The Rise of Tenement Housing - Watchung Hills Regional High

advertisement

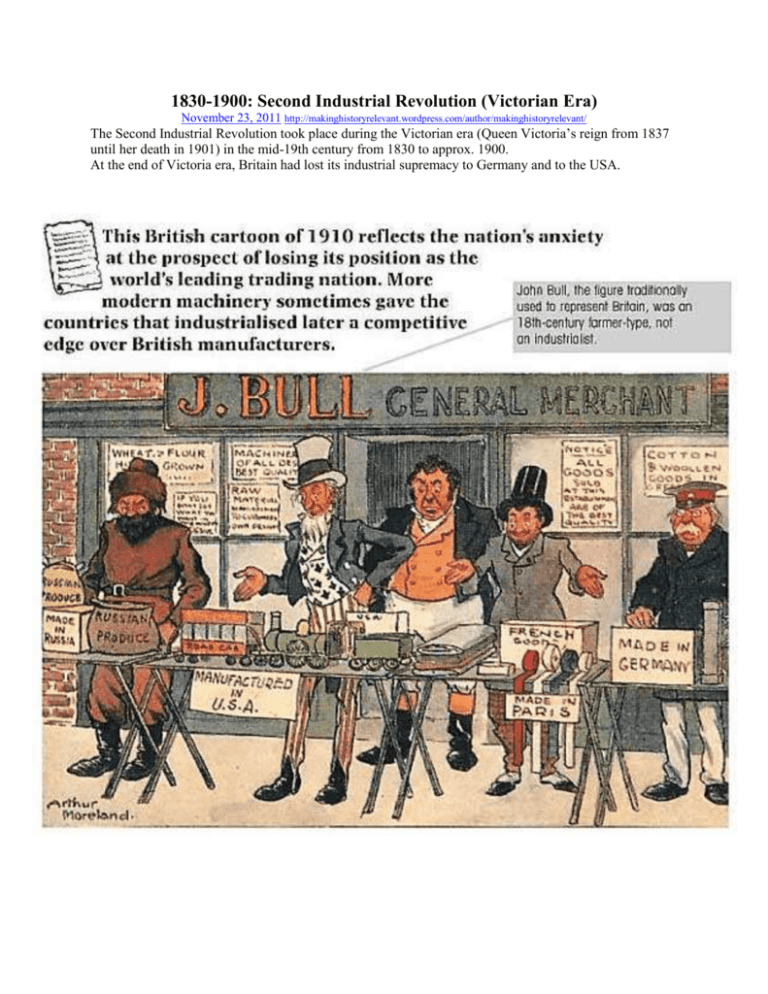

1830-1900: Second Industrial Revolution (Victorian Era) November 23, 2011 http://makinghistoryrelevant.wordpress.com/author/makinghistoryrelevant/ The Second Industrial Revolution took place during the Victorian era (Queen Victoria’s reign from 1837 until her death in 1901) in the mid-19th century from 1830 to approx. 1900. At the end of Victoria era, Britain had lost its industrial supremacy to Germany and to the USA. In the 19th century, more and more people began crowding into America's cities, including thousands of newly arrived immigrants seeking a better life than the one they had left behind. In New York City--where the population doubled every decade from 1800 to 1880--buildings that had once been single-family dwellings were increasingly divided into multiple living spaces to accommodate this growing population. Known as tenements, these narrow, low-rise apartment buildings--many of them concentrated in the city's Lower East Side neighborhood--were all too often cramped, poorly lit and lacked indoor plumbing and proper ventilation. By 1900, some 2.3 million people (a full two-thirds of New York City's population) were living in tenement housing. The Rise of Tenement Housing In the first half of the 19th century, many of the more affluent residents of New York's Lower East Side neighborhood began to move further north, leaving their low-rise masonry row houses behind. At the same time, more and more immigrants began to flow into the city, many of them fleeing famine in Ireland or revolution in Germany. Both of these groups of new arrivals concentrated themselves on the Lower East Side, moving into row houses that had been converted from single-family dwellings into multiple-apartment tenements, or into new tenement housing built specifically for that purpose. A typical tenement building had five to seven stories and occupied nearly all of the lot upon which it was built (usually 25 feet wide and 100 feet long, according to existing city regulations). Many tenements began as single-family dwellings, and many older structures were converted into tenements by adding floors on top or by building more space in rear-yard areas. With less than a foot of space between buildings, little air and light could get in. In many tenements, only the rooms on the street got any light, and the interior rooms had no ventilation (unless air shafts were built directly into the room). Later, speculators began building new tenements, often using cheap materials and construction shortcuts. Even new, this kind of housing was at best uncomfortable and at worst highly unsafe. Calls for Reform New York was not the only city in America where tenement housing emerged as a way to accommodate a growing population during the 1900s. In Chicago, for example, the Great Fire of 1871 led to restrictions on building wood-frame structures in the center of the city and encouraged the construction of lower-income dwellings on the city's outskirts. Unlike in New York, where tenements were highly concentrated in the poorest neighborhoods of the city, in Chicago they tended to cluster around centers of employment, such as stockyards and slaughterhouses. Nowhere, however, did the tenement situation become as dire as it was in New York, particularly on the Lower East Side. A cholera epidemic in 1849 took some 5,000 lives, many of them poor people living in overcrowded housing. During the infamous "draft riots" that tore apart the city in 1863, rioters were not only protesting against the new military conscription policy; they were also reacting to the intolerable conditions in which many of them were living. The Tenement House Act of 1867 legally defined a tenement for the first time and set construction regulations; among these