23 Ahmed

advertisement

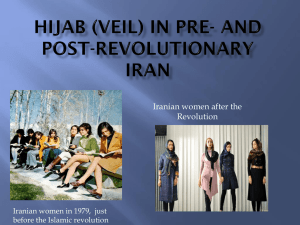

The Fall and Rise of the Veil: Leila Ahmed “When I wear this dress, people on the street realize that I am a Muslim woman, a good woman.” (Sociology 156) Islamism at the University • Free education means enrollment skyrockets – 1970: ~200,000 university students, 1977: ~500,000. Number of female students rises almost twice as quickly as male • Overcrowding results in mass transit & lecture halls, placing women, many from rural areas, into uncomfortably close environments with men, subject to harassment (77) – By 1975, Islamist groups gained control of important campus committees, becoming able to distribute literature at low cost, soon come to dominate student organizations • The hijab begins to appear on university campuses, and is initially mostly confined there – An “internal transformation” as women separated themselves from mainstream society via unique dress and strict observance of Islamic tenets and rituals – Goal to bring about governance based on Quran and Sunna, rejecting intervening Islamic scholarship as deviance & encrustation of original message • Oppose “Communism, Zionism, & Feminism” • While the Brotherhood had advocated a domestic life for women, they now operated “side by side” with male activists (77-82) 2 Islamism at the University • These organizations belonged to the broad mainstream of nonviolent Islamists – Hijab, language of “brother” and “sister” – In addition to hijab, women adopt ziyy, or zia Islami forms of dress, worn in limited array of fashions and somber colors – Erases social and class distinctions, reinforces commitment to egalitarian principles – “Unmistakably modern Islamic dress, devised in styles and materials that signaled at once the modernity of its wearers and their Islamic commitment.” – Also signals a commitment to a different form of Islam & Islamic society from that of surrounding culture • Women so dressed “appeared to be ‘sitting in judgment’ on their society and ‘critical of the way it appears to be going.’” • Society, families initially respond with alarm: “It is not even Islamic.” The veil “truly the greatest enemy of civilization and progress” (82-85) 3 Islamism at the University • Islamic dress adopted mostly be female students intending to become professionals – El Guindi: The woman who takes up the veil “‘is liberating herself . . . . by choosing to veil and not to be molested or stopped’ as she enters public space.” – 19% say they wear hijab to avoid harassment, 20% say it brings them new respect. (87) • “In contrast to the Iranian regime, which imposed veiling, the quiet revolution that the Sunni Islamists were setting in motion in Egypt was seemingly rather implanting in women the will and desire to wear hijab.” (116) 4 “A quiet conversion to a new way of life” • As many as 4,000 mosques built in Egypt by the 1980s • Fashion on the street changes – “Some men took to wearing beards as well as baggier, looser clothes and long shirts, sometimes even djellabas.” – Veil spreads from universities into the mainstream • “For Islamists, the hijab’s growing presence was doubtless an encouraging sign of their spreading influence.” • Why were women taking on the hijab? • Driven forward by women due to their own desires, or pressure from male leadership? (118-119) – Macleod & Zuhur 5 Macleod • All of the women in Macleod’s study (1983-88) had begun to wear hijab as adults • “Some said that there was a ‘general sense that people in their culture were turning back to a more authentic and culturally true way of life.’ Others said that in the past people had been ‘thoughtless and misled’ and now realized that their behavior had been wrong.” – 60% said they “simply did not know” why the change was happening • In initial interviews, Macleod finds some fine peace as a result of wearing hijab • Others did so to avoid harassment: “When I wear this dress, people on the street realize that I am a Muslim woman, a good woman. They leave me alone and respect me.” (120-121) 6 Macleod • No observable increase in religious observance among veiled women – Most, veiled and unveiled, “seldom performed any religious actions or indicated personal religious emotions” except at holiday & during Ramadan – Nonetheless, commitment to Islam “strong and unquestioned . . . . [the] foundation of their lives • Decision to veil typically involved resolution of problems in personal lives – Husband jealous of male attention – Balance responsibilities at work & home • “I want to quit my job but we need the money. When I wear this dress it says to everyone that I am trying to be a good wife and mother. The higab is the dress of Muslim women and it shows that I am a Muslim woman.” • The hijab “had now become a ‘culturally available’ way by which women could resolve tensions about their roles and make the statement that they were ‘good Muslim women.’” • Macleod rejects the notion that the hijab connotes anti-Western sentiment or extremist agenda (121-123) – Nonetheless, there was a heightened social concerns with religious matters. 