Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

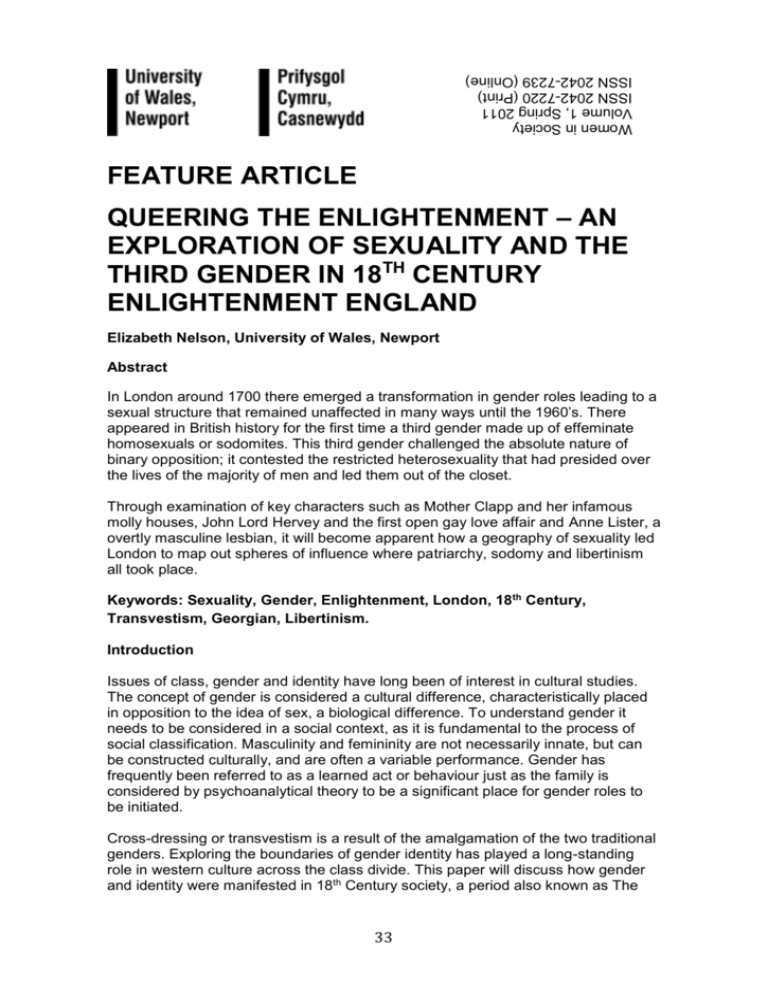

FEATURE ARTICLE

QUEERING THE ENLIGHTENMENT – AN

EXPLORATION OF SEXUALITY AND THE

THIRD GENDER IN 18TH CENTURY

ENLIGHTENMENT ENGLAND

Elizabeth Nelson, University of Wales, Newport

Abstract

In London around 1700 there emerged a transformation in gender roles leading to a

sexual structure that remained unaffected in many ways until the 1960’s. There

appeared in British history for the first time a third gender made up of effeminate

homosexuals or sodomites. This third gender challenged the absolute nature of

binary opposition; it contested the restricted heterosexuality that had presided over

the lives of the majority of men and led them out of the closet.

Through examination of key characters such as Mother Clapp and her infamous

molly houses, John Lord Hervey and the first open gay love affair and Anne Lister, a

overtly masculine lesbian, it will become apparent how a geography of sexuality led

London to map out spheres of influence where patriarchy, sodomy and libertinism

all took place.

Keywords: Sexuality, Gender, Enlightenment, London, 18th Century,

Transvestism, Georgian, Libertinism.

Introduction

Issues of class, gender and identity have long been of interest in cultural studies.

The concept of gender is considered a cultural difference, characteristically placed

in opposition to the idea of sex, a biological difference. To understand gender it

needs to be considered in a social context, as it is fundamental to the process of

social classification. Masculinity and femininity are not necessarily innate, but can

be constructed culturally, and are often a variable performance. Gender has

frequently been referred to as a learned act or behaviour just as the family is

considered by psychoanalytical theory to be a significant place for gender roles to

be initiated.

