UTI-chickens-pitch-2

advertisement

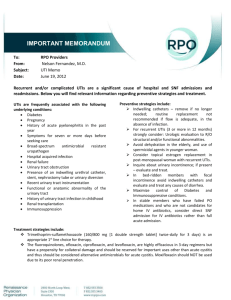

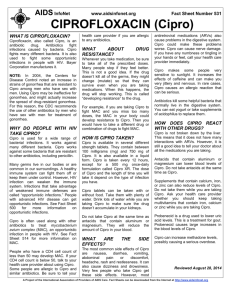

Every year, millions of women contract urinary tract infections. Are farm antibiotics to blame? PITCH MEMO Maryn McKenna Every year, at least 6 million women in the United States contract cystitis: burning, painful inflammations of the bladder and urethra. Most of those urinary tract infections, or UTIs, are caused by the common bacterium E. coli, and an increasing proportion are caused by E. coli that are resistant to common antibiotics. Resistance is such a serious problem that, last year, the major medical society for infectious diseases said it can no longer make a blanket recommendation of which antibiotics to give women with UTIs, for fear they might not work. A small group of researchers in several countries believe they know where that resistance is coming from. In their view, supported by almost a decade of research, the source is one of our most everyday foods: chicken. More than 8 billion meat chickens are raised each year just in the United States, and almost all of them receive antibiotics during their 8-week lifetimes, either to fatten them quickly or to protect them against illness caused by the industrial confinement in which they are raised. When the antibiotics are administered, the E. coli in the guts of those chickens becomes resistant; when the chickens are slaughtered, the E. coli escapes onto their meat. And when consumers buy that meat and eat it, they consume the bacteria too. The E. coli take up residence in that person’s guts and, and at some point down the road, escapes elsewhere in the body and causes a resistant infection. The connection may sound farfetched, but the molecular evidence is solid. In Spain, Denmark, Jamaica, the Netherlands, Canada and the US Midwest, scientists have repeatedly shown close molecular matches between strains of E. coli on retail chicken meat and strains retrieved from people suffering from UTIs. Both the chicken and the human strains share similar patterns of multi-drug resistance – not only to penicillins and tetracyclines, which account for half of the antibiotics used in food animals in the United States, but to other drug classes as well. Provocatively, across that decade human UTIs showed a sharp rise in resistance to fluoroquinolones, which include the human drug Cipro. Fluoroquinolones were banned from use in US poultry in late 2005; shortly after, the rising rate of Cipro resistance in UTIs plateaued. The rate did not reverse, though. That may indicate that resistance, once established, is difficult to defuse — or it may be a demonstration of how global ourt food supply has become, since fluoroquinolones for poultry are still legal in a number of countries. Or is may just indicate that poultry farmers are cheating. A study released just last week found fluoroquinolones in 60 percent of samples of fertilizer made from chicken feathers — drug traces that should not have been present if US farmers were observing the ban. Why hasn’t this connection been covered? UTIs are largely a women’s health issue, and — because they are often linked to sex, which pushes the bacteria toward the bladder — they can be embarrassing as well. But dismissing drug-resistant UTIs as a minor story would be a mistake. There is not only the health-care spending on their treatment: Millions of UTIs translates to millions of doctor’s-office visits, the work hours sacrificed to make those visits, and the price of the prescriptions written during them. There is also the larger cost of not treating them appropriately, if the family physician or gynecologist has not recognized that a resistant bacterium could be to blame. An untreated UTI can climb back up the urinary tract into the kidneys, causing kidney infections, and from there into the bloodstream, causing blood poisoning, septic shock and death.