Using Databases to Drive Quality Improvement

advertisement

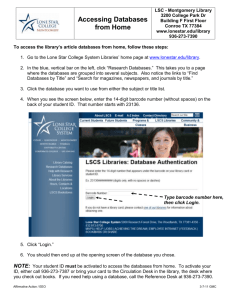

SCA 2014 Colleen G. Koch, MD, MS, MBA Department of Cardiothoracic Anesthesia Quality and Patient Safety Institute Cleveland Clinic Using Databases to Drive Quality Improvement Learning Objectives 1. Become aware of the number of large national databases commonly used for regulatory and quality improvement purposes. 2. Understand the benefits and limitations associated with the use of large administrative databases. 3. Recognize the benefits and limitations of creating large clinical registries for quality improvement research. 4. Learn the utility of both administrative and clinical databases for quality improvement with the use of practical examples from the clinical setting. Understanding Strengths and Weaknesses Healthcare organizations, payers and accrediting agencies are increasingly using administrative data to judge the quality of care delivered. These data sets are relatively inexpensive and originally intended for internal peer review, yet are now being used to drive quality improvement and performance metrics. A number of investigations over the 1 last few decades have highlighted limitations with use of administrative data, in particular for use in risk prediction models and ability to quantify patient outcomes. Early problems with inaccuracies in diagnoses, and inability to differentiate present on admission comorbidity indicators (preexisting comorbidity) from postoperative complications has recently improved, resulting prediction models similar in discrimination to those developed with clinical databases. Clinical databases are expensive, less readily available and require continued resources for proper maintenance, yet often considered the ‘gold’ standard for outcomes assessment. Residual discrepancies between administrative and clinical sources of data may be related to a number of factors such as incomplete coding, lack of standardized definitions, documentation shortcomings and variable coding practices. 1-9 Local and National Clinical Registries and National Administrative Registry Comparisons Administrative data is a valuable source to drive institutional quality improvement initiatives. We found inconsistencies in our institutional quality reported events between our administrative and clinical databases which prompted investigation into determinants of inconsistencies. We examined a national administrative database (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHRQ) and two sources of clinical information, one local (Cardiovascular Information Registry, CVIR) and a national clinical database (National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, NSQIP) on 4 postoperative surgical morbidity outcomes. Considerable discordance was found between the data sources measuring the same 4 postoperative events. Figure 1. A number of factors contributed to discrepancies: data definitions, and collection and 2 management methods. The work highlighted the importance of understanding database shortcomings and specifics of the data to effectively drive quality improvement. 9 Using Databases for Quality Improvement A series of examples demonstrating the use of administrative, national clinical and local clinical registries to drive quality improvement initiatives within a health system will be described. Methods for risk adjustment with the use of administrative data will also be discussed and demonstrated. Figure 1. Kappa coefficients for each postoperative quality indicator and group comparison. AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CVIR, Cardiovascular Information Registry; NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. (From: Koch et al., What are the Real Rates of Postoperative Complications: Elucidating Inconsistencies Between Administrative and Clinical Data Sources. J Am Coll Surg 2012;214:798-805). 3 References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Best WR, Khuri SF, Phelan M, et al. Identifying patient preoperative risk factors and postoperative adverse events in administrative databases: results from the Department of Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. Mar 2002;194(3):257-266. Gross PA, Braun BI, Kritchevsky SB, Simmons BP. Comparison of clinical indicators for performance measurement of health care quality: a cautionary note. Clin Perform Qual Health Care. 2000;8(4):202-211. Hannan EL, Racz MJ, Jollis JG, Peterson ED. Using Medicare claims data to assess provider quality for CABG surgery: does it work well enough? Health Serv Res. Feb 1997;31(6):659-678. Shahian DM, Silverstein T, Lovett AF, Wolf RE, Normand SL. Comparison of clinical and administrative data sources for hospital coronary artery bypass graft surgery report cards. Circulation. Mar 27 2007;115(12):1518-1527. Glance LG, Osler TM, Mukamel DB, Dick AW. Impact of the present-on-admission indicator on hospital quality measurement: experience with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Inpatient Quality Indicators. Med Care. Feb 2008;46(2):112-119. Jollis JG, Ancukiewicz M, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Muhlbaier LH, Mark DB. Discordance of databases designed for claims payment versus clinical information systems. Implications for outcomes research. Ann Intern Med. Oct 15 1993;119(8):844-850. Hannan EL, Kilburn H, Jr., Lindsey ML, Lewis R. Clinical versus administrative data bases for CABG surgery. Does it matter? Med Care. Oct 1992;30(10):892-907. Aylin P, Bottle A, Majeed A. Use of administrative data or clinical databases as predictors of risk of death in hospital: comparison of models. BMJ. May 19 2007;334(7602):1044. Koch CG, Li L, Hixson E, Tang A, Phillips S, Henderson JM. What are the real rates of postoperative complications: elucidating inconsistencies between administrative and clinical data sources. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. May 2012;214(5):798-805. 4