Background Information for Teachers

advertisement

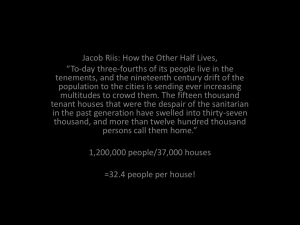

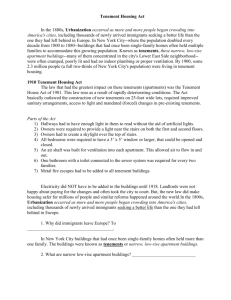

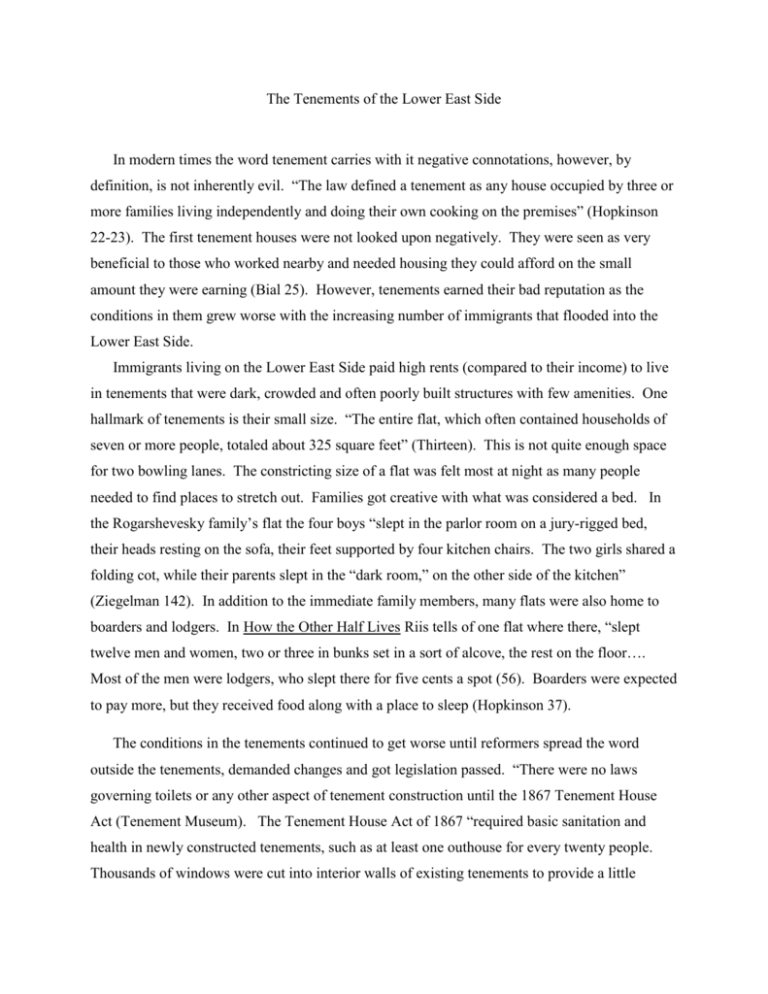

The Tenements of the Lower East Side In modern times the word tenement carries with it negative connotations, however, by definition, is not inherently evil. “The law defined a tenement as any house occupied by three or more families living independently and doing their own cooking on the premises” (Hopkinson 22-23). The first tenement houses were not looked upon negatively. They were seen as very beneficial to those who worked nearby and needed housing they could afford on the small amount they were earning (Bial 25). However, tenements earned their bad reputation as the conditions in them grew worse with the increasing number of immigrants that flooded into the Lower East Side. Immigrants living on the Lower East Side paid high rents (compared to their income) to live in tenements that were dark, crowded and often poorly built structures with few amenities. One hallmark of tenements is their small size. “The entire flat, which often contained households of seven or more people, totaled about 325 square feet” (Thirteen). This is not quite enough space for two bowling lanes. The constricting size of a flat was felt most at night as many people needed to find places to stretch out. Families got creative with what was considered a bed. In the Rogarshevesky family’s flat the four boys “slept in the parlor room on a jury-rigged bed, their heads resting on the sofa, their feet supported by four kitchen chairs. The two girls shared a folding cot, while their parents slept in the “dark room,” on the other side of the kitchen” (Ziegelman 142). In addition to the immediate family members, many flats were also home to boarders and lodgers. In How the Other Half Lives Riis tells of one flat where there, “slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks set in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor…. Most of the men were lodgers, who slept there for five cents a spot (56). Boarders were expected to pay more, but they received food along with a place to sleep (Hopkinson 37). The conditions in the tenements continued to get worse until reformers spread the word outside the tenements, demanded changes and got legislation passed. “There were no laws governing toilets or any other aspect of tenement construction until the 1867 Tenement House Act (Tenement Museum). The Tenement House Act of 1867 “required basic sanitation and health in newly constructed tenements, such as at least one outhouse for every twenty people. Thousands of windows were cut into interior walls of existing tenements to provide a little ventilation from the hallways or other rooms” (Bial 26). More laws were passed in 1879 regulating the amount of space a tenement building could take up on its lot. “Any new tenement could occupy no more than 65 percent of the 25-by-100-foot lot on which it was build- so people would have a little patch of bare soil for a backyard. Living quarters also had to be better ventilated, with windows opening to a narrow air shaft. They came to be called “dumbbell tenements” because of the shape of their revised floor plans” (Bial 28). Although these laws were passed, they weren’t always enforced (Hopkinson 24). Conditions continued to remain the same in the tenements until Jacob Riis published his book “How the Other Half Lives” in 1890 (History.com). Riis’ book shocked people living outside of the Lower East Side and led to a demand for change (History.com). Studies of the conditions in the tenements were completed and led to the passing of the Tenement House Law in 1901 (History.com). This law “effectively outlawed the construction of new tenements on 25-foot lots and mandated improved sanitary conditions, fire escapes and access to light” (History.com).