Complication

advertisement

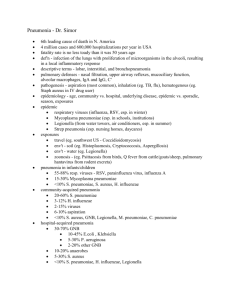

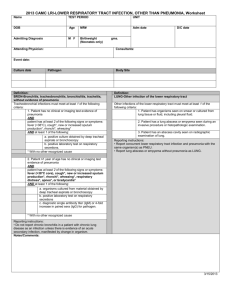

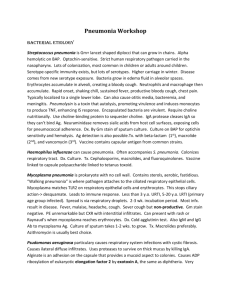

Lec: 4 Dr. Mohammed Alhamdany INFECTION OF RESPIRATORY TRACT Infections of the upper and lower respiratory tract are a major cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients at the extremes of age, and those with preexisting lung disease or immune suppression. Upper respiratory tract infection: Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs), such as coryza (the common cold), acute pharyngitis and acute tracheobronchitis, are the most common of all communicable diseases. It include: 1-Acute coryza (common cold) :Rapid onset sneezing, Sore throat, watery nasal discharge, Cough (Similar features in nasal allergy) Complication: 1-Sinusitis 2-bronchitis 3-pneumonia 4-Hearing impairment, otitis media due to blockage of Eustachian tubes Treatment: not usually required, Paracetamol 0.5–1 g 4–6-hourly, Nasal decongestant. Antibiotics not necessary if uncomplicated. 2-Acute pharyngitis: history of severe sore throat, hoarse voice or loss of voice with pain on speaking. Painful and unproductive cough, stridor in children. Complication: Rare 1- Chronic laryngitis 2-tracheitis 3-bronchitis 4-pneumonia Treatment: Rest voice, Paracetamol 0.5–1 g 4–6-hourly for relief of discomfort and pyrexia. Steam inhalations may help, antibiotics not necessary if uncomplicated. 3- Sinusitis: Fever, Severe unilateral pain over maxillary or other sinus, Purulent nasal discharge. Commonly viral, but bacterial (e.g. Strep. pneumoniae, H. influenzae) likely if persists 7–10 days Complication: CNS or orbital spread of infection Treatment: Steam inhalation and nasal decongestants. Co-amoxiclav if bacterial cause suspected. 4-Acute laryngotracheobronchitis (croup): Sudden paroxysms of cough accompanied by stridor and breathlessness. Contraction of accessory muscles and indrawing of intercostal spaces. Cyanosis and asphyxia in small children Complication: 1-Death from asphyxia 2-Superinfection with bacteria, especially Strep. pneumoniae and Staph. aureus. 3-Viscid secretions may occlude bronchi Treatment: Steam inhalations and humidified air/high concentrations of oxygen, Endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy may be required to relieve laryngeal 1 obstruction and allow clearing of bronchial secretions, Intravenous co-amoxiclav or erythromycin for serious illness, Maintain adequate hydration. 5-Acute epiglottitis Mostly affects young children who present with fever and sore throat, progressing to stridor and dysphagia caused by swelling of epiglottis and surrounding structures it caused by H. influenzae type b. Complication: Death from asphyxia, which may be precipitated by attempts to examine the throat—avoid using a tongue depressor or any instrument unless facilities for endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy are immediately available Treatment: I.v. co-amoxiclav or chloramphenicol therapy essential. Urgent endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy may be necessary. 6-Acute bronchitis and tracheitis: Often follows acute coryza. Initial dry, painful cough with retrosternal discomfort in tracheitis. Chest tightness, wheeze and breathlessness if bronchitis develops. Sputum is initially scanty or mucoid, then becomes mucopurulent, more copious and, in tracheitis, often blood-stained. Acute bronchitis may be associated with a pyrexia of 38–39°C. Spontaneous recovery occurs over a few days Complication: 1-Bronchopneumonia 2-Exacerbation of asthma or COPD which, if severe, may result in type II respiratory failure. Treatment: Specific treatment rarely necessary in previously healthy individuals. Amoxicillin should be given to those developing bronchopneumonia. Cough may be eased by pholcodine .In COPD and asthma, aggressive treatment of exacerbations may be required. 7-Influenza: Range from mild to rapidly fatal. Sudden onset of pyrexia with generalized aching, headache, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and harsh unproductive cough. Most recover within 3–5 days, but may be followed by ‘postviral syndrome’ with debility that persists for weeks. During epidemics, diagnosis is usually obvious. Sporadic cases diagnosed by virus isolation, fluorescent antibody techniques or serological tests for specific antibodies. Complication: 1-Tracheitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis and bronchopneumonia. 