Cross-dressing or transvestism is a result of the amalgamation of the two traditional

genders. Exploring the boundaries of gender identity has played a long-standing

role in western culture across the class divide. This paper will discuss how gender

and identity were manifested in 18th Century society, a period also known as The

33

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

Enlightenment. The Enlightenment is often viewed as an anomaly in history, a

transitory moment when a number of philosophers and free thinkers supposed that

the perfect utopian society could be built on intellect and tolerance. However this

promptly crumbled amid the horror of the French Revolution in the late 18th Century.

In London around 1700 there emerged a transformation in gender roles leading to a

sexual structure that remained unaffected in many ways until the 1960’s. There

appeared in British history for the first time a third gender made up of effeminate

homosexuals or sodomites. This third gender challenged the absolute nature of

binary opposition; it contested the restricted heterosexuality that had presided over

the lives of the majority of men and led them out of the closet.

This paper seeks to demonstrate the nature of this sexual revolution. It will include

an introduction into homosexuality and cross-dressing in the 18th century and

observations on the vast differences in the class and gender divide. Key characters

such as Mother Clapp and her infamous molly houses, John Lord Hervey and the

first open gay love affair and Anne Lister, an overtly masculine lesbian will be

observed. Through this, it will become apparent how a geography of sexuality led

London to map out spheres of influence where patriarchy, sodomy and libertinism

all took place.

Sexuality in the 18th Century

Sex was easily accessible to men in London but the spread of sexually transmitted

disease and libertine values fashioned by prostitution were at odds, by the middle of

the century, with ideas of family love and puritan groups such as The Society for the

Reformation of Manners. Women, however, did not have strictly designated

heterosexual identities; a lesbian movement appeared in the 1770s and was mostly

ignored by society. Anne Lister (1791) was one of the first recorded stereotypically

masculine lesbians; women up until then had indulged in sexual passion with their

own kind through social friendships, but had always remained feminine in their

appearance (Whitbread, 1992). Unravelling the ceremony of transvestism within the

homosexual minority should go some way to explaining its position within 18 th

Century society.

For a brief moment during the 18th Century a flamboyant gay scene blossomed in

London. Queen Anne enjoyed dressing up in men’s clothes and was rumoured to

have been a closet queer herself; politics was awash with flamboyantly feminine

gents and working class men could be found in rooms above public houses giving

birth to bizarre and unfortunate objects. Debauchery was rife among the Georgians

(Trumbach, 1998).

From around 1700 there emerged a marginal society of adult males who focussed

their sexual desires solely towards other adult males and pubescent males. Men

such as these were instantly identifiable to their contemporaries by their speech,

mincing gait and natty attire – all of which were effeminate. Despite this, rather than

transforming themselves completely into women, they had combined particular

characteristics of men and women into a third gender. There was also an equivalent

minority of mannish women who solely desired other females, but they did not

34

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

appear until the 1770’s. Trumbach (1998) thus argues that “…it is therefore the

case that for most of the 18th Century there existed in Northern Europe what might

be described as a system of three genders composed of men, women and

sodomites.”

In the 18th Century this recognition and reorganisation of sexual conduct led, in the

later part of the 19th Century, to the use of the terms homosexual and heterosexual.

These terms were then used to describe a heterosexual majority and a homosexual

minority in sexual behaviour. Before 1700 in European society homosexual

behaviour was structured by age or gender. In Ancient Greece and Renaissance

Italy differences in age structured sexual behaviour; mature men enjoyed sex with

both women and sexually passive young men. In places such as South Asia

traditionally men of all ages would partake in relations with both women and passive

adult males. There was a socialisation of a third gender, the amalgamation of male

and female characteristics had found a dedicated place within society. It is thought

probable that within European society before 1700 the majority of men had feelings

for men and women. These desires were expressed through sex with females and

pubescent males. This model of behaviour had appeared throughout history, from

ancient Greece and Rome right through the Middle Ages (Herdt, 1991).

