The Relationship Between FLUTD and Urolithiasis in Cats Angela

advertisement

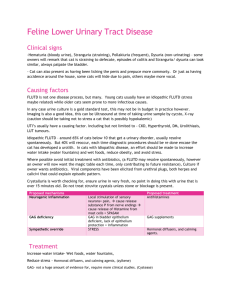

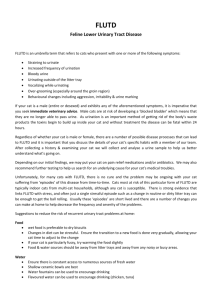

Running Head: FLUTD & UROLITHIASIS The Relationship Between FLUTD and Urolithiasis in Cats Angela Culp Michelle Hervey James Hulse Tarleton State University Companion Animal Nutrition VETE 4323 – 011 10-28-15 1 FLUTD AND UROLITHIASIS 2 Lower urinary tract disease in cats has had a variety of names over the years. These names include feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD), feline urologic syndrome (FUS), and the most commonly used term today is feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) (Merrill, 2012). FLUTD is a collaboration of many different lower urinary tract disorders in cats for anything that causes problems in the urinary bladder and urethra. Though there are many causes of FLUTD, the majority appears to be feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC), urolithiasis, and urethral plugs (Forrester, Kruger, & Allen, 2010). This paper will discuss FIC, including what veterinarians believe to be the contributing factor of the disorder, the common types of uroliths, and what causes them to form in the urinary system. FLUTD and urolithiasis in cats has shown to be controlled by the alteration of the cat’s diet. The different types of diets offered will also be discussed. “Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease (FLUTD) is a term used to describe a condition of unknown etiology in cats characterized by dysuria, hematuria, pollakiuria, urinating in uncommon places and occasional urethral obstruction” (Komurek, 2014). The differential diagnosis of FLUTD is: feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC), urethral plug (obstructive FIC), bacterial cystitis, stricture, neoplasia, and urolithiasis (struvite, calcium oxalate, urate, and cysteine) (Thompson, 2014). Of those uroliths listed, struvite and calcium oxalate are the two most common to affect felines (Komurek, 2014). FLUTD syndrome is a multifactorial disease, meaning that not all causes of this disease are known. In order to control this disease, there should be a change over the urine mineral concentration or pH. This, however, is not a fix all to this disease. In some cases, you cannot determine the cause, so the diagnosis would be idiopathic FLUTD. The potential causes of this diagnosis include viral infection, stress, and neurogenic inflammation (Komurek, 2014). The following are clinical signs of FLUTD: straining to urinate (may appear constipated to the FLUTD AND UROLITHIASIS 3 owner), vomiting, dehydration, sudden collapse, vocalizing, painful abdomen, and may be urinating in strange places, if able to pass any urine at all (Summers, 2014). Any urethral blockage that occurs can be fatal and needs to be addressed immediately. This treatment could include: surgery (removal of stones), urinary catheter with hospitalization for fluids, antibiotics only if there is a urinary tract infection, amitriptyline to relieve clinical signs and ease discomfort, Prazosin to relieve incontinence, and a change in diet (Summers, 2014). A change in diet can be a solution and/or prevention. Prevention of FLUTD is to provide a high moisture or canned food and high water intake to help in the control and prevent the recurrence of the disease. A diet containing 20mg of magnesium per 100 kcals helps to maintain a urine pH of 6.4. One such diet is Hill’s Prescription Diet® c/d® feline maintenance. The basis of changing the diet to a more acidifying state is to help break down the crystals and keep them from clumping in the urethra (Komurek, 2014). “Urolithiasis is now considered to be one manifestation of a collection of lower urinary tract disorders collectively referred to as FLUTD. Urolithiasis is characterized by the presence of urethral plugs, urinary crystals (crystalluria), uroliths, or calculi within the bladder and urethra, or both” (Case, Daristotle, Hayek, & Raasch, 2011). According to Forrester et al. (2010) clinical signs for urolithiasis include pollakiuria, oliguria, stranguria, dysuria, hematuria and inappropriate urination. The most commonly seen uroliths found in cats are struvite and calcium oxalate uroliths. These uroliths form in specific types of urine pH and are related to the cat’s diet. Uroliths, also known as calculi or stones, in the urinary tract result from super-saturation of urine with particular stone-forming substances or crystalline components (Merrill, 2012). Urolithiasis is typically not seen in cats that are younger than 1 year of age. Cats will typically be diagnosed for the first time between the ages of 2 to 6 years old. At this age, it is most FLUTD AND UROLITHIASIS 4 common that these cats are presenting with struvite urolithiasis. In cats that are over the age of 7 years old, they most commonly present with calcium oxalate urolithiasis. The urinary bladder is the most common place of formation. The reason being that the urinary bladder holds the urine for a longer period of time, which gives the stone-forming substances or crystalline substances an increased amount of time to be in contact. The more time these substances have to be in contact with each other, the higher the risk of the development of uroliths and crystalluria. The other major factor in crystalluria or urolith development is the cat’s diet. The changes in urine pH can be altered by the cat’s diet causing urolithiasis. Urolithiasis can be life threatening to the cat because if the clinical signs have gone unnoticed, the cat’s urethra can become obstructed with uroliths causing them to become anuric, leading to rupture of the bladder. It is important to remember that the presence of crystalluria does not mean that the cat will develop uroliths. When cats are presenting to the clinic with signs of urolithiasis, it is important to perform a urinalysis and urine