7 Macleod • Veiling primarily a “voluntary movement” clearly “initiated and perpetuated by women” • But by 1988, growing social pressure to wear hijab – Women report they begin to wear it due to family pressure & to avoid constant harassment in public that accompanies Western dress • Generation gap: hijab more common among younger women – Veil “less one option among many and more the right thing to do,” possibly initiated by women but co-opted by men ((124-25) 8 Zuhur • In 1988, Zuhur finds no difference between veiled & unveiled women on roles of men & women – Different but complimentary – Equal opportunity & equal under law so long as sharia respected – Saw Islamist critiques of the West as meaningful • But non-veiled women did not see Islamist gov’t as desirable alternative, while veiled women “emphatically did.” – Implication that hijab worn not only to resolve personal conflicts, but also to signal support for Islamism – Attracted to “its association with cultural authenticity, nationalism, and pursuit of ‘adala, or social justice.” • Both groups equally pious, but unveiled have an emphasis on “inner” qualities of religion, veiled emphasize “outward,” visible qualities – “Since I veil, I am religious.” – Are unveiled women secular? (126-128) 9 The Veil • “Islamist male leaders conceived of veiling as strategically important to their movement.” – Gender segregated lecture halls & transport helped to spread “Islamist notions and practices of correct dress and norms of gender segregation.” – al-Aryan: “When the number of women students wearing the veil rises, that is a sign of resistance to Western civilization and the beginning of iltizam [pious commitment] towards Islam.” • The veil, like mass gatherings, made “visible to the dominant society the presence of people committed to an ethos and vision that was different from and seemingly implicitly oppositional to mainstream society and the reigning political order.” (132-135) 10 Islamist views of women • From survey of literature – Before the 1970s, the Muslim Brotherhood did not seek to involve or recruit women • Muslim Sisterhood mostly charitable concern – In the ‘70s & after, an increased concern with women – Women qualify for armed jihad, but disagreements over when it is an obligation for them – Activism acceptable if it does not disrupt the household or interfere with women’s domestic responsibilities • May hold any position other than head of state or Grand Imam – Families must be headed by men, women devoted to childbirth and rearing due their “special nature” • Realizing the advantages of having female activists for promoting Islamism, Islamists look to mobilize women (136-38) 11 Flipping the Narrative • Female activists part of a vanguard, exempt from “many of the rules of Islamic feminine orthodox behavior” until ultimate Islamist goals achieved (136-38) • “Women were ‘reminded of the degradation heaped upon them as a result of the economic imperialism of the West’ and were cast at once as ‘heroines and defenders of the fabric of Islamic society,’ and as at the center of a ‘regenerative effort to restore’ the Muslim world.” – Turning orientalist stereotypes against the West, saying opposition to the veil was part of the West’s effort to humilate & dominate the Muslim world – Paints Egyptian feminists as un-Islamic, Western (138-39) 12 Rising Violence • Through the 1980s & ‘90s, Egyptian Islamists come to control influential professional associations – Gov’t, to compete w/Islamists, emphasizes religion more and more • Returning mujahedeen from Afghanistan leads to spike in violence – Assassinations, church burnings – Farah Foda, Muslim supporter of secular gov’t, murdered – Islamist theorist al-Ghazali, who had previously been against violence, argues for the defense at trial of killer, saying that “anyone who resisted the full imposition of Islamic law was an apostate who should be be killed either by the government or by devout individuals.” • Islamist lawyers harass non-Islamists • Islamic Jihad (led by al-Zawahiri) massacres 60 tourists at Luxor in 1997 (142-144) 13 Spread of Islamism • Islamist militants become deeply unpopular • Legitimates high levels of gov’t repression • Gov’t bans hijab for girls grades 1-5, allows on middle school girls w/written consent from parents – Terribly unpopular, showing that “for girls and women, the hijab and the teachings of conservative forms of Islam (that is, the practices of Islamism) had become the normative, expected, and even desired practices for many.” • What 20 years before had been the practices and beliefs of fringe groups “had pervasively become, by the mid-1990s, the ordinary, normal practices of the majority of Egyptians.” (146-47) 14 State Repression • Across the 1990s, gov’t antiterrorism campaign “degenerated into indiscriminate state repression. More than 20,000 Islamists were imprisoned . . . many of them had been detained without charges and subjected to torture.” – Restrictions on press, military courts – Threat of imprisonment for association with any Islamist group, even if nonviolent • Especially the Brotherhood (151) • High levels of chronic coercion signals weak state 15 Why does Islamism grow in popularity in the face of repression? • Unlike militant Islamism, not just against status quo but for a better alternative • Valuable social networks • “Embodies many of the same hopes and aspirations –for freedom from dictatorship and for social justice and public accountability” that have inspired other movements • A form of empowerment for young people, who can critique their elders from a religious standpoint • Powerful forces of peer pressure & powerful social coercion – “Isn’t it proper, following the path of the Prophet?” • A demand for social & political activism, political optimism – Contrasted with a politically quietist pessimism common among nonIslamists (150-156) – Weber’s active asceticism: the believer as God’s tool 16