Dr. Anthony Pizzo - Indiana University

advertisement

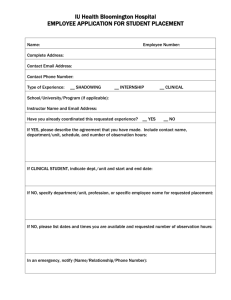

Longtime Bloomington civic leader Anthony Pizzo dies at 93 By By Rod Spaw and Dann Denny 812-331-4350 | rspaw@heraldt.com | Posted: Thursday, January 15, 2015 3:00 am Anthony Pizzo Bloomington city council person Anthony Pizzo listens to public comments about his smoking ban ordinance in this 2003 file photo. Pizzo died Wednesday at 93. STAFF PHOTO BY MONTY HOWELL Longtime Bloomington pathologist and civic leader Dr. Tony Pizzo died Wednesday. He was 93. “Whether it be professionally, personally or politically, Tony Pizzo led a life of service,” said Bloomington Mayor Mark Kruzan, in reflecting upon Pizzo’s multifaceted career as a medical professional, educator and elected official. Upon his selection to the Monroe County Hall of Fame in 2005, The Herald-Times noted that Pizzo had served on nearly 100 state and local commissions and boards — for such entities as the Department of Public Welfare, the Mayor’s Committee on Nuclear Awareness, Harmony School and the Monroe County Chapter of the American Red Cross. He also had a successful political career and won election as a state representative and as Monroe County coroner. As a member of the Bloomington City Council from 1993 to 2003, Pizzo proposed and pushed to reality one of the first smoke-free laws in Indiana, which now applies to Bloomington restaurants, bars and other places of employment and service. City councilman Timothy Mayer, who served on the council with Pizzo, said the Bloomington pathologist was genuine and sincere, someone people could respect. “I learned so many things from Tony by watching and listening to his logic for deciding the best direction to take our city,” Mayer recalled. “Tony would often say, ‘I have been elected to do what is best for our community’ — even though he would go against the popular current at the time.” For more than half a century, Pizzo worked in what is now the IU Health Bloomington Hospital pathology lab, a unit he started and ran by himself in 1951 — the same year he moved to Bloomington with his wife, Patty. At work, he could be seen dressed in his familiar white coat and dark slacks, and a pair of brown eyeglasses perched on the end of his nose gave him an ambassadorial bearing. Pizzo was a sunny-natured man who had an engaging smile and a voice that was soft, low and beautifully modulated. He often sang in the work place, spontaneously busting out tunes such as, “I’m on the Way to Dublin.” He possessed a well-documented wit that often took the form of self-deprecation. He said when he first ran for Monroe County coroner in 1960, it was the same year JFK ran against Nixon. “In Monroe County, I lost by 500 votes, but JFK lost by 7,000,” he once said. “So I beat JFK by 6,500 votes.” Despite Pizzo’s love of laughter, his friends say he was functionally challenged when it came to delivering pre-packaged jokes. “I was always giving him great jokes,” recalled Dr. Mark Braun, a professor of pathology with the IU School of Medicine who was a student of Pizzo’s in the early 1970s and later his partner for nearly 20 years. “But when Tony tried to tell one, the punch line had a way of leaping up into the middle of the joke and biting him on the nose.” For years, Pizzo was the hospital’s elder statesman, serving as a mentor to many younger physicians. Dr. Jean Creek, a retired Bloomington internist, said he was thinking about leaving Bloomington Hospital in the 1950s, until Pizzo talked him out of it. “I would have left if it hadn’t been for him,” he said. “He was very much a mentor to me.” Creek said Pizzo was seen as the CEO of physicians. “Everyone looked up to him,” he said, adding that Pizzo was a “doctors’ doctor.” “He had tremendous respect from all the doctors,” he said. “They would all go to him with questions about medical conditions.” Braun said when Pizzo taught in the medical sciences program at Indiana University, he inspired scores of medical students, including himself, to become pathologists. He said his former students and others in the medical community thought so much of Pizzo that they established an endowment in his name for two scholarships totaling $200,000. The IU Health Bloomington Hospital’s pathology lab is named in his honor. At Bloomington Hospital, Pizzo earned a reputation as a cutting-edge physician who stayed current clinically and technologically. He served as the hospital’s chief of staff from 1989 to 1991, helped start the hospital’s hospice program and was an active member of a board that reviews research projects conducted at the hospital. In 2001, when asked about when he might retire, he crinkled his nose in mock disgust. “I get a great deal of satisfaction coming to work every day, so I have no plans to retire as long as I’m competent,” he said. Five years later, he resigned with honorary status. As a city council member from 1993 to 2003, he was the driving force behind an ordinance to ban smoking in all public places in Bloomington. “I feel more invigorated when I’m busy, especially if I feel I’m contributing something to the community,” he once said. Tim Mayer recalled meeting with Pizzo, former Mayor John Fernandez and a few others in the pathologist’s home to discuss Pizzo’s idea for a smoking ban. “Mayor Fernandez offered that he would give Tony one shot at the proposed legislation without interfering with the council’s business,” Mayer said. “The council meeting debates were rancorous, and Tony was vilified by some. At the end of the debate, the ordinance passed.” Pizzo received dozens of awards for his community service over the years, ranging from the Local Council of Women’s President’s Award in 2003 to the Exchange Club of Northside Bloomington’s Book of Golden Deeds Award