Teacher education resources

advertisement

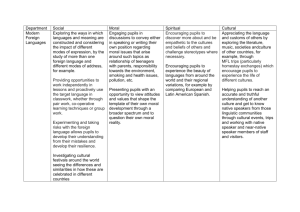

RESOURCES FOR TEACHER EDUCATORS (Janet Orchard and Ruth Heilbronn - PESGB) These resources were circulated following workshops which were a collaboration between the PESGB, the University of Bristol and the Higher Education Academy (HEA), for teacher educators attending with a group of their student teachers. Part A has links to videos that are useful for developing questions for specific contexts in deliberation on ethical issues and values; Part B has some practical suggestions for tasks student teachers on school placement; Part C has follow-up reading related to the issues raised in the workshops, and Part D reports on the workshops. We hope these may be useful to other teacher educators. A. RESOURCES: 1. The Open University Open Learn has published podcasts on ethical issues that are applicable to classroom deliberation: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/whats-on/ethics-bites 2. The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany has documented some experiments with altruism in children and chimps which can serve as stimulus resource on questions relating to cooperation and collaboration and could lead to applied discussions about social issues. The postings which follow the clips are also interesting for discussion points in the classroom. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z-eU5xZW7cU&feature=related 3. Bristol University Physics and Ethics Education Project (PEEP). These materials support bringing ethics into science teaching. Some of the issues can be related to wider subject areas. http://www.peep.ac.uk/content/index.php B. ACTIVITIES FOR STUDENT TEACHERS ON PLACEMENT. From - Heilbronn, R., (2013), ‘Values Education, Deliberation and Discussion’, in Ed. S. Capel. M. Leask, T. Turner.Starting to Teach in the Secondary School,(Unit 4.5. (London, Routledge). 1. AIMS OF THE SCHOOL AND HOW THEY ARE INTERPRETED This task contains several sub-tasks which focus on the aims of the school. Carry out one or more sub-tasks, either alone or in pairs and discuss your findings with other student teachers or your tutors. 1 Collect together the aims of your placement school and, if possible that of another school. Compare and contrast the aims of each school. Does the school in its aims express a responsibility for the moral development of pupils? 1 How are these aims expressed and in what ways do the school statements differ? 2 Many school curricular statements are prefaced with some broad aims, relating to fostering pupils’ self-esteem, valuing their contribution and helping them to develop independently, whilst also enabling them to work with peers. How might these aims of this school curriculum be translated into opportunities for the pupil to achieve them? 3 In what ways does the PSHE programme contribute to the education of your pupils in the area of values? Select a topic, for example: identifying bias and stereotyping and developing strategies to deal with it care of the environment, practices and attitudes towards adult relationships. 4 How might a school assembly contribute to the moral and values education of pupils? Some opportunities for reflection on this might arise by: - attending assembly - keep a record of its purpose, what was said and the way ideas were presented. Interview some pupils afterwards and compare your perception of the session with theirs. Did they understand the underlying point of any ‘message’. If so, did they agree with it? Is the message relevant to their life and their family, and if so, how? - Helping to plan an assembly with a teacher and with the support of other student teachers. Some questions that may be helpful are: - Does the school have a programme for assemblies? How is the content and approach agreed within your school? - How does the content and messages of assemblies relate to the cultural mix of your school? - Does assembly develop a sense of community or is it merely authority enhancing? How is success celebrated and whose success is mostly recognised? 5. What is the school’s programme of in-service education and training (INSET)? Is there any provision relating to moral, ethical and values education? How is such work focused and by whom? (Your school tutor can direct you to the staff responsible for INSET). 2. THE PLACE OF SUBJECT WORK IN PROMOTING MORAL DEVELOPMENT AND VALUES EDUCATION Identify a social, ethical or moral issue that forms part of teaching your subject. Review the issue as a teaching task in preparation for discussing it with other student teachers. Your review could include: - a statement of the subject matter and its place in the curriculum - the ethical focus for pupils - a sample of teaching material - an outline teaching strategy, e.g. a draft lesson plan and consider any problems that you anticipate teaching it - any questions that other student teachers might help you resolve - resources to support the ethical focus. 2 Task 3 CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT 1. Class detention.Consider the following scenario: A class is reading from a set text and from time to time stopping to discuss points. Some children get bored and start to flick pellets at other pupils sitting near the front. The teacher knows it is happening but cannot identify the main culprits. One or two pupils take offence at being hit by pellets and start to complain. The teacher tries unsuccessfully to stop the disruption. The noise level rises and the whole class gets involved. The teacher says that the person who started throwing the pellets will be given a detention and needs to own up. No one owns up and the class is given time to sort it out among themselves if they can. No one owns up and the whole class is kept in after school for 15 minutes. This causes resentment among the pupils and some walk out and refuse to stay. How might the teacher have dealt differently in each case with the following: - the whole incident? - those left in detention? - those who walked out? - Complaints about unfair practice/injustice? What larger themes does this incident raise? (e.g. the justice of collective punishment). C. READINGS 1. ‘Should ‘ought’ be taught?’ by Pat Mahony. Teaching and Teacher Education, Volume 25 (7) Elsevier, Oct 1, 2009 Abstract The argument in this paper is that teachers and other education professionals could benefit from the opportunity to develop ethical understanding, in addition to other aspects of professional knowledge. Having first discussed the nature of ethics, the first main section of the paper establishes the case in favour of including ethical education in the initial or ongoing professional learning of teachers. The case focuses particularly on showing the negative effects of the fashionable claim that ‘values are relative or subjective’ which I argue is a key source of confusion for teachers. In the final part of the paper I discuss some of the kinds of consideration about values and ethics that teachers might find useful. http://www.deepdyve.com/lp/elsevier/should-ought-be-taught-23Ria0dbcc 2. ‘Respecting Profoundly Disabled Learners’ by John Vorhaus, Journal of Philosophy of Education, Volume 40, Issue 3, pages 313–328, August 2006 Abstract The goal of inclusion is more or less credible depending in part on what it is that learners have in common. I discuss one characteristic that all learners are thought to share, although the learners I am concerned with represent an awkward case for the aspiration of inclusivity. Respect is thought of as something owed to all persons, and I defend the view that this includes persons with profound and multiple learning difficulties and disabilities. I 3 also consider the implications of respecting profoundly disabled learners for teaching and learning, and three aspects in particular: treating the profoundly disabled learner as a person; the close relationship between teaching and caring for a vulnerable learner; and individualised learning as an element of a successful teaching and learning environment. www.philosophyofedu 3. ‘Wigs, Disguises and Child’s Play: solidarity in teacher education’ by Ruth Heilbronn, Ethics and Education, Volume 8, Issue 1, 2013, pp. 31-41. Abstract It is generally acknowledged that much contemporary education takes place within a dominant audit culture, in which accountability becomes a powerful driver of educational practices. In this culture, both pupils and teachers risk being configured as a means to an assessment and target-driven end: pupils are schooled within a particular paradigm of education. The article discusses some ethical issues raised by such schooling, particularly the tensions arising for teachers, and by implication, teacher educators who prepare and support teachers for work in situations where vocational aims and beliefs may be in conflict with instrumental aims. The article offers De Certeau's concept of la perruque to suggest an opening to playful engagement for human ends in education, as a way of contending with and managing the tensions generated. I use the concept to recover an idea of solidarity for teacher educators and teachers to enable ethical teaching in difficult times. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17449642.2013.793960 D. REPORT ON WORKSHOPS – Philosophy for Teachers (P4T) Building on earlier work undertaken by the PESGB on the ethical dimensions of teacher education we collaborated with the University of Bristol and the Higher Education Academy HEA on two 24 hour workshops enabling student teachers to think ethically about dilemmas they may face in the classroom. The workshops took place in a Quaker Retreat Centre in rural Oxfordshire. Each blended theoretical perspectives on and systematic ways of thinking about education at an introductory level in response to frequently cited examples of complex and potentially difficult classroom situations. The project was conceived out of a concern that initial teacher education in England is focused too narrowly on the development of beginning teachers’ technical competence and expertise, at the expense of developing their capacity for critical reflection and the exercise of judgement. The aims of the workshops were to: • • • • • create space and time for critical reflection away from the 'busy-ness' of schools through the creation of communities of practice in a residential space conducive to this kind of work explore the value of such a space develop independence and confidence among student teachers on how to manage examples of ethically complex and potentially challenging classroom situations address existential concerns which arise typically among beginning teachers when dealing with challenging behaviour by their pupils, including burnout and sustaining motivation and a sense of ‘moral purpose’ offer teacher educators a form of professional development in the methods of dialogic teaching 4 Small groups of up to 8 participants from Higher Education Institution (HEI), with an accompanying tutor attended, representing a range of educational settings from early years trainees and practitioners to through to post-16 settings, with some undergraduates in Education Studies who had previous school experience in one workshop. This diversity contributed positively to the dynamics and the professional learning of those members of the group. The workshops focussed in particular on moments of ethical discomfort in the classroom/ educational settings and provided opportunities to position these as moral matters rather than purely psychological/ behavioural ones. These were framed as stories. Participants worked together to develop a focus from the stories on ethical concepts, like fairness, respect, trust, equity. These were “stretched”, that is, interrogated slowly and deliberately through debate, and their depth and complexity appreciated. Towards the end of the workshop, tutors and students worked in separate groups to consider ways in which they might follow up the forum and what they had learned from it in their future practice and in a workshop at their home institution. Key findings • There is a need and demand for ethical deliberation amongst teacher-educators and student teachers. Participants valued the space and time for critical reflection away from the 'busy-ness' of their regular programme and reported being able to talk widely about education in a way they had not felt able to do in school. • Participants felt that talking across phase and across institution in particular gave them a good insight into common issues. • A form of ethical deliberation with an experienced facilitator, based on real experiences in the workplace yielded fruitful and enlightening learning experiences. The particular pedagogic model was identified by participants as one they might use themselves in their future classroom practice. • Making space and time for reflective activity of this kind is difficult but possible; participants identified imaginative solutions in the “leaky spaces” to be found in existing provision in which they might develop dialogic teaching within their classroom practice across a range of educational settings. (Janet Orchard, Ruth Heilbronn) 5