becomes interesting and reaches a climax) linked

to an 'end' (where a satisfying sense of closure is introduced - the plot draws

to a conclusion).

Nonce word

'Nonce' is an archaic word meaning, 'for the one time'. A 'nonce word' is a

word that is coined for a particular occasion. Nonce words sometimes catch on

and enter everyday usage, initially as neologisms or new words - they are

especially common in pop culture, e.g. 'poptastic'; Linguist David Crystal

mentions the word 'floodle' someone once used to mean a stretch of water

bigger than a puddle but smaller than s flood.

Noun

A noun is any word that can form the head word in a noun phrase or be the

(nominative)

subject or object of a verb. Semantically speaking, a noun is any word that

'labels' or 'names' a person, thing or idea.

There are several types of noun: common noun (e.g. computer, sandwich,

cats), proper noun (proper nouns are names for individual nouns, e.g. Coke,

London, Simon), abstract noun (abstract nouns are 'ideas', e.g. death,

hunger, beauty), concrete nouns (concrete nouns are solid objects in the

real or imaginary world, e.g. bread, butter, clock) collective nouns

(collective nouns name groups of individual or things, e.g. parliament,

audience collective nouns are often treated as if they were singular, e.g. 'The

choir is singing well.'), mass (or non-count) nouns (mass nouns exist as an

undifferentiated mass, e.g. card, beer, milk, cake), and count nouns (count

nouns exits as countable items, e.g. bottle, pencil).

Orthography

Orthography is the term used in linguistics used to refer to the way that words

(orthographic)

are spelled.

Participle

Words made from verbs that are used either with an auxiliary to create a verb

(participial)

tense (e.g. was eaten) or as an adjective to describe a noun (e.g. an eating

apple) or as a noun to label a thing (e.g. the singing was loud). Notice that

because the participles all derive from verbs, they always retain the idea of

action in their meaning.

Person

This term is used to describe pronouns. A pronoun always has a referent

(i.e. a noun to which it refers). The referent of 'I' is always the writer or

speaker of a sentence and is referred to as the first person singular

pronoun 'we' is called the first person plural pronoun the person or people

spoken to is referred to as the second person pronoun, i.e. 'you' (both

singular and plural) the person or people spoken about is referred to as the

third person pronoun, i.e. he / she / it (third person singular) or they

(third person plural).

Phonetics

Phonetics is the study of the way people physical produce and perceive the

Phonology

different sounds we use to create speech. These sounds are called phonemes

Prosody

and are created by the various 'organs of speech' in the body, including the

Phoneme

tongue, the soft and hard palate, lips, pharynx, etc. Phonetics, unlike

(phonemic)Diphtho

phonology, is not concerned in any way with the meaning connected to these

ng

sounds.

Glide

Phonology is the study of the way speech sounds are structured and

how these are combined to create meaning in words, phrases and

sentences. Phonology can be considered an aspect of grammar and, just as

there are grammar 'rules' that apply to the syntax of a sentence and the

morphology of words, there are phonological rules, too.

Even in very early childhood, children are said to be able to produce (i.e. they

can articulate) the full range of sounds needed to create all of the words used

in any world language, yet as language acquisition progresses, those

phonemes that do not apply to their mother tongue become forgotten. This is

so much so that in later life, if a second language is then attempted, the

pronunciation of non-English phonemes needs to be re-learned - this time at a

wholly conscious level, as opposed to the ability to pronounce each English

phoneme without any conscious thought. Even 'non-words' such as 'erm',

'uh?', etc. use English phonemes.