culture with sedimentation. The urinalysis will determine the urine pH, hematuria, proteinuria, and urine specific gravity. The sedimentation will indicate the type of crystalluria and or urolith type. Struvite Uroliths The major urolith in cats is the struvite uroliths. The struvite urolith is identified by its mineral composition of magnesium ammonium phosphate (Grauer, 2015). There are two versions of the struvite urolith: sterile and non-sterile. Bacteria in the urine produce urease, which increases the ammonium concentration and pH to form non-sterile struvites. On the other hand, struvites formed in sterile urine is caused by dietary and metabolic factors that result in an alkaline urine (Grauer, 2015). Sterile struvites are more likely to form in urine with a pH of 6.56.9 (Lekcharoensuk et al., 2001). Female cats between the age of two and seven years of age FLUTD AND UROLITHIASIS 5 have an increased risk of struvite uroliths. Methods of detection include radiography and ultrasonography. Medical treatment involves antibiotics to treat the non-sterile urolith causing bacteria. A struvite dissolution diet is also introduced for a short period of time. Uroliths and crystalluria that will not dissolve will need to be surgically removed (Summers, 2014). Lithotripsy, hydropulsion of the urethra, or cystocentesis can also be utilized to aid in dissolution of the uroliths. Calcium Oxalate Uroliths Calcium oxalate uroliths are the next major category to cause urolithiasis. This type is caused by an oversaturation of calcium and oxalate in the urine. This urolith is mostly caused by the diet having too much oxalate or too little calcium. Acidifying diets that cause a pH of 6 – 6.2 has an increased risk of causing calcium oxalate uroliths. Other risk factors include male cats that are between eight and twelve years of age. Diagnosis and treatment of calcium oxalate uroliths is the same as struvite uroliths. Though there are no dissolution diets for this type of urolith, there are prevention diets. Increased Water Consumption Increasing the cat’s water intake can also dissolve crystalluria and uroliths. Increasing the water intake will dilute the urine and cause the cat to urinate more frequently. The more frequent the urination, the shorter amount of time the urine is in the bladder. This will decrease the risk of crystalluria and/or urolith formation within the urinary bladder and urethra. Prescription Diets “Nutritional management plays a key role in the treatment of patients with FIC, struvite disease (uroliths and urethral plugs), and calcium oxalate uroliths” (Forrester et al., 2010). According to Komurek (2014), the type of stone that is produced will dictate the diet used to FLUTD AND UROLITHIASIS 6 modify urine pH. There are many types and brands of cat food that can be used to treat urolithiasis. Hill’s® has several prescription diets that are indicated for FLUTD and urolithiasis and some with concurrent problems such as diabetes mellitus and obesity prone. They also have one diet that is indicated for struvite dissolution. It is Prescription Diet® s/d® Feline Dissolution. It has reduced magnesium, added antioxidants, and aims for a pH of 5.9 – 6.1. Royal Canin also makes cat foods that are indicated for FLUTD and urolithiasis. Royal Canin Veterinary Diet® Urinary SO® is indicated to dissolve struvite uroliths and to prevent struvite urolithiasis, calcium oxalate urolithiasis, and calcium phosphate urolithiasis. Purina makes UR Urinary St/Ox® which is indicated for struvite-associated FLUTD, dissolution of sterile struvite uroliths, reduced risk of both struvite and calcium oxalate uroliths, and for FIC. These diets also promote dilute urine. Feline lower urinary tract disease is an all-inclusive clinical term that refers to anything that causes irritation to the bladder or urethra (Komurek, 2014). Urolithiasis creates inflammation of the bladder or urethra that is caused by urinary stones called uroliths. These uroliths are most commonly composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvites) or calcium oxalate. Prevention of stones and other crystals includes increasing water content and making changes to the diet. There are several diets that can dissolve uroliths and several that can prevent uroliths by increasing or decreasing the acidification of the urine pH. 7 FLUTD AND UROLITHIASIS References Case, L.P., Daristotle, L., Hayek, M.G., & Raasch, M.F. (2011). Canine and feline nutrition (3rd ed.). Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier. Forrester, S.D., Adams, L.G., & Allen, T.A. (2010). Chronic kidney disease. In M.S. Hand, C.D. Thatcher, R.L. Remillard, P. Roudebush, & B.J. Novotny (5th ed.), Small animal clinical nutrition (pgs. 281 - 294). Topeka, KS: Mark Morris Institute. Grauer, G.F. (2015). Feline struvite & calcium oxalate urolithiasis. Today’s veterinary practice, 5(5), 14 – 20. Hill’s key to clinical nutrition. (2015). Komurek, K. (2014). Small animal medical nursing. In J.M. Bassert & J.A. Thomas (8th ed.), McCurnin’s clinical textbook for veterinary technicians (pgs. 672 – 719). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. Lekcharoensuk, C., Osborne, C.A., Lulich, J.P., Pusoonthornthum, R., Kirk, C.A., Ulrich, L.K., Swanson, L.L. (2001). Association between dietary factors and calcium oxalate and magnesium ammonium phosphate urolithiasis in cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 219(9), 1228 – 1237. Merrill, L. (2012). Small Animal internal Medicine for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell. Purina product guide for veterinary clinics. (2013). Royal Canin product book. (2012). FLUTD AND UROLITHIASIS Summers, A. (2014). Common diseases of companion animals (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby. Thompson, M.S. (2013). Small animal medical differential diagnosis (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders. 8