File - Ashley`s E

advertisement

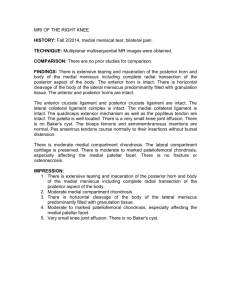

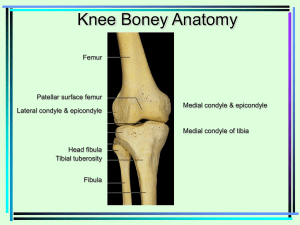

Ashley Tanner AT 3500 Unit 1 EBM The meniscus acts as a shock absorber and stabilizer in the knee. It is a wedge shaped structure between the femur and the tibia. It is made of fibrocartilage, which is pliable but very strong. The meniscus has a lateral and medial portion. Meniscal tears most commonly occur when the knee is flexed, weight bearing, and twisted. This happens most commonly on acceleration or deceleration. It can also occur as a patent gets older. The meniscus naturally wears with age, which can make it more susceptible to tearing. It can also be torn from repetitive movements such as running. There are five types of meniscal tears, longitudinal, bucket handle, flap, transverse, and a torn horn tear (Learmonth, D). The article comparing MRI findings to clinical examination findings (Atay OA. Et al.) showed that there was no significant difference between MRI or clinical examination in diagnosing medial or lateral meniscal tears. A well-trained qualified surgeon can safely rely on clinical examination for diagnosing meniscal injuries. A patient can present with several different signs and symptoms and have a meniscal injury. Some symptoms are purely mechanical, popping, clicking and catching within the knee joint. Other symptoms present as pain with knee flexion and pain when palpating the joint line. The gold standard for diagnosing meniscal tears is an arthroscopy. An MRI is also very accurate. As far as physical testing McMurray’s and Apley’s test are the gold standard. However, meniscal tears are best diagnosed when many tests are used. Thessaly’s test is performed by having the patient stand on one leg. The patient will bend the knee to 20 degrees of flexion, holding on to a table for support if needed. The patient will then rotate the femur on the tibia, twisting back and forth three times, maintaining 20 degrees of flexion. The test is positive if the patient has medial or lateral jointline discomfort, or a catching or locking sensation. The test should be performed bilaterally. In one test (Abel BE. Et al.) Thessaly’s test reported the following findings: Sensitivity = 90.3% Specificity = 97.7% Accuracy = 88.8% Another article (Atay OA. Et al.) looked at Thessaly’s test with the patient bending to 5 degrees of flexion and 20 degrees of flexion. They found that the test is considerably more accurate when the knee is bent to 20 degrees. They also compared the results of the tests for medial and lateral meniscus tears. The results were as follows: Medial meniscus at 20 Degrees Sensitivity = 89% Specificity = 97% Accuracy = 86% Lateral meniscus at 5 Degrees Sensitivity = 92% Specificity = 96% Accuracy = 94% Medial meniscus at 5 degrees Sensitivity = 66% Specificity = 96% Accuracy = 86% Lateral meniscus at 5 degrees Sensitivity = 81% Specificity = 91% Accuracy = 90% An article (Haddad FS. Et al.) examined the true positives, true negatives, false positives and false negatives of Thessaly’s test at 5 and 20 degrees. The test was divided into medial and lateral meniscus, and involved 109 patients. Medial meniscus at 5 degrees True + = 24 True - = 15 False + = 7 False - = 34 Lateral meniscus at 5 degrees True + = 35 True - = 14 False + = 7 False - = 24 Medial meniscus at 20 degrees True + = 3 True - = 54 False + = 7 False - = 16 Lateral meniscus at 20 degrees True + = 6 True - = 58 False + = 3 False - = 13 This article (Haddad FS. Et al.) showed that there are a significantly higher number of false negatives than false positives. The article also looked at the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictability, and the +/-LR. Medial meniscus at 5 degrees Sensitivity = 68% Specificity = 77% + predictability = 31% -predictability = 49% +LR = .9 -LR = 2 Lateral meniscus at 5 degrees Sensitivity = 89% Specificity = 30% + predictability = 77% -predictability = 71% +LR = 1 -LR = 1 Medial meniscus at 20 degrees Sensitivity = 59% Specificity = 67% + predictability = 83% -predictability = 37% +LR = 2 -LR = 0.6 Lateral meniscus at 20 degrees Sensitivity = 