in 2005. Humble beginnings As the youngest of three children born to Roman Catholic parents who came to the United States from Sicily in the early 1900s, Pizzo learned early in life about the value of hard work. His father was a railroad worker. His mother was a homemaker who cooked, cleaned and cared for her brood. “They had nothing,” said Fiora Pizzo, his youngest child. “At one point, they lived in a railroad boxcar.” Pizzo’s mother would ask the local butcher for his discarded livers and gizzards — then cook them for dinner. “I hated liver and onions, but Dad loved them and we’d have them for dinner every Thursday,” Fiora said. “But I loved gizzards, and still do. They remind me of him.” While going to school in Logansport and Indianapolis, Pizzo was so far ahead of his classmates that he skipped the third, sixth and eighth grades. He compiled a grade point average at Arsenal Tech High School good enough to secure an academic scholarship to the University of Chicago, where — despite working as a janitor to pay for his room and board — he earned bachelor of science and doctor of medicine degrees. “Most people didn’t know how brilliant he was, because he was so humble,” Fiora said. “He spoke several languages and was always quoting Socrates and Plato.” Touched by an angel As a long-time member of the First Baptist Church/United Church of Christ, Pizzo believed in the existence of heavenly beings. “I honestly feel I have a guardian angel who’s been directing my life all these years,” Pizzo once said. “How else can I explain all the wonderful things that have happened to me?” In 1980, he said it was his personal angel who nudged him to make his first of several medical missionary trips. “I saw a TV news report on the Cambodian refugee camp in Thailand,” he said. “A doctor was walking through an open field, going from body to body. Behind him, men were putting corpses into wheelbarrows. It was very moving.” Later that night, while at church, Pizzo saw a booklet sitting on a table. He opened it to a story in which the International Red Cross was pleading for physicians to volunteer to help provide care in — of all places — Thailand’s refugee camps. “I flew to Thailand and spent six weeks there,” he said. “There were 4,200 refugees in the camp, and I ran a 100-bed hospital, so I kept pretty busy.” Pizzo found the trip so rewarding that he made five more missionary treks over the next two decades, including visits to Zaire, Nicaragua and India. Family first During his senior year in medical school, Pizzo was at a dance when his eyes locked on a co-ed — who, as a freshman undergraduate, was six years his junior. “I was there with a blind date and having a miserable time,” Patty recalled. Patty said when her eyes met Tony’s from across the dance floor, it was love at first sight. He escorted her home that night and they were married a few months later, the day Tony graduated from medical school. Pizzo spoke proudly about his eight children, 16 grandchildren and two greatgrandchildren. One daughter, Amy Margaret, died at the age of 9 in a car accident. One day Fiora went to visit Amy’s grave site and found a bouquet of red roses next to her tombstone. “I asked Dad if he knew anything about it,” she said. “He told me he always put roses there on Amy’s birthday. I had no idea he’d been doing that.” In a 2001 interview, Pizzo said all the kudos he’d received from the community paled compared with “the satisfaction I get from spending time with my children, or getting on the floor and playing with my grandchildren.” His eldest son, screenwriter and film producer Angelo, is probably the most well-known — having written the screenplays for such films as “Hoosiers” and “Rudy.” But all the children are high achievers in one way or another. Son Christopher scaled Mount Everest on a research expedition, and others have chosen professions ranging from law to clinical psychology. Since the birth of his first child, Pizzo harbored a secret dream for his children, a dream that Fiora learned about the night she phoned her father to tell him she’d just finished her senior-year course work at the University of Chicago. “He started crying, so I asked what was wrong,” she said. “He said, ‘All I ever wanted was for all my children to graduate from college.’” Years later, Pizzo grabbed a family photo from an office shelf and hoisted it up like a trophy. “Each of my children has at least two college degrees,” he told a reporter. “That’s not bad.” Patty said her husband attended nearly every one of the children’s Little League games, dance recitals and swim meets and always dropped everything so he could be home for the family dinner at 6 p.m. “After dinner, he’d give the kids baths, read them books and put them to bed,” Patty said. “Then, at about 9, he’d go back to the hospital.” Angelo once said that one of the greatest gifts his father gave him and his siblings was the freedom to pursue their individual interests. “The first-born son of a doctor often feels pressure to follow in his father’s footsteps, but I never felt that from Dad,” he said. “He was always very supportive of whatever interests we had, saying the most important thing was to find something we had a passion for.” When Fiora was 15, Pizzo caught her smoking cigarettes. He marched her to the morgue and showed her the corpse of a person who’d died from lung cancer. “It was the most disgusting thing I’d ever seen, but it made a powerful impression on me,” she said. “He would do whatever it took to protect us.” Fiora said her father loved his children unconditionally. “We were the light of his life,” she said. “All he wanted was for us to be happy and successful. He was the .....” Her voice trailed off, the words catching in her throat. “He was the greatest man I’ve ever known.”