One-State Article

advertisement

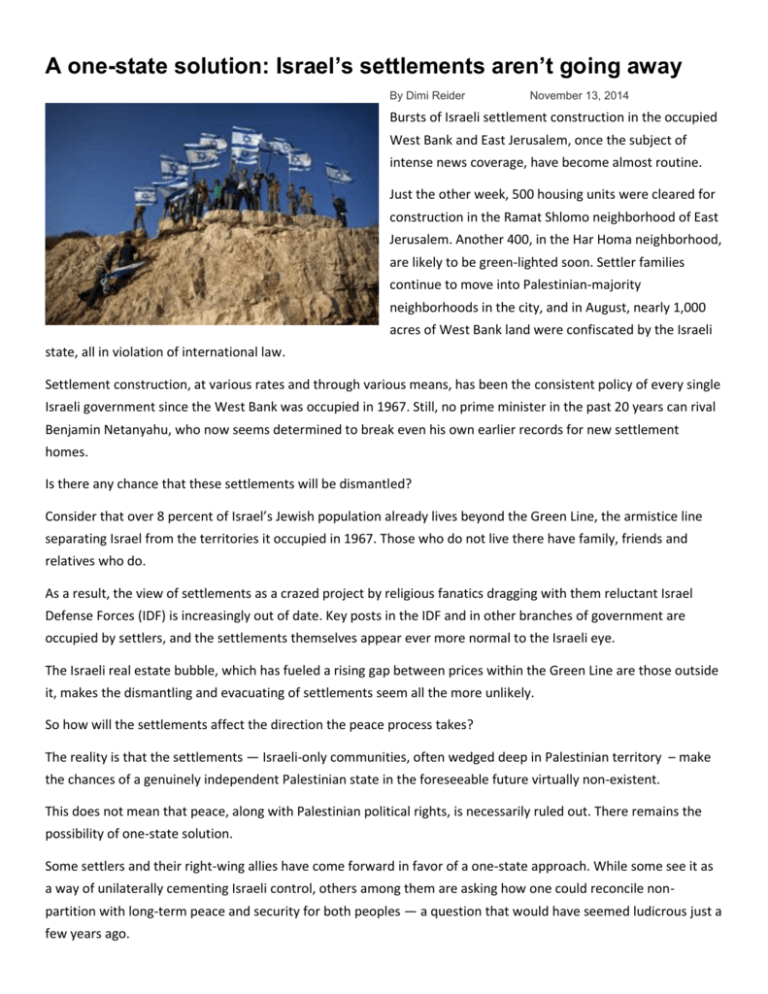

A one-state solution: Israel’s settlements aren’t going away By Dimi Reider November 13, 2014 Bursts of Israeli settlement construction in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, once the subject of intense news coverage, have become almost routine. Just the other week, 500 housing units were cleared for construction in the Ramat Shlomo neighborhood of East Jerusalem. Another 400, in the Har Homa neighborhood, are likely to be green-lighted soon. Settler families continue to move into Palestinian-majority neighborhoods in the city, and in August, nearly 1,000 acres of West Bank land were confiscated by the Israeli state, all in violation of international law. Settlement construction, at various rates and through various means, has been the consistent policy of every single Israeli government since the West Bank was occupied in 1967. Still, no prime minister in the past 20 years can rival Benjamin Netanyahu, who now seems determined to break even his own earlier records for new settlement homes. Is there any chance that these settlements will be dismantled? Consider that over 8 percent of Israel’s Jewish population already lives beyond the Green Line, the armistice line separating Israel from the territories it occupied in 1967. Those who do not live there have family, friends and relatives who do. As a result, the view of settlements as a crazed project by religious fanatics dragging with them reluctant Israel Defense Forces (IDF) is increasingly out of date. Key posts in the IDF and in other branches of government are occupied by settlers, and the settlements themselves appear ever more normal to the Israeli eye. The Israeli real estate bubble, which has fueled a rising gap between prices within the Green Line are those outside it, makes the dismantling and evacuating of settlements seem all the more unlikely. So how will the settlements affect the direction the peace process takes? The reality is that the settlements — Israeli-only communities, often wedged deep in Palestinian territory – make the chances of a genuinely independent Palestinian state in the foreseeable future virtually non-existent. This does not mean that peace, along with Palestinian political rights, is necessarily ruled out. There remains the possibility of one-state solution. Some settlers and their right-wing allies have come forward in favor of a one-state approach. While some see it as a way of unilaterally cementing Israeli control, others among them are asking how one could reconcile nonpartition with long-term peace and security for both peoples — a question that would have seemed ludicrous just a few years ago. The newly elected Israeli president, Reuven Rivlin, is one such politician. The role of the president, though largely ceremonial, is to speak from the very heart of consensus in Israel. That makes it all the more remarkable that Rivlin has already replaced the theme of partition championed by his predecessor, Shimon Peres, with that of a shared partnership and joint future for Israelis and Palestinians — values that would underpin a one-state solution rather than a two-state one. In an interview with the New Yorker, which came out this week, Rivlin defended the settlements. “It can’t be ‘occupied territory’ if the land is your own,” he said. Rivlin advocates a Greater Israel, in which Palestinians would have equal rights. His delicate position as a president at odds with the prime minister prevents him from spelling out a political program. But when I interviewed him in 2010, Rivlin, then speaker of the Knesset, mused about a Belfast-like power-sharing agreement, referring to the complex yet robust peace process in Northern Ireland. He also reflected on the possibility of a rotation-based government, where a Jewish prime minister and his Palestinian deputy would switch roles after set terms. Of all the right-wing leaders, Rivlin is perhaps the most pro-democratic, and contends with strong opposition close to home. Right-wing activists have responded with increasing vitriol to his criticism of racism within Israel, and most right-wing politicians who support a one-state solution don’t share Rivlin’s ideas on power-sharing. Still, the very fact that an Israeli president is giving voice to a vision of one-state partnership will help open the space for a diversity of approaches, both from the right and left. Ultimately, the success of a one-state solution lies with the Palestinians, however. Any proposal that seeks to create one state — even if bi-national — can only be practicable if it comes from the people whose land the settlements are actually built on. The Palestinians are also the only ones who can legitimize any one-state alternative for evicting the settlements, whether desegregation, compensation for the land lost, or both. Since the 1980s, Palestinian politics has been dominated by a vision of a majority nation-state, alongside Israel. This, combined with the well-documented discrimination by Israel against its Palestinian citizens, makes it likely that any offer of citizenship from the Israeli side will be seen — justifiably so — as a means of cementing Israeli domination and control. There have always been dissenting voices, and a growing number of Palestinian activists and intellectuals have already started calling for a one-state solution. But widespread, popular support among Palestinians for such an idea — bold as it is — would be difficult to muster so long as senior Palestine Liberation Organization activists, personally and politically invested in the two-state solution, dominate the Palestinian political arena. But any Israeli initiative can only be offered as a response to a Palestinian one. Otherwise, even the most promising peace plan will be seen as continuation of occupation by other means. PHOTO: Jewish youth hold Israeli flags at the beginning of a rally march in the West Bank settlement of Itamar, near Nablus September 20, 2011. Jewish settlers protested on Tuesday against Palestinian plans to seek United Nations endorsement of statehood in the occupied West Bank, and clashes erupted in one village, underscoring growing tensions in the territory.