Constantine and Christianity in Rome

Constantine and Christianity in Rome

At its height, the Roman Empire counted among its citizens people of many races, who spoke numerous languages and followed many religious beliefs. Romans came to know different gods as new lands were added to the empire, and often included some of these gods among those they traditionally worshiped. Freedom of religion was generally allowed, if not by law, at least in practice.

There were numerous cults that flourished and gained followers. The Christian religion started as one of these, but with one important difference. Christianity promised something that other belief systems of the time did not: a chance of salvation and eternal life. Christians believed that their founder, Jesus

Christ, was not only a prophet, but also the son of God.

Because Christians put their God above all else—even the emperor—Rome’s rulers did not look favorably on them. From as early as A .

D . 64, Christians were punished by those in power. The bloodiest persecution came under the emperor Diocletian, who issued many edicts (decrees or laws) calling for

Christians to denounce their faith. However, because they believed that eternal life and salvation awaited them, Christians preferred to face death rather than give up their beliefs.

As a young soldier, the future emperor Constantine witnessed the persecutions and saw how

Diocletian’s attempts to destroy the Christians failed. At the same time, Constantine realized that loyalty, such as that shown by the Christians to their faith, would be extremely important for a growing empire. Legend has it that, as he prepared to battle his arch rival Maxentius, Constantine saw an unusual sign in the sky and heard the words, “In this sign thou shalt conquer.” Whether this story is true or not, Constantine did have his soldiers paint a sign representing the first two letters of Christ’s name on their shields. When he defeated Maxentius, Constantine resolved to repay his debt. After he was proclaimed emperor, he passed a law known as the Edict of Milan, which, for the first time in history, proclaimed freedom of religion as a fundamental right of every person.

When conflict arose within the church, Constantine was determined to settle the differences. In 325, he called for religious leaders to meet in the city of Nicaea. One result of this meeting was a document known as the Nicene Creed, a statement of faith that is still followed by Christians today.

Constantine was careful not to alienate those who continued to follow pagan beliefs. He believed that when imperial favor was withdrawn from the older religions, they would wither and disappear naturally. Thus he initiated much legislative reform—everything from laws for better treatment of slaves to proclaiming Sunday as an official day of rest. By decree, these laws applied to people of all faiths.

It was under the Roman emperor Theodosius I ( A .

D . 347–395) that Christianity became a state religion. Like Constantine before him, Theodosius knew that a strong church was key to a strong government. Theodosius became known as “the Great” after he passed an edict that commanded all people to follow the Christian religion. Those who refused to do so were considered heretics and punished.

Soon after Theodosius’ death in 395, the Roman Empire in the west fell. The Christian Church, however, continued to be a powerful entity and played a key role in history of western civilization.

Questions:

1. Who was Constantine?

2. Why did Constantine convert to Christianity?

3. In what ways did Constantine mix Church and State?

4. How did Constantine impact the history of Christianity?

Charlemagne and Medieval Christianity

Charlemagne could scarcely believe the splendor of the ancient city of Rome. As he traveled along the road to meet Hadrian I, the new pope, people waved banners to greet him. This was Charlemagne’s first visit to Rome, and he had come at the pope’s request for help. Little did he know that his relationship with Hadrian would last more than 20 years.

Since the fall of Rome almost 300 years earlier, the emperor of the Roman Empire had lived in

Constantinople — too far away to be very involved in matters affecting Western Europe. Charlemagne’s father, Pepin, had promised to protect Rome against the Lombards who kept threatening to overtake the city. Now Hadrian wanted Charlemagne to keep his father’s promise since Lombards were again encroaching on lands ruled by the pope.

Hadrian admired the strength and honesty of this rough warrior-king. He also sensed that

Charlemagne shared his love for the church. Charlemagne, on the other hand, was awestruck. Hadrian treated him to elaborate banquets and festivities, and even had a medal made commemorating their meeting. On one side were the figures of the two men, their hands placed on a Bible at an altar. On the reverse side, a Latin inscription read “Sacred League.”

Charlemagne firmly believed that he was sent by God to convert all Europe to Christianity. If that meant he must conquer people first, he did — even though thousands died as a result. Nonetheless, he dreamed of making the Roman church strong enough to serve the state. The clergy, however, had to be educated first and, for that, Charlemagne needed the pope. At Charlmagne’s request, Hadrian had copies made of church law and sent clerics to Frankland who could properly instruct the clergy there.

Unfortunatley, Hadrian died. The “Sacred League” was over. Grief-stricken, Charlemagne wept openly.

How could he make peace with his lifelong friend, the godfather of two of his children, and his ally in spreading Christianity? That day, by order of King Charlemagne, every church throughout the kingdom uttered prayers in honor of Pope Hadrian.