2-Secondary bacterial invasion by Strep. pneumoniae, H. influenza and Staph. aureus may occur. 3-Rarely, toxic cardiomyopathy (may cause sudden death), encephalitis, demyelinating encephalopathy and peripheral neuropathy. 4- post-viral syndrome inform of asthenia and depression. 2 Treatment: Bed rest. Paracetamol , Pholcodine for cough. Specific treatment for pneumonia may be necessary. Antiviral agents (e.g. zanamivir) reduce the rate of viral replication and may be effective when used as an adjunct to vaccination. Pneumonia Pneumonia is as an acute respiratory illness associated with recently developed radiological pulmonary shadowing, which may be segmental, lobar or multilobar. Classification: pneumonias are usually classified as 1- community-acquired 2hospital-acquired 3- Pneumonia occurring in immunocompromised hosts. Pathophysiology: ‘Lobar pneumonia’ is a radiological and pathological term referring to homogeneous consolidation of one or more lung lobes, often with associated pleural inflammation. ‘Bronchopneumonia’ refers to more patchy alveolar consolidation associated with bronchial and bronchiolar inflammation, often affecting both lower lobes. The inflammatory response in lobar pneumonia evolves through stages of congestion, red then grey hepatisation, and finally resolution. Community-acquired pneumonia It accounting for around 5–12% of all lower respiratory tract infections. It affects all age groups but is particularly common at the extremes of age; worldwide, CAP continues to kill more children than any other illness, and its propensity to ease the passing of the frail and elderly led to pneumonia being known as the ‘old man’s friend’. Most cases are spread by droplet infection and, whilst CAP may occur in previously healthy individuals, several factors may impair the effectiveness of local defences and predispose to CAP and as following; 1-Cigarette smoking 2- Pre-existing lung disease 3-Indoor air pollution 4-Upper respiratory tract infections 5- Recent influenza infection 6- HIV 7- Alcohol 8-Corticosteroid therapy 9- Old age Etiology: Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the most common infecting agent. The likelihood that other organisms may be involved depends on the age of the patient and the clinical context. Viral infections are important causes of CAP in children, and their contribution to adult CAP is increasingly recognised. A ‘best guess’ as to the likely organism may be made from the context in which pneumonia develops, but not from the clinical and radiological picture, which does 3 not differ sufficiently from one organism to another; the term ‘atypical pneumonia’ has therefore been dropped. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is more common in young people and rare in the elderly, whereas Haemophilus influenzae is more common in the elderly, particularly when underlying lung disease is present. Legionella pneumophila occurs in local outbreaks centred on contaminated cooling towers in hotels, hospitals and other industrial buildings. Staphylococcus aureus is more common following an episode of influenza. respiratory syndrome (SARS), caused by a form of coronavirus arising in the China, but which spread rapidly through Hong Kong and Vietnam, and then throughout the world. Clinical features: A-history: 1-Pneumonia, particularly lobar pneumonia, usually presents as an acute illness. Systemic features such as fever, rigors, shivering and malaise predominate and delirium may be present. The appetite is invariably lost and headache frequently reported. 2-Pulmonary symptoms include cough, which at first is characteristically short, painful and dry, but later accompanied by the expectoration of mucopurulent sputum. Rust-coloured sputum may be seen in patients with Strep. pneumoniae, and the occasional individual may report haemoptysis. 3- Pleuritic chest pain may be a presenting feature and, on occasion, may be referred to the shoulder or anterior abdominal wall. Upper abdominal tenderness is sometimes apparent in patients with lower lobe pneumonia or if there is associated hepatitis. B-On examination: 1- the respiratory and pulse rate may be raised and the blood pressure low, while an assessment of the mental state may reveal a delirium. These are important indicators of the severity of the illness 2- Not all patients are pyrexial but this is a helpful diagnostic clue if present. 