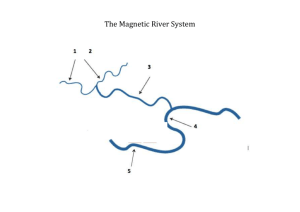

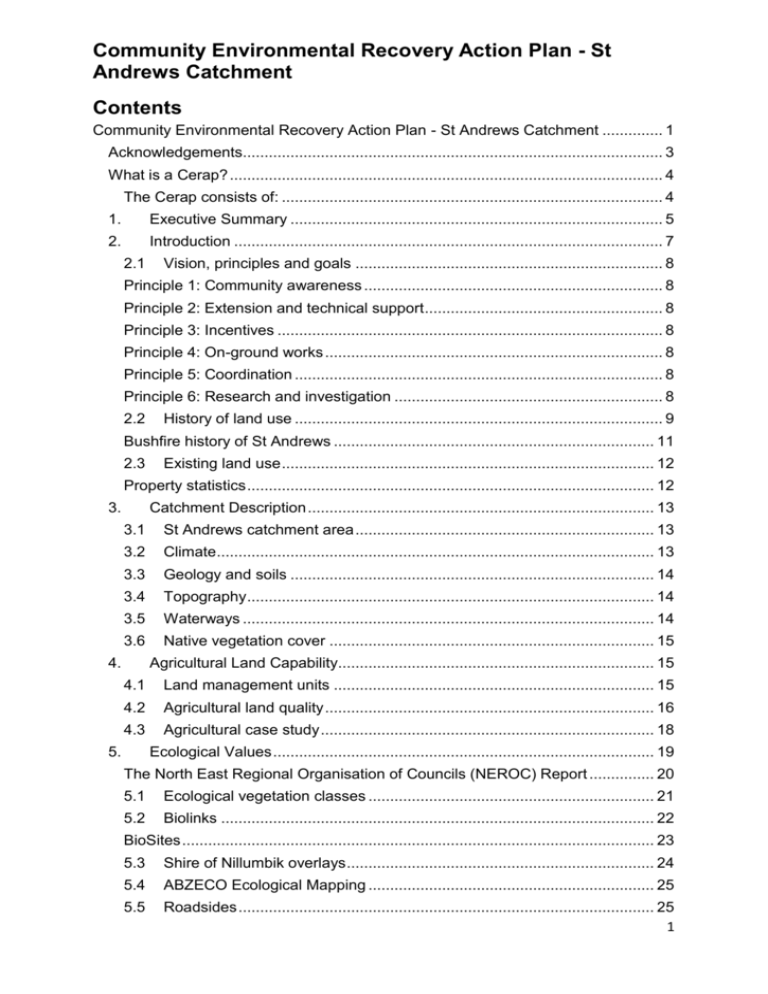

St Andrews Catchment - Nillumbik Shire Council

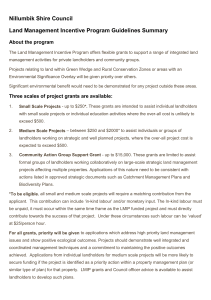

advertisement