Case study Leeds Museums and Galleries Accessioning Archaeology

advertisement

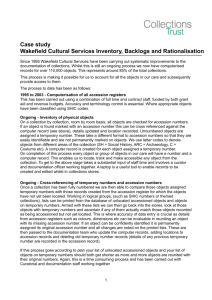

Case study Leeds Museums and Galleries Accessioning Archaeology Traditionally, when accessioning museum collections an accession number is allocated to an object from a chrono-numeric sequence (eg 2003.1, 2003.2, 2003.3 and so on). When accessioning groups of material a part number is used, for example: 2003.1.1 for the first item in the group, 2003.1.2 for the second, 2003.1.3 for the third and so on. When accessioning large archaeological excavation archives using this system the sequence of part numbers could run from say 2003.1.1 up to 2003.1.1001 or any other large number with a long string of digits. Whilst in principle it seems to make sense to give every item from an excavation on a particular site the same accession number (but with different part numbers), in practice it poses some problems. For example it can be very difficult writing an accession number with a long string of digits onto a relatively small item like a sherd or a fragment of bone. It is easy to lose the sequence of part numbers and a mistake early on in the process can result in a lot of work to renumber the collection. There is a different approach, however. Instead of generating a single accession number with changing part numbers for the excavation archive, we could use a group of accession numbers. For example: Small finds from the site could be given the accession number 2003.1 and part numbers 1 to say 100. The group of pottery from context A could be 2003.2 with part numbers, pottery from context B could be 2003.3 and so on. Bulk materials could have a number allocated to them and 2003.4 might be all the unstratified oyster shells from the site. Rather than number all of the shells individually we might write the accession number on the outside of the box, and if there is time, write the accession number on each of the shells. For the purpose of generating computerised documentation a single record could be made noting the number of shells in the box or context or group. This is not as straightforward as using a single accession number for all the objects from the site excavation but it offers greater flexibility. Should another small find turn up from our hypothetical site it would be an easy matter to give it the next part number in the list of part numbers for the accession number reserved for small finds from the site. So far as the computer is concerned it doesn't matter what the number is, provided it is unique. If a mistake was made there is less risk of having to make time-consuming corrections as the collection has already been broken down into smaller groups, each with their own accession number(s). The string of digits for any accession number should also be shorter. Much will depend on the size of the archive and its constituent parts. In some cases it may even be possible to reserve all of the accession numbers from a particular year for a designated excavation, in which case everyone would know that all accession numbers starting with 2003 belonged to an archaeological excavation on site X. This process is unlikely to be undertaken by an archaeological contractor without close supervision by the curator but it does seem to offer advantages over the year and single accession number followed by a long sequence of part numbers approach. Contact Details: Organisation: Leeds Museums and Galleries Address: Abbey House Museum, Abbey Road, Kirkstall, Leeds, LS5 3EH Contact: Bryan Sitch, Curator (Archaeology) Telephone: 0113 230549 1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/uk/ 2