An important part of phonology is the study of those sounds that form distinct

units within a language. The smallest unit of sound that can, in itself, alter the

meaning of a word is called a phoneme. Although there are 26 letters in the

English alphabet, it's interesting to note that there are around 44 phonemes in

the dialect called Standard English. This means that letters cannot represent

phonemes as such and so other symbols are used. Each phoneme is given a

symbol so that the accurate pronunciation of any English word can be

represented in writing. Here is the (American) English phonetic alphabet version of the International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA:

The extra sounds we have above the number of letters we have available in

part explains the complexities of English spelling (see orthography). Consider

the word might, in which there are three phonemes m-ight-t (represented as

m/ai/t using the Phonetic Alphabet), changing just a single phoneme can

completely change the meaning of this word, e.g. mate, m-a-te (represented

as m/ei/t phonetically).

Some of the extra sounds are there because we use phonemes that are called

diphthongs. If the tongue has to move significantly to make a vowel sound,

the result is a diphthong; it sounds like a rapid blend of two vowel sounds.

The letter 'i' in the word 'kite' is a diphthong - it is a rapidly made blend of an

'a' and an 'i' sound. The movement of sound from the 'a' to the 'i' is called a

glide.

Phonology also covers the study of important sound features such as

rhythm, pitch, tone, melody, stress and intonation. These phonological

features of language are aspects of prosody - they are referred to as the

prosodic or suprasegmental features of language.

Phrase

A phrase is a key grammatical unit. In terms of its meaning, a phrase

(phrasal)

expresses one complete element of a proposition. It will be made up of

one or more words and occupy a particular syntactic slot within its clause or

sentence, e.g. as subject, predicate or object. A useful rough and ready 'test'

for a phrase is that it can be 'replaced' in its clause or sentence by a single

word that is roughly its equivalent. Thus in the sentence, 'That old guy over

there has been patiently waiting for three and a half hours already', the noun

phrase, 'The tall man over there' could be replaced by 'he'; the verb phrase

'has been patiently waiting' could be replaced by 'waited', the prepositional

phrase 'for three and a half hours' could be replaced by 'ages'!

A phrase acts as a unit with individual meaning, but without

sufficiently completeness to be a clause or sentence by itself.

Noun phrase

A noun phrase always has a noun as its

head word, e.g. "a cat"; "the naughty

cat"; "that furry black mangy old cat".

Verb phrase

A verb phrase always has a verb as its

(sometimes called a head word, "drink"; "has drunk"; "has

verb chain)

been drinking"; "seems"; "will be";

"might have been"; "explained"; "has

been explaining".

Adjective phrase (or An adjective phrase always has an

adjectival phrase)

adjective as its head word, e.g. "gory",

"absolutely foul".

Adverb phrase (or

A phrase with an adverb as its head word,

adverbial phrase)

e.g. soundly; too evidently; as quickly

as possible

Prepositional

A phrase which has been constructed from

phrase (a special

a preposition with a noun phrase linked

kind of adverbial

to it to form a single unit of meaning, e.g.

phrase)

"up the road"; "across the street"; "round

the bend".

Phrases - with words - are the basic building blocks of clauses and

sentences. A phrase can always be split into two parts: its head word which

is linked to some kind of modification of the head word. The head word is

the central part of the phrase and the remaining words act to modify this

head word in some way, e.g. "The peculiarly strong creature" - can you see

that the head word of this noun phrase is the noun, "creature"?

As suggested above, a phrase does, in fact, act just like an individual word.

The next example sentence contains three phrases and a single main clause.

Can you recognise which are the phrases and which is the clause?

In a frenzy, without thinking, he grabbed him by the neck.

You might like to think that, between each word of the three phrases above,

there exists a kind of 'word glue' that gives the phrase its coherent quality.

The phrases "In a frenzy", "without thinking" and "by the neck" all can be seen

to exist as individual units of meaning, i.e. as individual phrases.

Notice that the clause in the above sentence cannot be called a phrase

because it is built around a verb (i.e. a verb phrase), "he grabbed

him"

Pragmatics

Pragmatics is an aspect of how language generates meaning - and as such, it

(pragmatic)

falls under the 'umbrella' of semantics, which is the study of meaning.

Semantics is often, simplistically, said to be the the study of surface 'sentence

meaning' and pragmatics to be the study of the deeper, inferred 'social force'

of language.

