Antitrust Fairness: Economics and Philosophy Intertwined

advertisement

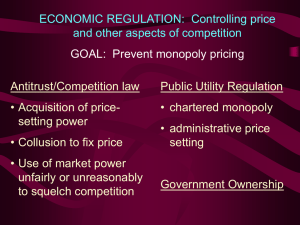

Antitrust Fairness: Economics and Philosophy Intertwined Adi Ayal1 - Antitrust is commonly assumed to be simultaneously efficient and fair, implicitly taking consumers as in need of, and deserving, protection The common view of antitrust is misleading in its simplicity, and ignores many real-world complications Monopolists, as well as consumers, may have justifiable claims that require assessment prior to intervention In order to adequately assess the claims of all parties involved, antitrust should include a context-dependent balancing test Introduction When competition professionals discuss fairness, they usually refer to the protection of consumers beyond that afforded by the objective assessment of economic efficiency. Antitrust is usually justified as protecting both efficiency and fairness, as competition achieves both. Monopolies (and anti-competitive phenomena more generally) are usually described as creating a surcharge over the competitive price, thus both transferring wealth away from consumers and imposing a deadweight loss on society. The first effect is seen as unfair and the second – inefficient. On the rare occasions when this link breaks down, it is because economic efficiency might dictate leniency towards anticompetitive actions (for example, in order to allow for firm growth and economies of scale). Fairness, on the other hand, is argued to dictate the protection of consumers from exploitation even when society might be paying an economic price. I hope to show that this commonly-held view is mistaken and misleading. This note shall begin with a summary of the standard view, present some exceptions to the rule, and then move on to argue for a re-thinking of implicit assumptions and accepted analysis. It then presents an alternative standard to guide the application of fairness in antitrust – one more coherent with a broad conception of the rule of law and constitutional standards. Of course, this will be merely an outline, and interested readers are referred to a more complete treatise where the argument is made in full.2 1 Faculty of Law, Bar llan University. PhD (Economics, UC Berkeley), PhD (Law, BIU). Comments always welcome! adi.ayal@biu.ac.il 2 Adi Ayal, Fairness in Antitrust: Protecting the Strong from the Weak (Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2014) Common Wisdom and Common Mistakes To begin, let us examine the standard graphical explanation of the need for antitrust, from both an efficiency and fairness standpoint: Figure 1 P S היצע Rent-seeking rectangle pm pc - עודף צרכן Deadweight Loss D qm qc ביקוש Q The basic idea is simple and familiar: the monopolist profits from raising prices above the competitive level (from pc to pm), but this causes consumers to reduce consumption (from qc to qm). Thus, the checkered triangle represents deadweight loss - products never made or sold, despite the fact that they cost less to produce than their value to consumers. The total loss of products forgone is borne by society as a whole, consumers and producers alike. This is easily demonstrated by focusing on the horizontal line at pc which cuts the triangle into two: the top half showing lost consumer surplus (benefit from purchasing at pc what consumers would have paid up to D), and the bottom half showing producer surplus (profit from selling at pc what cost S to produce). The striped rectangle represents the extra profit made by monopolists by raising price, essentially transferring what would be consumers' surplus in competition, to themselves. Thus the rectangle is usually referred to as a 'wealth transfer', representing the inherent unfairness of monopoly. Beyond the fairness problem, the wealth transfer rectangle is problematic from an efficiency viewpoint as well: since producers can anticipate the additional profit awaiting those successful at achieving monopoly, they would rationally invest in the race. Obviously a gross simplification for explicative purposes, but the rectangle can be seen as representing gains from monopoly (subtracting from it their lost share in the deadweight triangle) and thus also the amount worth investing by firms seeking monopoly rents.3 3 Of course, these investments might also turn out to be welfare-enhancing in part, such as innovative processes and products created by what Joseph Schumpeter described as a process of 'creative destruction' whereby firms race to achieve monopoly, displacing previous market leaders and replacing older technologies with new. See, Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, (2nd edn. New York: Harper & In general, measuring the welfare gains and losses stemming from monopoly is easier in theory than in practice, with prominent scholars disagreeing even on the basic question whether the benefits from having an antitrust policy outweigh its costs. Dennis Carlton, while serving as Chief Economist for the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division, stated "no comprehensive study yet exists that quantifies the benefits (or costs) of our current antitrust policies compared to other possible policy regimes".4 There exist multiple scenarios where competition may be welfarereducing, as economic circumstances sometimes dictate the advantage of size, experience, stability, or even the ability to plan and adapt to changing circumstances.5 Since this note focuses on fairness, we shall not delve into the intricacies of efficiency analysis, and the countervailing effects that competition entails. Furthermore, the discussion of fairness in antitrust is much broader than the question of monopoly profit or wealth transfers. Still, as Figure 1 represents the perceived common wisdom regarding