JEAN-BAPTISTE COLBERT, The Advantages of Colonial Trade

advertisement

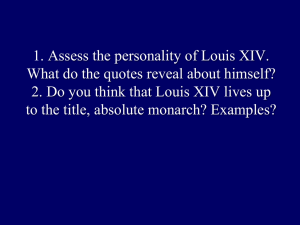

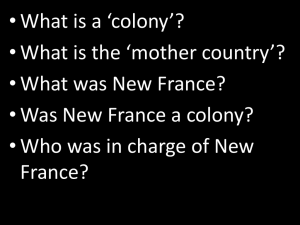

JEAN-BAPTISTE COLBERT, The Advantages of Colonial Trade (1664) Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683) came from a family of wealthy French merchants. He first achieved political prominence during the early years of Louis XIV's reign, in the service of Cardinal Jules Mazarin, Louis's political mentor and advisor. Following Mazarin's death in 1661 until his own in 1683, Colbert served Louis XIV as both minister of finance and minister of marine and colonies. He was a staunch proponent of mercantilism, in which the government regulates economic activities in order to increase the wealth of the state. To this end, he commissioned a pamphlet from which the following excerpt is drawn, in which he tried to encourage French merchants to invest in the state's East India Company. Now of all commerces whatsoever throughout the whole world, that of the East Indies'- is one of the most rich and considerable. From thence it is (the sun being kinder to them, than to us) that we have our merchandise of greatest value and that which contributes the most not only to the pleasure of life but also to glory, and magnificence. From thence it is that we fetch our gold and precious stones and a thousand other commodities (both of a general esteem and a certain return) to which we are so accustomed that it is impossible for us to be without them, as silk, cinnamon, pepper, ginger, nutmegs, cotton cloth, ouate [cotton wadding], porcelain, woods for dyeing, ivory, frankincense, bezoar [poison antidote], etc. So that having an absolute necessity upon us, to make use of all these things, why we should not rather furnish ourselves, than take them from others, and apply that profit hereafter to our own countrymen, which we have hitherto allowed to strangers, I cannot understand. Why should the Portuguese, the Hollanders [Dutch], the English, the Danes, trade daily to the East Indies possessing there, their magazines, and their forts, and the French neither the one nor the other? ... To what end is it in fine that we pride ourselves to be subjects of the prime monarch of the universe, if being so, we dare not so much as show our heads in those places where our neighbors have established themselves with power? .. . What has it been, but this very navigation and traffic that has enabled the Hollanders to bear up against the power of Spain,3 with forces so unequal, nay, and to become terrible to them and to bring them down at last to an advantageous peace? Since that time it is that this people, who had not only the Spaniards abroad, but the very sea and earth at home to struggle with, have in spite of all opposition made themselves so considerable, that they begin now to dispute power and plenty with the greatest part of their neighbors. This observation is no more than truth, their East India Company being known to be the principal support of their state and the most sensible cause of their greatness. READING AND DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Why do you think Colbert found it so objectionable that the French depended on middlemen ("the Portuguese, the Hollanders, the English, the Danes") to provide France with the riches of India, rather than obtaining them themselves? 2. Why do you think Colbert stressed "the pleasure of life but also to glory, and magnificence" that Indian goods provided to France? What does his emphasis tell us about the culture of French absolutism? 3. Based on the language of his treatise, whom does Colbert seem to blame for the absence of direct French trade with the West Indies? MOLIERE, from Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1671) Moliere (1622-1673) was an outstanding playwright at the court of Louis XIV, and among the very greatest in French history. Unlike his contemporary Jean Racine, who wrote tragedies, Moliere excelled at satirical comedies such as Tartuffe, which played on the prejudices of his employer and mocked the foibles of humankind. In this excerpt from Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (The Middleclass Gentleman), Moliere ridicules the aspirations Monsieur Jourdain entertains for his daughter, at the same time depicting Madame Jourdain as a mouthpiece for a social order in which everyone "knows their place." M. JOURDAIN: Shut up, saucebox. You're always sticking your oar in the conversation. I have enough property for my daughter; all I need is honor; and I want to make her a marquise.(marry her to a noble) MME. JOURDAIN: Marquise? M. JOURDAIN: Yes, marquise. MME. JOURDAIN: Alas, God forbid! M. JOURDAIN: It's something I've, made up my mind to. MME. JOURDAIN: As for me, it's something I'll never consent to. Alliances with people above our own rank are always likely to have very unpleasant results. I don't want to have my son-in-law able to reproach my daughter for her parents, and I don't want her children to be ashamed to call me their grandma. If she should happen to come and visit me in her grand lady's carriage, and if by mistake she should fail to salute some one of the neighbors, you can imagine how they'd talk. "Take a look at that fine Madame la Marquise showing off," they'd say. "She's the daughter of Monsieur Jourdain, and when she was little, she was only too glad to play at being a fine lady. She wasn't always so high and mighty as she is now, and both her grandfathers sold dry goods besides the Porte Saint Innocent. They both piled up money for their children, and now perhaps they're paying dear for it in the next world; you don't get so rich by being honest." Well, I don't want that kind of talk to go on; and in short, I want a man who will feel under obligation to my daughter, and I want to be able to say to him: "Sit down there, my boy, and eat dinner with us." M. JOURDAIN: Those views reveal a mean and petty mind, that wants to remain forever in its base condition. Don't answer back to me again. My daughter will be a marquise in spite of everyone; and if you get me angry, I'll make her a duchess. READING AND DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Monsieur Jourdain states that he has property enough for his daughter's dowry. Why is he so eager to secure "honor" for her as well? 2. Why does Madame Jourdain object to her daughter marrying "above her own rank"? 