The clearest way we can communicate our ideas and thoughts is through

language. To achieve this, the ideas and thoughts we want to communicate

become 'encoded' either phonologically (by the sound of spoken words) or

graphically (through marks on a handwritten or printed page). When this

meaning is conveyed semantically, the encoded meaning - the words, phrases

and sentences we create - can be easily de-coded without particular thought

of the context. Sometimes, however, a deeper, inferred meaning is also

encoded within language, and this creates a pragmatic force within the text.

Thus, pragmatics operates whenever we write or say one thing semantically

but mean to infer extra force to our text or utterance.

Pragmatics is an absolutely key aspect of any A-level textual analysis

as it is so very revealing of important linguistic aspects.

If you ignore the pragmatic force of language in your analyses, you will

lose many marks.

An example will make this clearer. If you think about the phrase, 'Give him

one!', the meaning this contains will very much depend upon the social

situation in which it is used. It is the noun 'one' that, in certain social

situations, will carry different levels of force: it is a pragmatically loaded

word, where its precise meaning can only be inferred by the context of the

language use.

Pragmatic meanings can be inferred in this way because, owing to the

context of the language use, we are able to 'read into' a word the extra

meaning - the utterance's pragmatic force - conferred on it by the

way it is used within a particular social situation.

Pragmatics can allow language to be used in interesting and social ways:

knowing that your listener or reader shares certain knowledge with you allows

your conversation to be more personal, lively or less extended. It also allows

you to use words and give them inferred elements such as power aspects,

because your listener is aware of your social standing, for example. Similarly,

language can act in ideological ways to reinforce a society's values - again,

pragmatically. At another level, language users can rely on pragmatics to help

them cut down on the number of words needed to make meaning clear - and

hence contributes to a more lively style.

Here are a few examples that require more than a semantic analysis to reveal

the intended meaning of the text's words and phrases, but where the

pragmatic meaning is perfectly clear:

'BABY SALE - GOING CHEAP' (poster seen in shop window - but no

babies are for sale).

'Quick! Fire!' (and you know you must run).

'Pass the salt' (and you know it's not an order).

'Are you going into town?' (and you know it's a request for the

person to come with you).

'He's got a knife!' (and you don't ask how sharp it is)

'I promise to be good.' (and you don't expect a repeat of the bad

deed).

'The present King of England is bald.' (said on TV, yet you can work

out what is meant even though we have a queen).

'Another pint...?' (and you know you've already had one).

'I said, 'Now!'' (and you know when).

'Gosh - it's cold in here!' (and someone shuts the door or window).

An important area of pragmatics is in the study of language and power. The

implicit understanding of a power relationship between, say, two speakers, is

often indicated by the meanings implied by the language used. This meaning

can be very context dependent.

Predicate

The predicate is all that is written or said in a sentence or clause about its

grammatical subject, e.g. The young choir boy [subject] sang every song in

the book [predicate].

Prefix

A prefix is a type of affix (i.e. a bound morpheme) that is added to the

beginning of a word to change its grammatical function or meaning (e.g.

un+happy) - see suffix.

Preposition

A small word or phrase that begins a longer adverbial phrase (called the

(prepositional)

object of the preposition) that acts to tell about place, time or manner and

relate this aspect to some other word in the sentence, e.g. in, on, by, ahead

of, near.

Progressive /

A verb form created from the present (i.e. -ing) participle to tell of a

continuous

continuing event, e.g. he is laughing his socks off.

Pronoun

A word used often - but not always - to replace a noun, e.g. Alex, when the

teacher came into the classroom, you mean you really didn't see her? See also

person.