competition policy, I focus on it first, and note its limitations. The graph represents allocative (or static) efficiency, while ignoring dynamic effects such as productive efficiencies and innovation. But while these are regularly scrutinized by economists and form an important part of every antitrust proceeding, one assumption remains implicit and unchallenged: that the wealth-transfer rectangle represents an unfair taking of consumer surplus, one that antitrust should correct. It is this basic truism that we now tackle. The (Un)Fairness of Monopoly Profit The very term “wealth transfer” creates a mental picture of monopolists taking away wealth that belonged to consumers, akin to theft.6 The graphical representation in Figure 1 makes this mental picture clear, as the size of the transfer seems measurable, and the competitive price seems to benchmark precisely the allocation of surplus between producers and consumers. Anything above the pc-line “belongs” to consumers, and is deemed “consumer surplus” in all economic textbooks, and anything below it is similarly viewed as “producer surplus”. Bros., 1947), Ch. 8. For a recent exposition of Schumpeter's scholarship and intellectual development see, Thomas K. McGraw, Prophet of Innovation: Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction (Harvard University Press, 2007) 4 See, Dennis Carlton, ‘Does Antitrust Need to be Modernized?’ (2007) 21 Journal of Economic Perspectives 155, 174. A good example of the problem can be seen in the Fall 2003 volume of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, where Jonathan Baker debated this issue with Robert Crandall and Clifford Winston, with both sides presenting compelling cases for opposite results. 5 See, e.g., Donald Dewey, ‘Information, Entry and Welfare: the Case for Collusion’ (1979) 69 American Economic Review 587; S.Y. Wu, ‘An Essay on Monopoly Power and Stable Price Policy’ (1979) 69 American Economic Review 60; Dennis W. Carlton, ‘Market Behavior with Demand Uncertainty and Price Inflexibility’ (1978) 68 American Economic Review 571. Similar dynamics can create incentives for vertical integration or the creation of supplier networks, see, Rachel E Kranton and Deborah F Minehart, ‘Networks versus Vertical Integration’ (2000) 31 Rand Journal of Economics 570 6 Viewing wealth transfers as theft is implicit in most analyses of antitrust, as shall be show, but sometimes made very explicit. See, e.g., Robert H. Lande, ‘A Traditional and Textualist Analysis of the Goals of Antitrust: Efficiency, Preventing Theft from Consumers, and Consumer Choice’ (2013) 81 Fordham Law Review 2349; Gordon Tullock, ‘The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft’ (1967) 7 Western Economic Journal 224. The one thing that is ignored in all these analyses is that the surplus cannot exist without trade taking place, and such trade depends on contractual agreement of both sides. Viewing consumers as having a right to “their share” of the surplus, essentially divides it between the parties before it exists. To see why this is so, imagine a monopolist offering consumers a deal whereby they agree to the monopolistic price (pm) and he agrees to sell them a monopolistic quantity (qm) of the product. Before the contract was struck, no product existed (indeed, none could exist, given that the producer is assumed to be a monopolist). Before the product exists, there is no surplus, thus side could argue that they deserve a certain share of it. Even after the product is made by the monopolist, the surplus itself does not yet exist, as it is the result of trade – moving the product from the party valuing it less, to the party valuing it more. The former are producers, whose valuation stems from the costs invested in production, and the latter are consumers, whose valuation stems from the use they make of the product. The surplus is thus created by trade. Once trade is carried out, the product “moves up” in the chain of valuation, or as economic textbooks put it: “gravitates towards the most efficient user”. What is important to note, is that the same trade which creates the surplus, also divides it. Thus, consumer surplus is that which remains in their hands after payment of the sum to which they agreed. Whatever the price, monopolistic or otherwise, it stems from contractual agreement and determines the allocation of surplus a-priori. In any contract, price is a substantive term without which no agreement to trade exists. Assuming a right to a certain share of the surplus thus assumes the existence of trade without it including a price term, a preposterous proposition anywhere outside of antitrust. There are two general strands of thought substantiating counter-arguments to the above view: the first positing a right to consume at competitive prices, and the second focusing on the creation of markets, rather than their resulting price. The Right to a Competitive Price It is common in competition analysis to assume that consumers deserve to buy at competitive prices, whether this assumption is stated explicitly, or remains implicit in the use of the term “wealth transfer”. But what remains unspoken is the associated truism: prices in competition are determined by supply and demand, and the size of each parties’ surplus depends not only on price, but on their associated elasticity. To see the point, note the differences between Figure 2 and Figure 3 below: Figure 2 P p2 Added Revenue p1 Forgone Revenue D ביקוש q2 q1 Q Figure 3 P Added Revenue p2 Forgone Revenue p1 D ביקוש q2 q1 Q The difference between the representations lies in the slope of D, the consumers’ demand function. In Figure 2 the slope is relatively gentle, while in figure 3 it is relatively steep. This slope signifies the consumers’ elasticity of demand, i.e. their willingness