3. What does Moliere's satire suggest about the relative importance of wealth and social origins in determining one's status in Louis XIV's France? Does Moliere seem to prefer Monsieur or Madame Jourdain's opinion? Duke of Saint-Simon, Memoire Louis XIV of France was the most powerful ruler of his time. He had inherited the throne as a child in 1643. He took personal command by 1661, ruling France until his death in 1715. Contemporary rulers viewed him as a model ruler. One of the ways in which he reinforced his position was by conducting a magnificent court life at his palace of Versailles. There, nobles hoping for favors or appointments competed for his attention and increasingly became dependent upon royal whim. One of those nobles, the Duke of Saint-Simon (1675-1755), felt slighted and grew to resent the king. SaintSimon chronicled life at Versailles in his Memoires. In the following excerpt, he shows how Louis XIV used this court life to his own ends. CONSIDER: How the king's activities undermined the position of the nobility; the options available to a noble who wanted to maintain or increase his own power; how the king's activities compare with the great elector's recommendations to his son. Frequent fetes, private walks at Versailles, and excursions were means which the King seized upon in order to single out or to mortify [individuals] by naming the persons who should be there each time, and in order to keep each person assiduous and attentive to pleasing him. He sensed that he lacked by far enough favors to distribute in order to create a continuous effect. Therefore he substituted imaginary favors for real ones, through jealousy—little preferences which were shown daily, and one might say at each moment—[and] through his artfulness. The hopes to which these little preferences and these honors gave birth, and the deference which resulted from them—no one was more ingenious than he in unceasingly inventing these sorts of things. Marly, eventually, was of great use to him in this respect; and Trianon, where everyone, as a matter of fact, could go pay court to him, but where ladies had the honor of eating with him and where they were chosen at each meal; the candlestick which he had held for him each evening at bedtime by a courtier whom he wished to honor, and always from among the most worthy of those present, whom he named aloud upon coming out from saying his prayers. Louis XIV carefully trained himself to be well informed about what was happening everywhere, in public places, in private homes, in public encounters, in the secrecy of families or of [amorous] liaisons. Spies and tell tales were countless. They existed in all forms: some who were unaware that their denunciations went as far as [the King], others who knew it; some who wrote him directly by having their letters delivered by routes which he had established for them, and those letters were seen only by him, and always before all other things; and lastly, some others who sometimes spoke to him secretly in his cabinets, by the back passageways. These secret communications broke the necks of an infinity of persons of all social positions, without their ever having been able to discover the cause, often very unjustly, and the King, once warned, never reconsidered, or so rarely that nothing was more [determined] ... In everything he loved splendor, magnificence, profusion. He turned this taste into a maxim for political reasons, and instilled it into his court on all matters. One could please him by throwing oneself into fine food, clothes, retinue, buildings, gambling. These were occasions which enabled him to talk to people. The essence of itwas that by this he attempted and succeeded in exhausting everyone by making luxury a virtue, and for certain persons a necessity, and thus he gradually reduced everyone to depending entirely upon his generosity in order to subsist. In this he also found satisfaction for his pride through a court which was superb in all respects, and through a greater confusion which increasingly destroyed natural distinctions. This is an evil which, once introduced, became the internal cancer which is devouring all individuals—because from the court it promptly spread to Paris and into the provinces and the armies, where persons, whatever their position, are considered important only in proportion to the table they lay and their magnificence ever since this unfortunate innovation—which is devouring all individuals, which forces those who are in a position to steal not to restrain themselves from doing so for the most part, in their need to keep up with their expenditures; [a cancer] which is nourished by the confusion of social positions, pride, and even decency, and which by a mad desire to grow keeps constantly increasing, whose consequences are infinite and lead to nothing less than ruin and general upheaval.