Purpose

Purpose is the reason why a text was created. This may be, for example, to

entertain, explain, instruct, persuade or inform. The purpose of a text is its

writer or speaker's controlling idea: the message they wish the text to leave

with the reader or listener. When you consider a text's purpose, you need to

recognise how the writer has chosen stylistic devices to bring about a

particular series of effects on the reader. One of the most common purposes is

to persuade - and it can be one of the most difficult to determine because

professional writers are experts at making persuasion appear to be

information: quite a different thing (as wartime propaganda has shown).

Audience is also a way to categorise texts.

Referent

A referent is the word to which another word in a sentence or text refers. It is

an important element of textual cohesion. For example, a pronoun must

have a referent noun which is already understood (this noun is called the

pronoun's antecedent) or its meaning will be unclear or ambiguous.

Referents can be exophoric (when the referent is outside of the text),

endophoric (when the referent is within the text), anaphoric (when the

reference precedes the pronoun, e.g. 'John will cook the meal he is a fine

chef.' Here, the pronoun, 'he' is an anaphoric referent) or cataphoric (when

the referent follows the pronoun, e.g. 'I know what he means about it' said

the captain about the steward's behaviour.' - here, the pronouns 'I', 'he'

and 'it' all have cataphoric referents).

Register

When context results in a commonly recognisable style to be produced, the

resulting style is called a register (e.g. an informal register, a medical

register, a scientific register). Context can be an effective way to categorise

texts.

Relative clause

A kind of clause (a group of words built around a subject and verb) that is a

variety of adjectival clause. Relative clauses are used to give extra detail

about the subject or object noun of a main clause in a sentence. e.g. A main

clause might be, 'The butcher sold me some sausages.' and a relative clause

could be, 'who works in Tesco's' . The sentence could then become, 'The

butcher, who works in Tesco's, sold me some sausages.'

A relative clause usually begins with a relative pronoun such as: that,

which, who, whom, although 'that' is often elided as in: 'He knew [that] we

were going early.'.

Repossession

Repossession is a term used in the study of language change. It is used to

describe a word that has fallen out of general use because it is deemed

politically incorrect begins to be reused by the minority group it once referred

to, e.g. the use of the word 'queer' to refer to a homosexual.

Root words

A free morpheme to which can be added a affix (a prefix or suffix) that

acts to change the root word's meaning or function.

Semantics

Semantics is the study of word and phrase meaning (but also see

(semantic)

pragmatics). In the new exam specifications for A-level English Language

(from 2008-9), it has been combined with lexis.

Writers often play with semantics to create interesting stylistic effects or to

create a style suited to a particular context or audience. For example, a

simplified semantic level would be chosen to suit a younger audience, and so

on. When examining a text at the level of its lexis and semantics, it's

important to look out for uses of, for example, irony, simile, semantic fields

(see below) metaphor or hyperbole (called figurative language).

An important area of semantics is in the use of idioms or idiomatic

language.

Semantic/lexical

This term refers to a relationship that exists between some of the words or

field or set

phrases used in a text. This might be because the words have all been chosen

from a similar area of knowledge or interest, e.g. the lexical field/set of

agriculture includes: farm, farming, tractor, meadow, crop, etc. Semantic or

lexical fields can be important in the use of metaphor. A metaphor is a

figurative use of language in which a thing from one semantic field is

described in terms of a different semantic field. For example, in the following

description of a football match, the semantic/lexical field of war is used to

create particular rhetorical effects: 'The home side gunned down the opposing

side with consummate ease'.

Semantic value

The semantic value of a unit of something is the meaning it contains. By

forming words and structuring sentences following the rules of standard

grammar, the semantic value of the sentence and its words and phrases will

be clear and unambiguous.

Sentence

A sentence is a sequence of words constructed in accordance with the

conventions of standard grammar. Such a group will have a sense of

completeness and a clarity of meaning. It will usually be constructed

around a noun phrase acting as the subject of a finite verb, i.e. it will contain

at least one main clause. The rules of grammar concern the order of words in

a sentence, technically called its syntax and the form of the words, called

their morphology.

Sentence 1) below shows standard syntax and morphology (i.e. standard

grammar):

1). 'The cat sat on the mat.'