Rocke’s (1996) research on Renaissance Florence shows that by the age of thirty,

half of Florentine men had been involved in sodomy and by forty years of age, two

thirds had participated in it. Sodomy was therefore a common sexual stance. Age

structured the behavioural patterns of these men; boys were passive from fifteen to

nineteen, between nineteen and twenty-three was an intermediary phase where

they could be passive or active, but with the older man always being active and

after twenty three the men were always active. Most young men also used female

prostitutes up until they married at about thirty years old. Although penetrative sex

with men was against the law and outlawed by the church as immoral, this did not

stop the majority of upper class men, they just kept it well hidden. It was not until the

Restoration period that the brazenness of Lord Rochester was thrust upon

aristocratic society. The notoriously depraved Earl of Rochester wrote the play

Sodom; or the Quintessence of Debauchery in 1684, in which he described sodomy

with boys and women as apathetically depraved and exhilarating: “What tho the

letchery be dry, 'tis smart; A Turkish arse I love with all my heart” (Norton, 2007).

Although Rochester was married, with his wife and children living in Oxfordshire, he

claimed that the devil possessed him once he arrived in London and libertine

traditions became his philosophy. He would sleep with anything - girl, boy, (it is

even rumoured) animal. Yet Rochester and his aristocratic kind moved in an elite

world of proactive bi-sexuality; it was neither flagrant, made public nor condemned

by society. It was the height of hypocrisy.

Mother Clapp

In July 1726 a middle-aged woman with the moniker Mother Clapp was pilloried at

Smithfield’s market; a vociferous mob pelted her with rotten fruit and vegetables,

faeces, mud, decaying offal and dead animals. Did her punishment fit her crime?

She ran one of the most infamous gay bars in London town. According to Norton

35

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

(2005) she was the earliest recorded example in history of a Fag Hag. Margaret

(Mother) Clapp ran a drinking establishment in Holborn. It is difficult to imagine for a

moment that she was a maternal figure; she was more of a cackling old hag. It is

reported that the men would talk all manner of sickening and gross obscenity in her

hearing and she would be delightfully pleased with it. But her public house was not

just a drinking den; a police informant Samuel Stevens reported a visit he had made

on 14th November 1725 :

I found between 40 and 50 men making love to one another, as they call’d

it. Sometimes they would sit on one another’s laps, kissing in a lewd

manner, and using their hands indecently. Then they would get up, dance

and make curtsies, and mimick the voices of women. O, Fie, Sir! – Pray,

Sir. – Dear Sir. Lord, how can you serve me so? – I swear I’ll cry out. –

You’re a wicked Devil. – And you’re a bold Face. – Eh ye little dear Toad!

Come, buss! – Then they’d hug, and play, and toy, and go out by couples

into another room on the same floor, to be marry’d, as they call’d it. (Norton,

2005)

The police mole claimed to have been disgusted, but he managed to describe in

lurid detail to his senior officers what he had seen. It is mostly because of police

evidence such as this that anything at all is known about 18th Century London’s

escalating gay community.

The public house was just a front; Mother Clapp’s was a ‘molly house’, and her

clientele were known as ‘mollies’. The mollies gave themselves nicknames so as to

mask their true identity; these included Miss Sweet Lips, Plump Nelly, Lady Godiva

and The Princess Seraphina, who was also one of the first recorded drag queens.

This practise also takes place in contemporary society with transvestites and drag

queens giving themselves a stage or character name. According to the historian

Amanda Vickery ‘Molly culture had some similarities with the whole world of drag;

actually I think what it reminds me more of is ‘camp’ really. High octane, theatrical, it

can be sort of selfmocking, but at the same time can be life affirming’ (Marshall,

2003).