were the requirement of one toilet (or privy) per 20 people. "How the Other Half Lives" The existence of tenement legislation did not guarantee its enforcement, however, and conditions were little improved by 1889, when the Danish-born author and photographer Jacob Riis was researching the series of newspaper articles that would become his seminal book "How the Other Half Lives." Riis had experienced firsthand the hardship of immigrant life in New York City, and as a police reporter for newspapers, including The Evening Sun, he had gotten a unique view into the grimy, crime-infested world of the Lower East Side. Seeking to draw attention to the horrible conditions in which many urban Americans were living, Riis photographed what he saw in the tenements and used these vivid photos to accompany the text of "How the Other Half Lives," published in 1890. The hard facts included in Riis' book--such as the fact that 12 adults slept in a room some 13 feet across, and that the infant death rate in the tenements was as high as 1 in 10-stunned many in America and around the world and led to a renewed call for reform. Two major studies of tenements were completed in the 1890s, and in 1901 city officials passed the Tenement House Law, which effectively outlawed the construction of new tenements on 25-foot lots and mandated improved sanitary conditions, fire escapes and access to light. Under the new law--which in contrast to past legislation would actually be enforced--pre-existing tenement structures were updated, and more than 200,000 new apartments were built over the next 15 years, supervised by city authorities. Family Life and Leisure With standards of living rising, families could pursue activities such as going to the movies. This 1896 French poster advertises the Cinematographe Lumiere, the most successful motion-picture camera and projector of its day. What does the clothing of the people in the poster suggest about their social rank? Florence Nightingale Florence Nightingale became a living legend as the 'Lady with the Lamp'. She led the nurses caring for thousands of soldiers during the Crimean War and helped save the British army from medical disaster. This was just one of Florence's many achievements. She was also a visionary health reformer, a brilliant campaigner, the most influential woman in Victorian Britain and its Empire, second only to Queen Victoria herself. At the start of Pope Benedict XVI visit to Britain in September 2010, he praised Florence's achievements in his Holyroodhouse speech. "We find many examples of this force for good throughout Britain’s long history." "Inspired by faith, women like Florence Nightingale served the poor and the sick and set new standards in healthcare that were subsequently copied everywhere." When she died in 1910, aged 90, she was famous around the world. But who was the real Florence Nightingale? Florence Nightingale was born in Italy on 12th May 1820. Despite opposition from her family she decided to devote her life to nursing and campaigning for better health care and sanitation for all. It was her work during the Crimean War that created the legend of the Lady with the Lamp and it was her experience here that drove her to continue, researching, writing and tirelessly campaigning. After the Crimean War she demanded a Royal Commission into the Military Hospitals and the health of the Army, she began investigating the health and sanitation in the British Army in India, and the local population. Money which had been sent by the general public to thank her for her work in the Crimea was used to establish the first organised, training school for nurses, the Nightingale Training School at St Thomas’ Hospital. Her greatest achievement was to make nursing a respectable profession for women. Florence's writings on hospital planning and organization had a profound effect