Sentence 2) shows non-standard morphology:

2). 'The cat sitted the mat on.'

Sentence 3) shows non-standard syntax:

3). 'The cat on the mat sat.'

A group of words that is a sentence is made obvious to the eye (i.e. in writing)

by an opening capital letter and a final full stop, question mark or exclamation

mark. It is made obvious to the ear (i.e. in speech) by the use of pauses. It is

made obvious to the mind because it makes sense alone.

A sentence may loosely be said to be a coherent group of words that

expresses a single complete thought about something (or someone).

A sentence can be one of three main types:

1. A simple sentence is a sentence that contains a single subject and verb,

i.e. an independent clause.

2. A compound sentence is a sentence that contains more than one main

clause. These clauses must be linked by co-ordinating conjunction or a

semicolon.

3. A complex sentence is a sentence that contains a mixture of clause

types. A complex sentence must contain (as all sentences) at least one main

clause but will also contain a second kind of clause acting as a dependent or

subordinate clause. Subordinate clauses often begin with a

subordinating conjunction such as however, although, even though,

because, etc. There is also a special kind of sentence, often used in speech,

called a 'minor sentence'.

A sentence can fulfil one of four functions:

1. It can make a statement. This is called a declarative sentence, e.g. 'I

am overweight.' Declaratives usually follow the word order SV (subject first,

verb second)

2. It can ask a question. This is called an interrogative sentence, e.g. 'Am

I overweight?' and indicated by a question mark. Interrogatives usually follow

the word order VS (verb first, subject second)

3. It can demand an action. This is called an imperative sentence, e.g. 'Sit

down, please.' indicated by a lack of subject (but 'you' is implied).

4. It can make an exclamation. This is called an exclamatory sentence,

e.g. 'What a mess!', indicated by an exclamation mark.

'Minor sentence'

A minor is a sentence without a subject and/or verb. Exclamations are an

example, 'Not on your life!' Poets and writers use them to create the effect of

real conversation.

Sociolect

A sociolect is a variety of language used by a particular social group; a

dialect is a variety of language used in a particular geographical region; and

an idiolect is the variety of language used by a particular individual.

Sign / signifier /

A sign is anything that creates meaning. Words are an important kind of sign

signified

composed of symbols called letters. The brain recognises a word and

unconsciously gives it an agreed meaning, but, in fact, the word is merely a

symbolic code, one that we learn, mostly during childhood, to 'decode' to find

its meaning.

Standard English

This is the agreed standard national dialect of English. Standard English is

generally considered to be the clearest way of expressing meaning and as

such is accepted for use in most textbooks, by teachers, in the news media

and as the basis for English teaching across the world. Non-standard

English includes regional dialects and slang. There are also 'standard forms'

of important international English languages such as 'standard American

English'.

Stem

The 'core' part of a word to which prefixes and suffixes can be added, e.g.

interest which can become uninteresting by adding affixes, the prefix un- and

the suffix -ing.

Structure

The structure of something refers to the form of the complete item - such as a

(structured /

sentence or a text - and the way its individual parts have been put together to

structural)

create a coherent (interrelated) whole. In a phrase, clause or sentence the

individual words are related both by their grammatical structure and their

semantic properties in a text, the relationship and connections between its

structural parts (e.g. its sentences and paragraphs) is considered using

discourse analysis.

Style

Style is the result of the choices a writer (or speaker) makes regarding

(stylistic)

aspects of language, language features and structure with regard to creating a

text or discourse that will suit a particular genre, context, audience and

purpose. Three key aspects of style that are often worthy of comment are a

text's degree of formality or informality, its use of standard or non-standard

grammar and its discourse structure. Some skilled writers also develop

distinctive, individual aspects of style, which may also be called a 'voice' - akin

to a person's spoken idiolect.

Subject and object

The word 'subject' needs care as it has a particular - and very important meaning that is quite distinct to grammar and which is different from its

everyday, non-grammar meaning.