to forgo consumption of the good once its price rises. The two figures show clearly that a similar price raise is associated with markedly different reductions in quantity demanded, thus leading to dramatic differences in the revenue forgone by a monopolist raising prices in each case. Consumers represented in Figure 2 have relatively elastic demand, thus raising the prices they face is on one hand less profitable for the monopolist, and on the other hand more harmful for society. Consumers in Figure 3 have relatively inelastic demand, thus will continue to consume at the higher prices, making the price raise more lucrative from the monopolist’s point of view, and less harmful aggregately. If we similarly include the producer’s elasticity of supply, we see that “competitive price” is not a clear determinant of how much each party to the trade profits, but can result in markedly different divisions of surplus. In other words, the same standard of competitive price can lead to great (or small) profit for producers (or consumers). It is far from sufficient as a substantive measure of welfare. Beyond the distribution of surplus, assuming a right to competitive prices is problematic from another aspect: that of forced labor. Assume that a monopolist does not wish to produce or sell at competitive prices. Endowing consumers with a right to purchase at competitive prices essentially forces producers to comply, preventing them not only from raising prices directly, but from restricting output in order to indirectly affect prices. It follows that producers generally, and monopolists in particular, must produce the competitive quantities – forcing them to do with their property that which they prefer not to.7 Forcing producers to produce is the extreme example of ignoring their rights while extolling those of their consumers, and will be returned to below when discussing monopolists’ rights. Before moving on, though, let us examine a more refined version of consumer protection in antitrust, that of the right to competitive markets (rather than prices). The Right to Competitive Markets Rather than focus on the prices resulting from competition, one could focus on the competitive process itself. This way, neither producers nor consumers deserve a certain price, but must be content with whatever they can muster in a competitive market. Consumers cannot argue that they have been cheated out of surplus belonging to them prior to trade taking place, but can complain of harm to their right to a process determining the resultant terms and conditions – including price. Focusing on consumers’ rights is paramount in the discussion of fairness in antitrust, as the very term connotes protection of just desert claimed by an individual who might be harmed. In this, fairness is different than efficiency or societal goals more generally, since the latter focus on aggregate concerns. For example, one could promote competition in order to further economic growth or induce innovation, but these would be justified on grounds of aggregate welfare and raise no fairness concerns. While much of antitrust focuses precisely on such issues, the inherent unfairness of monopolistic practices is taken as obvious, whether explicitly spelling out the consumer protection issue or assuming it implicitly. What, then, is so obvious about the right to a competitive market, especially given that these are often lacking in realistic settings? Competitive markets should not be assumed to arise naturally. Reality is complex, as are natural and societal endowments of wealth and ability, scale economies in production, relative advantages in trade, and a myriad of other characteristics which lead to economic concentration. If competitive markets are viewed as necessary from a fairness standpoint, it is because they are called for by something in human nature, or the nature of society we want to live in. One of the most influential attempts to spell out criteria for social rules and the just principles that underlie fairness, is that of John Rawls’ veil of ignorance.8 There, Rawls posits that any notion of fairness should avoid relying on subjective valuations and chance occurrences, such as being born to a particular social standing or circumstance. He suggests a simple thought-experiment whereby we 7 The argument seems extreme in these circumstances. For elaboration and discussion beyond the antitrust context, see, Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (New York: Basic Books, 1974) 169-170 who argues vehemently against it. For acceptance of the forced labor result, see Richard J. Arneson, ‘Property Rights in Persons’ in Economic Rights (Ellen Frankel Paul, Fred d. Miller and Jeffrey Paul, eds., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). 204-206. 8 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, Revised edn. (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1999). Interestingly a similar account precedes Rawls, though the details differ, see, Friedrich A. von Hayek, Law, Legislation, and Liberty, Vol. 2 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976) 126-128. There, Hayek describes ‘abstract rules of just conduct’ as affecting chances of success alone, with no claim for specific results being justified: "we should regard as the most desirable order of society one which we would choose if we knew that our initial position in it would be decided purely by chance (such as the fact of our being born into a particular family)", ibid. 132. imagine ourselves viewing society from without, knowing all worldly effects of proposed rules – but not knowing which member of society we are. Thus, a veil of ignorance separates those deciding on the rules from those being affected by them. If each of us could imagine our decision-making behind