Parallel Transformations: Labor and Government in Argentina, 1915

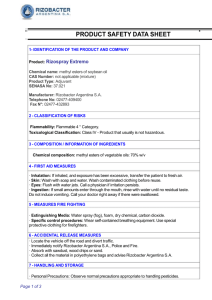

advertisement