ITB Stretch - Physiotherapy | Rehabilitation | Sports Performance in

advertisement

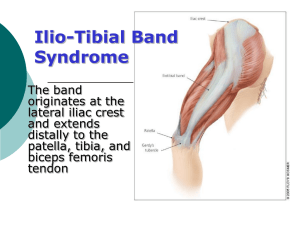

Iliotibial Band Syndrome (ITBS) ITBS is a common overuse injury in runners and cyclists, but can often occur in weight lifters, skiers and footballers (Orchard et al, 1996). ITBS is a result of the friction created between the ITB and the lateral femoral condyle (outside knee). During the cycle of running the friction of the ITB occurs on foot strike where the knee is between 20 and 30⁰ flexion this is the point where the ITB moves from sitting in front of the lateral femoral condyle, to behind the lateral femoral condyle, therefore passing over the bony protrusion (Choi, 2010), irritating the band (see image below). With ITBS downhill runners are more vulnerable to sustaining an irritation, while sprinters are less likely, due to the angles of the knee during the cycle of the stride. As well as friction to the ITB, recent research of ITBS is starting to show that inflammation of the fatty tissue or bursa underneath the ITB can be causing the pain, rather than the band itself (Brukner P & Khan K, 2006). This can be determined on examination by the Physiotherapist, however similar protocols are followed. Anatomy: The ITB is a band of dense fibrous connective tissue that runs distally down the lateral (outside) part of your thigh (Fairclough J et al, 2006). The band runs from the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and iliac crest (top border of the pelvis) along the gluteus maximus, to the Gerdy’s tubercle on the lateral aspect of the tibia, shown in the diagram right. Causes: Increase in running mileage (Noble, 1980) Excessive hill running (Noble, 1980) Poor running technique Poor biomechanics: Increased foot pronation, excessive tibial torsion, excessive varum, weak hip abductors (Noble, 1980 & West R et al, 2009) Reduced range of motion at the ankle Leg length discrepancy Poor footwear (Strauss et al, 2011) Excessive tightness through ITB Signs and symptoms: Pain on the lateral aspect of the knee, which becomes progressively worse on the aggravating activity When symptoms first arise, pain can be worse at the beginning of the activity and start to ease as you get warm, however this will quickly change as symptoms worsen Swelling/ thickening at the area of discomfort (outside of knee) Snapping or popping sensation as the knee is bent Diagnosis: A thorough history is taken, along with a number of tests can be carried out by your Physiotherapist to help diagnose the pathology. An MRI or US scan can be carried out, but will rarely be needed, unless on-going symptoms persist. Self-treatment: Rest from running/cycling Ice Course of anti-inflammatories Foam roller (as demonstrated below) Physiotherapy treatment: Deep friction massage Myofascial release Ischemic pressure Dry needling Foam roller Stretching Strengthening Biomechanical/running assessment Local Corticosteriod injection Surgical release: Last resort post all other intervention Specialist to Sport Dimensions: Close relationship between highly trained Physiotherapists and Rehabilitation staff On site rehabilitation facilities, unique to Sport Dimensions Sister company to The Running School with specialist running coaches Prevention: Use the exercises provided as preventative measures before and after training, especially if you’re a marathon runner, triathlete or even a recreational runner trying to increase fitness. Correctly fitted trainers to help support arches in feet BMA (biomechanical assessment) at the running school. Some self-stretching/ rehabilitation exercises: Foam roller ITB (Iliotibial Band) - Using foam roller or rolled up towel, place under knee as shown in image. Slightly turn foot out Contract quad and hold for 10 secs Repeat 3x10 on each leg Gluteus Medius strengthening - Foam roll ITB’s as demonstrated above for approx. 3x1 minute daily on each leg. ITB stretch Stretch both ITB’s as demonstrated in the image left. You should feel the stretch down the outside of the back leg. Hold for 30-40 secs each time and repeat 3x - As shown in the picture have a slight bend at hips and knees at 90⁰, with feet together. Slowly lift top knee keeping feet together. Make sure hips don’t rotate. You should feel the outside of your hip working. Repeat 3x10 reps Quadriceps stretch - As demonstrated in the picture above stretch both quads, holding for 30-40 secs. Make sure hips are being pushed forward and knees are together, with a slight bend in the weight bearing leg. VMO (Vastus Medialis Oblique) strengthening References: Brukner P & Khan K (2006): Clinical Sports Medicine, 3rd Edition; pp542-545. Choi L (2010): Iliotibial Band Friction Band Syndrome, in DeLee J, drez D Jr, Miller M, eds: DeLee: DeLee and Drez’s Orhtopaedic Sports Medicine, Ed 3. Philidelphia, PA, Saunders Elsevier, pp 627-628. Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H et al (2006): The Functional Anatomy of the Iliotibial Band During Flexion and Extension of the knee: Implications For Understanding Iliotibial Band Syndrome. Journal of Anatomy; 208(3): 309-316. Kwak S D, Ahmad C S, Gardner T R et al (2000). Hamstrings and Iliotibial Band Forces Affect Knee Kinematics and Contact Pattern. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. ; 18: 101-108. Noble C A (1980). Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners. American Journal of Sports Medicine; 8(4): 232-234. Orchard J W, Fricker P A, Abud A T, Mason B R (1996). Biomechanics of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners. American Journal of Sports Medicine; 24: 375-379. Strauss E J et al (2011). Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Evaluation and Management. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 19: 728-736. West R & Irrgang J (2009). Overuse Injuries of the Lower Extremity, 4th Edition; pp181-183.