the veil of ignorance, we would choose rules based not on their effect on us (of which we are ignorant), but on their effect on each member of society (which might turn out to be us). Similar to two brothers forced to share a cake, “I cut, you choose” is a just procedure ensuring a just division.9 Once the decider of rules is divested from his own subjective preferences, or is unable to know whether an unequal division will benefit or harm him, the resultant rules are expected to be chosen fairly, taking all people and circumstances under consideration. In the context of economic rules, this means that the Rawlsian criterion leads to principles of fairness where all could participate in the spoils of trade – presumably justifying competitive markets. There are many aspects to the fairness argument for a right to competitive markets, and many caveats and counter-arguments to be considered. This short note is obviously not the place to delve into details, and I refer the interested reader to the book for elaboration. Still, one should note that competitive markets are not necessarily good for all involved. Some consumers are endowed with more material wealth than others – and will thus attain more. Competitive supply and demand schedules can differ in their elasticity, and thus more or less surplus is retained for producers and consumers (both between the groups and among each of them). Some competitors are unable to achieve sufficient scale for efficient production, and will thus be priced out of the market. In short – there is nothing ‘protective’ about competition. On the contrary, competitors’ economic lives under the constraint of having to meet fluctuating standards and tastes are often “nasty, brutish, and short”.10 The argument for a right to competitive market merits more detail than can be afforded it here, and depends to a large extent on our conception of property in sometimes counter-intuitive ways. I shall not attempt to review the entirety of the argument here, but will point out important counter-claims often ignored and completely lacking in the antitrust debate: that of the rights of monopolists. The Rights of Monopolists Monopolists are not usually seen as bearers of rights, as is made clear by the abundance of claims that antitrust protects consumers versus the dearth of anything resembling a credible claim for the right to monopolize or attain monopolistic profit. Of course, litigants have rights, and monopolistic firms are able to claim court protections regarding procedure, confiscation, and reliance. Still, the basic claim that consumers have a right to competition is rarely juxtaposed with a counter-claim for monopolists’ right to profit. Yet there are two basic sources that might justify such a right: freedom of contract, and the right to property. Freedom of contract was alluded to above, when discussing the division of surplus. Since trade is the result of contractual agreement, one could argue that any surplus attained by either party to a transaction is fair, as both agreed to it. Of course, one could argue that contractual acquiescence is insufficient, since the consumer might have been coerced and lacked relevant alternatives to the monopolized product. Yet that would be an extreme argument appropriate for some circumstances and not others. Monopolized milk or bread might warrant an 9 Though this is true only in the abstract, and various limitations on the model prevent its application. See chapter 6 of Fairness in Antitrust, note 1 above, for discussion and application to the antitrust scenario. 10 Paraphrasing the Hobbesian account of a “free” life without the benefit of a despotic ruler. See, Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Schlager Publishing, 1651). assumption of coercion, but monopolized diamonds less so. Were antitrust to be context-specific, in that basic goods would be protected more than luxury items, the contractual coercion argument might have some merit. But that is not the case. Antitrust is mostly applied as context-free, limiting the monopolization of necessary and extravagant items alike. Similarly, monopolists (or those involved in anti-competitive concerns) can be large or small, wealthy or financially struggling, privileged or up-and-coming. All types are similarly constrained by rules of antitrust which determine the types of transactions allowed, as well as those scrutinized or forbidden outright. A monopolist claiming his freedom of contract was infringed upon when not allowed to determine the terms of trade, would be laughed out of court. Similarly, the right to property is thought to include within it a right of disposition which contains not just the right to do with the property as one desires, but a right to profit from it as well. The monopolists’ right to their property is respected insofar as governmental takings are concerned (a taking would generally be compensated), but only outside of the sphere of antitrust. One might entertain an idea that if society wants to limit monopolistic practices in order to attain superior growth, innovation, or distribution of resources, it should compensate those whose freedoms were infringed upon. Such an idea would be well-accepted within the property rights discourse, but would be rejected out of hand (if considered at all) in any discussion of modern antitrust.11 Of course, one need not accept monopolists’ cry for protection at face value, and we should differentiate between principled arguments and self-serving claims. Still, it is interesting to note how little discussion exists in the literature of antitrust regarding the rights of monopolists to be protected from rules which impose competition even where it never arose from market conditions. To the contrary, where natural monopoly conditions