3-Oxygen saturation on air may be low, and the patient cyanosed and distressed. 4-Chest signs vary, depending on the phase of the inflammatory response. When consolidated, the lung is typically dull to percussion and, as conduction of sound is enhanced, auscultation reveals bronchial breathing and whispering pectoriloquy; crackles are heard throughout. 5-On occasion, inferences as to the likely organism may be drawn from clinical examination. For example, the presence of herpes labialis may point to streptococcal infection, The presence of poor dental hygiene should prompt consideration of Klebsiella. 4 Examples of CAP according to types of micro-organism: 1-Streptococcus pneumoniae Most common cause. Affects all age groups, particularly young to middle-aged. Characteristically rapid onset, high fever and pleuritic chest pain; may be accompanied by herpes labialis and ‘rusty’ sputum. Bacteraemia more common in women and those with diabetes or COPD. 2-Mycoplasma pneumoniae Affect children and young adults. Epidemics occur every 3–4 years, usually in autumn. Rare complications include haemolytic anaemia, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, erythema nodosum, myocarditis, pericarditis, meningoencephalitis, Guillain–Barré syndrome. 3-Legionella pneumophila Occur Middle to old age. Local epidemics around contaminated source, e.g. cooling systems in hotels, hospitals. Person-to-person spread unusual. Some features more common, e.g. headache, confusion, malaise, myalgia, high fever and vomiting and diarrhoea. Laboratory abnormalities include hyponatraemia, elevated liver enzymes, hypoalbuminaemia and elevated creatine kinase. Smoking, corticosteroids, diabetes, chronic kidney disease increase risk. 4-Haemophilus influenzae More common in old age and those with underlying lung disease (COPD, bronchiectasis) 5-Staphylococcus aureus Associated with debilitating illness and often preceded by influenza. Radiographic features include multilobar shadowing, cavitation, and abscesses. Dissemination to other organs may cause osteomyelitis, endocarditis or brain abscesses. Mortality up to 30%. 6-Klebsiella pneumonia (Freidländer’s bacillus) More common in men, alcoholics, diabetics, elderly, hospitalised patients, and those with poor dental hygiene. Predilection for upper lobes and particularly liable to suppurate and form abscesses. May progress to pulmonary gangrene Investigation: A-Blood 1-Full blood count • Very high (> 20 × 109/L) or low (< 4 × 109/L) white cell count: marker of severity • Neutrophil leucocytosis > 15 × 109/L: suggests bacterial aetiology • Haemolytic anaemia: occasional complication of Mycoplasma 2-Urea and electrolytes • Urea > 7 mmol/L (~20 mg/dL): marker of severity 5 • Hyponatraemia: marker of severity 3-Liver function tests • Abnormal if basal pneumonia inflames liver • Hypoalbuminaemia: marker of severity 4-Erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein • Non-specifically elevated 5-Blood culture • Bacteraemia: marker of severity 6-Serology • Acute and convalescent titres for Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Legionella and viral infections Cold agglutinins • Positive in 50% of patients with Mycoplasma 7-Arterial blood gases • Measure when SaO2 < 93% or when severe clinical features to assess ventilatory failure or acidosis B-Sputum 1-Sputum samples • Gram stain , culture and antimicrobial sensitivity testing Oropharynx swab • PCR for Mycoplasma pneumoniae and other atypical pathogens C-Urine • Pneumococcal and/or Legionella antigen D-Chest X-ray 1-Lobar pneumonia • Patchy opacification evolves into homogeneous consolidation of affected lobe • Air bronchogram (air-filled bronchi appear lucent against consolidated lung tissue) may be present 2-Bronchopneumonia • Typically patchy and segmental shadowing 3-Complications • Para-pneumonic effusion, intrapulmonary abscess or empyema 4-Staph. aureus • Suggested by multilobar shadowing, cavitation, and abscesses E-Pleural fluid • Always aspirate and culture when present in more than trivial amounts, preferably with ultrasound guidance 6 Assessment of severity of CAP According to Hospital CURB-65 Differential diagnosis of CAP 1- Pulmonary infarction 2- Pulmonary/pleural TB 3- Pulmonary edema (can be unilateral) 4- Pulmonary eosinophilia 5- Malignancy: bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma 7