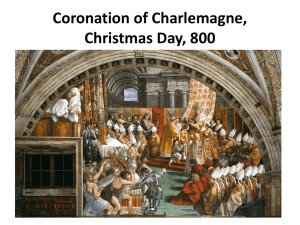

On Christmas Day in Rome, A .

D . 800, Hadrian’s successor, Pope Leo III, anointed Charlemagne emperor of the Roman Empire. When Leo placed a jewel-studded gold crown on Charlemagne’s head, the crowd cheered, “Charles Augustus, crowned by God!”

Scholars have discussed the meaning of this event ever since. For more than 300 years, the capital city and home of the Roman emperor had been Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul). Charlemagne’s coronation returned power to Rome. It also led to the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire, which lasted for 1,000 years.

Some call Charlemagne the father of European civilization. Charlemagne loved learning. He recruited scholars from all over Europe to establish schools, which eventually led to the establishment of

Europe’s earliest universities. Such great strides were made in the arts and literature during this period that it is called the Carolingian Renaissance. Scholars and writers were encouraged to record events and thoughts. Scribes hand-copied thousands of books (there were no printing presses yet), which preserved history and promoted literacy.

Most important, Charlemagne spread Christianity across Europe. Often he resorted to brutal warfare to do it: conquer the land, then convert the people. Yet he was remarkably successful and his policy changed history. After Charlemagne became Roman emperor, the eastern and western branches of

Christianity divided. The eastern branch had its base in Constantinople and the western in Rome. They remain separate to this day.

Questions:

1. Who was Charlemagne?

2. What was the “Sacred League?”

3. What was the effect of Charlemagne being crowned as a Holy Roman Emperor?

4. How did Charlemagne impact the history of Christianity?

Martin Luther and the 95 Theses

With marked determination, a Christian priest named Martin Luther tacked his “Ninety-Five Theses on the Power of Indulgence” to the Castle Church door. The year was 1517, and Luther was just following the custom of the time. The door of the church served as a bulletin board for Wittenberg University, and his theses were propositions for debate.

Thesis 1 said that a Christian’s life should be an ongoing act of penance, not something that took just one or two days. Thesis 43 said, “Christians are to be taught that he who gives to the poor or lends to the needy does a better deed than he who buys indulgences.”

Luther believed that it was not enough for a teacher of the church to proclaim the truth. A teacher must also point out error so that Christians would not be led astray and fall away from faith in God.

Thus, in many of his writings, Luther criticized the Roman Catholic Church of his day for practices and beliefs that he considered dangerous to the faith of Christians. He was especially critical when the church taught that God saves people not only for the sake of Jesus and because of what he had done, but also because of the good works that God’s children do. Although God certainly wants believers to obey him and to honor him with the way they live, Luther insisted that whatever good works Christians perform, these works in no way earn them God’s favor or salvation.

Luther did not agree with the church’s position on indulgences, and it was the ongoing Indulgence

Controversy that had thrust Luther into conflict with the church. At that time, the church taught that after a person sinned, he needed forgiveness for the sin. He also needed to make amends to the one who had been wronged or do good works to help someone else. While the church freely granted pardon for the sin, this pardon did not take care of penance (making amends). If the sinner neglected to do this penance, he would go to purgatory after death. The sinner would remain in purgatory until his sufferings were sufficient to complete the penance for past sins. Since the work of penance might be difficult and since no one wanted to go to purgatory, the church introduced the “indulgence.” By buying a letter of indulgence for a good work, a sinner could shorten his stay in purgatory. Such good works included giving money to build a church, support a monastery, or help an orphanage.

Two years after Luther posted his “Theses,” a debate was held in Leipzig, Germany. During the debate,

Luther said that both the pope, the head of the Roman Catholic Church, and church councils might make mistakes. Luther now faced the full implications of his “Ninety-Five Theses.” His opponents had made him declare publicly that the sole authority in matters of faith was neither the pope nor church councils, but scripture. In the years that followed, many more reformers followed Luther’s example and voiced their disagreement with church practices.

However, Luther was not the first person to criticize the Roman Catholic Church. Several hundred years before he was born, people had begun to question the corrupt practices in the church.

Some reformers wanted economic relief and were primarily concerned with reducing church-imposed taxes. In 1372, several papal tax collectors were imprisoned and killed. There were others who favored reform because they disliked the immorality and corruption of some church members. The third and the most effective thrust for reform was doctrinal. This movement was led by people who studied the

Bible. They believed that the scriptures, not the words of priests or popes, were the basis of faith and salvation. By Luther’s time and in the years that followed, many more reformers voiced their disagreement with church practices. In 1529, church and state officials met in Speyer, Germany, to discuss the religious problems facing the German nation. Luther’s followers were there, openly protesting an earlier decision that said German princes had the right to choose the religion the people in their area would follow. These protests led to their being called “Protestants,” a name now used to refer to Christians who do not follow the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church.