apply, commentators regularly assume the state should regulate producers or providers of necessary services. Even where monopolists created the market and no goods of the relevant type existed prior, the essential facilities doctrine steps up to ensure that the benefits accruing from privately produced and owned goods are distributed in a manner allowing competitor access and consumer gain. Even without delving into the many philosophical claims and counter-claims relevant to the monopolist rights issue, one may discern that antitrust allows for (indeed, relies on) a severely tilted view of the just desert of consumers versus producers. In any other field of law, limiting those with power in order to protect those without it is subject to limiting principles assessing the harm to each side before and due to intervention. Antitrust is currently blind to this issue. Let us then suggest a framework for addressing the concerns of both parties to the debate, consumers requiring protection and monopolists claiming relevance and requesting consideration. The Balancing Test for Antitrust Once antitrust is reconsidered along the lines suggested above, one need not accept all of monopolists’ claims are decide a-priori if their rights supersede those of consumers. All that is required is that monopolists are accepted as bearers of rights requiring consideration before limiting their conduct. In many cases, monopolistic conduct is harmful to others to such an extent that 11 See Jan Narveson, ‘Democracy and Economic Rights’ in Economic Rights (Ellen Frankel Paul, Fred d. Miller and Jeffrey Paul, eds., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992) for the general argument. For a rare (and much ignored) case of application to antitrust, see, Richard Epstein, ‘Private Property and the Public domain: The Case of Antitrust’ in Ethics, Economics and the Law, Nomos XXIV (J. Roland Pennock & John W. Chapman eds., New York: New York University Press, 1982) 57. society would rightly constrain economic power and impose competition on markets. In some cases, though, this might not be the case. The determining factor should not be the categorization of one party as consumer and the other as monopolist, but a more nuanced view allowing for the details of the case to determine its result. Since we are accustomed to present-day antitrust, it might be difficult to let go of our predisposed preference for consumers and disdain of monopolists, thus an example from a different field of study might be appropriate. Consider freedom of speech. Oftentimes, one group wishes to promulgate views to which others object, often citing specific harms that would come from allowing the first to state their case. Neither those claiming the right to speak their minds, nor those intent on limiting the speakers, have an absolute claim that will take precedence over the other. Speech is important, and the freedom to engage in it is one of the most basic democratic principles. Yet one’s free speech is another’s social harm. Important limitations on speech include one’s inability to spew hatred and incite violence, rules against slander and public indecency, and even limitations on educating the public on cryptography or bomb-making. In each case the protected interest of free speech is balanced against other protected interests, with the result determined on a case-by-case basis by courts weighing the pros and cons and assessing the level of harm befalling each of the relevant parties. Similarly to speech, antitrust operates in a context where one side is bestowed with a stronger claim and state intervention is skewed. Just as citizens are assumed to be entitled to a ‘free market’ of ideas and the right to speak freely, so are they allowed access to a free economic market and a strong right of participation. Still, a strong bias in favor of one side does not entail absolute protection. Monopolists are not always the economically-powerful mega-firms that common intuition assumes. Sometimes they are small and local businesses, with workers and local communities dependent upon them, and sometimes the ‘consumer’ is a powerful buyer interacting with many small providers. Even in such cases, the rules of antitrust forbid cartels, constrain mergers, and ignore monopolists’ rights. A balancing test for antitrust would take into account the different claims raised by each party, and protect consumers based on the justifiability of their claims. The difference would be that harm to monopolists from such intervention would be taken into account as well, contrary to current practice. Allowing claims of harm on part of monopolists would not destroy antitrust or do away with consumer protection. It would make it smarter, more context-dependent, and more in accordance with general legal theory and the philosophical underpinnings of what we call property. A balancing test would respect the fact that property is a fundamental right, yet one that can be limited in the appropriate circumstances. Balancing entails respect – to both parties to the debate. Those stressing consumer protection would still be able to state their claim, and win in court, they would merely be required to show that the monopolists in question are not ignored, and their limitation is justified due to the particulars of the case. Accepting a balancing test for antitrust requires a shift in thought, but will keep us intellectually honest and philosophically coherent. We should have to justify intervention while keeping in mind that there exist some who are harmed thereby, both in order to protect those deserving it and in order to force ourselves to consider even those we love to hate. Monopolists are far from perfect, but so are the rest of us. Rights entail respect, and antitrust has forgotten this basic maxim.