Illuminate More Than Hide – costume in A

advertisement

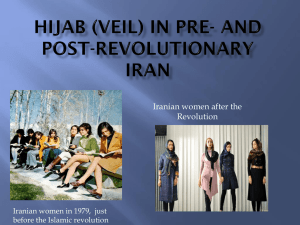

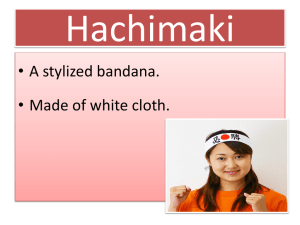

Illuminate More Than Hide: Costume Design in A Separation Kelsey Osgood examines the religious and cultural significance of costume design in 2012 Oscar winner for Best Foreign Language Film, A Separation (directed by Asghar Farhadi). Perhaps for many observers, particularly those who live in liberal Western cultures, the concept of Arab and Persian religious uniform is symbolised by the simplicity of the black burqa. The pious pare down their clothing to the least colourful and individualizing garments in order to humble themselves before their God. As generally decreed by feminist scholars, women in religiously observant societies are those most affected by sartorial limits. But like most practices viewed as wholly restrictive, the rules of modest dress for religious women and the way these women operate within this system, often illuminate more than they hide. Instead of eradicating choice, these limits highlight it; the echoes of the smallest fashion decision reverberate in costume, even for the Chasidish or Muslim female. Iranian produced and set A Separation (original title Jodaeiye Nader az Simin, costume design uncredited) has much to say in regards to even the subtlest of sartorial differences. In the film’s second scene, Simin (Leila Hatami), is packing belongings and moving in with her parents because her husband Nader (Peyman Moadi), refuses to leave Iran in order to grant their daughter Termeh a more liberated life. The final shot of Simin’s departure is simple: a steady profile as she drives away from the family home wearing a hijab and sunglasses to shield her eyes from the Tehran sun. These sunglasses are brown plastic with big, rectangular lenses. Nothing terribly noteworthy, but there is one remarkable thing about them: the arms are inscribed ‘Ray-Ban’. Already this well-known brand name has communicated a great deal about Simin’s character. We now know Simin is middleclass, modern and adventurous, or certainly she wants to appear that way. Simin’s clothing is contrasted with that of Razieh (Sareh Bayat), who has come to interview for the position of sitter (not nursemaid) for Nader’s senile father. Whereas Simin’s outfit, aside from the head covering, could pass for that of a Bryn Mawr sophomore, Razieh’s is in what Westerners regard as typically Islamic garb. Her hijab – black and without embellishment compared to Simin’s fern-coloured one in crepe de chine – is carefully folded so as to not reveal even a sliver of her neck or stray strand of hair. We at once identify Razieh as the oppressed as opposed to enlightened woman. Indeed, even Razieh’s facial features are more stereotypically Arab, while Simin with her sharp cheekbones, light complexion and red hair peeking beneath her hijab, looks outwardly Aryan. Razieh listens timidly as Nader explains the tasks that comprise her job. Next to Razieh’s mournful figure stands her four-year-old daughter Somayeh, who wears a white hijab; more child-friendly and easily held in place thanks to an elastic insert. Throughout A Separation, the hijabs and chadors (enveloping cloak worn on top of the hijab that is usually long enough to reach the ground) of the women appear to be perched precariously on their heads. Oftentimes, they do not wrap the long ends of the scarves around their necks but allow them to dangle toward the ground, as if mimicking Rapunzel-esque locks of hair. Very occasionally they even use this fabric as a prop for dramatic effect. When Simin storms out after a particularly intense row with her husband, she takes one end of the coloured hijab and tosses it over her shoulder, similar to the way a teenage Westerner may “flip” her tresses to assert dominance. It is thrilling and a little scary to watch these thin pieces of cloth threaten to whip away and leave a woman’s hair uncovered. Of course, not all women are subservient; of course jeans are allowed; of course they can wear Ray-Bans (these sunglasses have a long history in Iran. They were so popular, particularly in the port city of Abadan that in the southern region of Iran, “ray-ban” became a generic term for sunglasses). Indeed, the female characters in A Separation are the most mesmerizing. Part of the reason why is the clothing these women wear and the attention it draws. In attempting to subsume and blot out the female form, in many ways the traditional Muslim tenet to cover the body with as many layers as possible paradoxically results in emphasising the figure underneath. Consider Simin’s hijab or when Razieh departs the house (an apartment in a block) after her altercation with Nader. In the latter scene, Termeh (Sarina Faradi), a perceptive young girl, opens the door and sees from above Razieh as she rushes down the stairs, her long black chador streaming behind her. The chador rippling in the air gives Razieh the appearance of a boat’s wake as it speeds through water. These women therefore, who ought by religious and civil law to be as close to nonentities as possible simply by virtue of their dress, become society’s most compelling figures. Furthermore there are clues to the lives of these women hidden within their clothing: the nearly-indigo hijab worn by cold Simin as she confronts Nader, the layers of what looks to be hospital swaddling that a shameful and afraid Razieh wraps herself in during a altercation with her husband, the deep blue school uniform worn by Termeh, even a glimpse of signature Burberry plaid lining in a teacher’s jacket. The variety of dress worn by a group considered to be oppressed in a country known to be the harshest of theocracies upholds in this case the film’s thesis: that life, wherever and whenever, is complicated, unpredictable, and above all, layered.