In grammar, the subject (S) is a syntactical position or element within a

clause. The subject can be either a word or a phrase, usually a noun phrase.

In the sentence, 'I gave him a present', 'I' is the grammatical subject and

'gave' is its associated verb in the sentence (in the past tense). In the simple

sentence, 'The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog', the subject is 'The

quick brown fox'. This is a noun phrase that has as its associated finite

verb, 'jumped'. Most English sentences need a subject but sometimes this can

be one of the small words (called pronouns) 'it' or 'there'. This type of subject

can be tricky to recognise as proper subjects.

Some typical word orders of simple declarative sentences are: SV (subjectverb), SVO (subject-verb-object), SVC (subject-verb-complement) or SVA

(subject-verb-adverbial).

Some types of verb transfer their action from their subject onto something

else (the thing receiving the action of the verb is called its object). These are

called transitive verbs. In the above sentence, the verb 'gave' is transitive as

action transfers to the object, the noun 'a present'.

Verbs are called intransitive if they do not transfer action, but, instead, act to

tell what their subject is doing, e.g. 'He is working.', 'It died.' Some verbs can

be either transitive or intransitive according to their usage in the sentence,

e.g. 'He is singing.' (intransitive) and 'He is singing a song.' (transitive).

A few special verbs (stative verbs) have no sense of direct action but,

instead, act to make a statement about their subject's state of being. These

verbs are called copular or linking verbs, e.g. He seems ill, She is clever,

he was a criminal, it appears dark, etc.. The word that follows a stative verb

has no action passing on to it so it cannot be called an object; instead, it is

termed a complement.

Confusingly, Some verbs can take two objects:

'I gave Sally a present.' (i.e. 'I gave a present to Sally')

In this type of sentence, the object is 'a present' (= the thing given; this is

called the DIRECT OBJECT); but there is a second 'object' - the 'receiver' of

the direct object. This is termed the INDIRECT OBJECT. Notice that all

sentences of this type can be re-written as shown using the word 'to'.

Subjunctive

Verb mood used to show a hypothetical situation, e.g. If it were possible, I

would do it.

Suffix

An affix (a morpheme) added to the end of a word to alter its grammatical

function, e.g. the noun luck can become an adjective by adding the suffix

(or 'adjective marker') -y, as in lucky.

Synonym / antonym A word that has a closely similar meaning to another word. English has very

few true synonyms (e.g. sofa / couch / settee), but many near synonyms, e.g.

house - dwelling - home - abode - pad. The existence of synonyms allows

variety of word choice according to style and register. A list of synonyms is

available in a thesaurus.

An antonym is a word with directly 'opposite' meaning, e.g. black/white

good/bad.

Syntax

Syntax is the most important aspect of English grammar. It refers to the

(syntactic /

way words are put together in a group to create meaning as phrases, clauses

syntactical)

or as a sentence. Studying the syntax of a sentence involves investigating the

structure and relationships of its words.

Standard syntax refers to the syntax of a particular dialect of English called

Standard English - this is the syntax you will read in most written texts and

hear from teachers in lessons, newsreaders and in any other more formal

context. Non-standard syntax is a normal part of much spoken English and

is common in regional dialects. Syntax does not have to be standard for

meaning to be clear such as here in the screen play from the film Star Wars

when Yoda speaks:

YODA

Ready, are you? What know you

of ready? For eight hundred years

have I trained Jedi. My own counsel

will I keep on who is to be trained!

A Jedi must have the deepest

commitment, the most serious mind.

(to the invisible

Ben, indicating Luke)

This one a long time have I watched.

All his life has he looked away...

to the future, to the horizon.

Never his mind on where he was.

Hmm? What he was doing. Hmph.

Adventure. Heh! Excitement. Heh!

A Jedi craves not these things.

(turning to Luke)

You are reckless.

Tense

Tense refers to the way the time of an action can be directly indicated in a