in England and across the world, publishing over 200 books, reports and pamphlets. Florence died at the age of 90, on 13th August 1910, she had become one of the most famous and influential women of the 19th century. Her writings continue to be a resource for nurses, health managers and planners to this day. Louis Pasteur Pasteur was a French chemist and biologist who proved the germ theory of disease and invented the process of pasteurisation. Louis Pasteur was born on 27 December 1822 in Dole in the Jura region of France. His father was a tanner. In 1847, he earned a doctorate from the École Normale in Paris. After several years research and teaching in Dijon and Strasbourg, in 1854, Pasteur was appointed professor of chemistry at the University of Lille. Part of the remit of the faculty of sciences was to find solutions to the practical problems of local industries, particularly the manufacture of alcoholic drinks. He was able to demonstrate that organisms such as bacteria were responsible for souring wine and beer (he later extended his studies to prove that milk was the same), and that the bacteria could be removed by boiling and then cooling the liquid. This process is now called pasteurization. Pasteur then undertook experiments to find where these bacteria came from, and was able to prove that they were introduced from the environment. This was disputed by scientists who believed they could spontaneously generate. In 1864, the French Academy of Sciences accepted Pasteur's results. By 1865, Pasteur was director of scientific studies at the École Normale, where he had studied. He was asked to help the silk industry in southern France, where there was an epidemic amongst the silkworms. With no experience of the subject, Pasteur identified parasitic infections as the cause and advocated that only disease-free eggs should be selected. The industry was saved. Pasteur's various investigations convinced him of the rightness of the germ theory of disease, which holds that germs attack the body from outside. Many felt that such tiny organisms as germs could not possibly kill larger ones such as humans. Pasteur now extended this theory to explain the causes of many diseases - including anthrax, cholera, TB and smallpox - and their prevention by vaccination. He is best known for his work on the development of vaccines for rabies. In 1888, a special institute was founded in Paris for the treatment of diseases. It became known as the Institut Pasteur. Pasteur was its director until his death on 28 September 1895. He was a national hero and was given a state funeral. The British Cartoon of 1910 1. Explain the political cartoon. How is each country represented? 2. What is the symbolism/message behind the illustration? The Rise of Tenement Housing 3. Many left the lives they had in Europe for a “better life” in America. What conditions did they come to face in the cities? 4. What were these conditions like in contrast to Industrialized cities in Europe such as London? 5. How does Riis express the conditions of the tenements to the American public and what is the reaction? Cinematographe Lumiere 6. What does the clothing of the people in the poster suggest about their social rank? 7. Based on your answer, what does this poster tell you about social classes and the changing living conditions? Florence Nightingale 8. What is Florence Nightingale’s nickname? 9. What advances did she make and why was she such a prominent figure during the Industrial Revolution era? 10. How is she still honored today? 11. How did she gain fame and recognition? Louis Pasteur 12. Who is Louis Pasteur? 13. What was his position at the University of Lille? 14. What did he discover? 15. Explain the process of Pasteurization. 16. How did he save the silk industry in France? 17. What was his “germ theory of disease?” 18. What is he best known for?