31% Specificity = 95% + predictability = 66% -predictability = 81% +LR = 6 -LR = 0.7 Palpating the joint line of the knee for tenderness, though simple, can be a very accurate predictor for meniscal tears. The article (Hantes M. Et al.) shows the specificity, sensitivity, false positive, false negatives, and over all accuracy for joint line tenderness for the medial and lateral meniscus. The study showed that joint line tenderness is very specific when testing for meniscal tears in both the medial and lateral meniscus. The sensitivity is also fairly good overall, but it is greater for the lateral meniscal. The false positives reported were about the same for both medial and lateral meniscus, but the lateral meniscus has a significantly lower amount of false negatives than when testing the medial meniscus. Medial meniscus Sensitivity = 71% Specificity = 87% False Positives = 8.8% False Negatives = 10% Overall accuracy = 81% Lateral Meniscus Sensitivity = 78% Specificity = 90% False positives = 9.3% False negatives = 2 % Overall accuracy = 89% The study done by (Haddad FS. Et al.) also examined the true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives when looking at joint line tenderness for meniscal tears. 109 patients were examined. Medial Meniscus True + = 53 True - = 13 False + = 5 False - = 11 Lateral Meniscus True + = 13 True - = 63 False + = 2 False - = 6 This same article (Haddad FS. Et al.) looked at the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictability, diagnostic accuracy, and the LR of +/-. The results were as follows: Medial Meniscus Sensitivity = 83% Specificity = 76% + predictability = 91% -predictability = 59% Diagnostic accuracy 81% +LR = 3 -LR = 0.2 Lateral Meniscus Sensitivity = 68% Specificity = 97% + predictability = 87% -predictability = 91% diagnostic accuracy = 90% +LR = 22 -LR = 0.3 The concensus between articles is that there is not one great clinical test for diagnosing meniscal tears. There are several very reliable tests. The reliability of the tests greatly depends on the skills of the person performing the test. Performing a battery of meniscal tests is the best way to rule in or out a tear. There are 5 clinical signs in the evaluation of a meniscus injury, joint line tenderness, pain on forced flexion, positive McMurray’s test, positive Apley’s grind and distraction test, and the presence of a block to extension. This is a good place to start, however each patient will be unique. Both Thessaly’s test and the joint line tenderness can greatly increase your ability in to correctly diagnose a meniscal injury. They are best when used along side other tests. It is also important that Thessaly’s test is performed correctly and that the patient reports the sensations they are experiencing correctly. With that test you rely on feedback from the patient, which can make it more subjective than the tests where you can feel the pop or click as a physician performing them. When Thessaly’s test and joint line tenderness are combined in an evaluation, the sensitivity increases to 93% for medial meniscus and 78% for lateral meniscus. The specificity also increases to 92% for medial meniscus and 99% for lateral meniscus. References Abel BE, Gibson TW, Harrison BK. The Thessaly test for detection of meniscal tears: validation of a new physical examination technique for primary care medicine. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19:9-12. Atay OA, Isbell WM, Johnson DL, Kocabey Y, Tetik O. The Value of clinical examination versus magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of meniscal tears and anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:696-700. Haddad FS, Sujith K, Rayan T. Do physical diagnostic tests accurately detect meniscal tears?. Knee surg sports traumatol arthrosc. 2009;17:806-811. Hantes M, Karantanas AH, Malizos KN, Theofilos K, Zachos V, Zibis AH. Diagnostic Accuracy of a New Clinical Test (the Thessaly Test) for early Detection of Meniscal Tears. J of Bone and Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:955-962. Learmonth, D. Aspects of the knee: meniscal injury and surgery. Trauma. 2000;2:223-230.