Case biz - openCaselist 2015-16

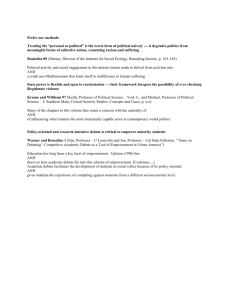

advertisement