The mollies were almost all working or artisan class. They were butchers, bakers,

footmen or waiters, candlestick makers; in other words what would have been

thought of as respectable working class professions. However, what went on in

Mother Clapp’s back room was not considered respectable; it was undeniably a

disorderly house. The back room was called the Chapel or the Marrying Room. The

men would be christened with a woman’s name and a glass of gin would be thrown

into their face at the same time. This was almost certainly designed to mimic how a

baby is anointed during a traditional christening. The men would then come out and

describe to the rest of the mollies what they had been up to. This would include

graphic details of the sexual acts that had taken place, how the other person had

performed and sometimes even their ‘members’ measurements (Vickery, 1998).

Here was the emergence of the modern day homosexual man, gaily skipping into

cultural history. There had been homosexual activity prior to the 18 th Century and

36

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

some sodomites would probably have been effeminate, but this was not primarily

the case. From the 1660s to the 1730s the number of mollies began to increase and

these effeminate sodomites were becoming visible on the streets of London.

Passes were being made in pissing alleys, public latrines and even theatres,

London’s dark and shady show-grounds. But this behaviour was perilous. In 1533

Henry VIII had made sodomy (which referred to anal intercourse between men, or

sex between a man and animal) crime punishable by death and it remained so until

1861 when the sentence was reduced to 10 years in prison. This did not stop the

practice occurring, but sent it underground. Behaviour such as this would be

considered hazardous even in contemporary society; take the much-publicised case

of George Michael propositioning an off-duty police officer in public toilets in

America. He died a social death by bursting out of the closet in this manner.

Before the 1700s homosexuals were portrayed as predatory beasts stalking

effeminate young men; but at the turn of the century for the first recorded time in

British history, Georgian men felt entitled to a spot of inconspicuous sodomy on the

side. The early 18th Century saw men going to molly houses to dress up in women’s

clothes and meet like-minded gay men, here they pleasured each other and had

sex. This was something new. There was a geographical and a historical reason for

the emergence of the molly at this point in time. The frenzied chaotic capital offered

an array of unconventional identities. London became the centre of the molly culture

in Great Britain. In the 1720s there were 30 molly houses in London; it was not until

the 1960s that there would be more recorded homosexual social establishments in

the city (Trumbach, 1998). Georgian London was teeming with people, lots of whom

had left the countryside because the enclosure of common land meant that farming,

as a means of making a living, was no longer viable. This pattern of migration was

of great cultural importance. The rich and poor were thrown together in a city

surrounded by expanding trade and industry. London became very cosmopolitan

with recognisable minority communities settling in enclaves there. Identities were

lost in the big city, with people becoming confused by whom they were and by

whom they could be; this was not helped by the vast consumption of gin. Historian

Roy Porter (2000) wrote: “Beneath the powdered wig, emotional and psychological

disorder seethed. Beneath the surface of Britain’s cities was an underworld

populated by the poor, the desperate, the criminal and those who refused to

conform.” This is confirmed by Ackroyd’s observation that “the condition of London

itself encourages a life or sense of life, in which contraries meet” (2002).

Life was cruel for London’s unfortunate poor and gin was one of the ways of

numbing the pain. The streets were filthy and only the olfactorily deficient were not

affected by the stench. It has been reported that in 1730 more than 6.6 million

gallons of legally sold gin were consumed; this did not include the illegal liquor sold

from wheelbarrows in the street (Ackroyd, 2002). However, social dislocation

brought new ways of enjoying life, which is where Mother Clapp came in. She did

not just run a brothel, something more peculiar went on upstairs. It has been well

established through court testimony that one man would dress up as a bathycolpian

woman and pretend to give birth. Another man would play the role of the midwife

and would deliver a baby that was usually a doll or sometimes something more

absurd such as a pair of bellows. This pseudo-baby would then be baptised by

37

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

another molly dressed up as a minister. The meaning of such rituals is still widely

debated. Norton describes the binary opposition of the ceremony: “What they’re

doing essentially is turning on its head the standards and assumptions of

heterosexual society, then consolidating a gay identity as being specifically opposed

to a heterosexual identity” (2005). Norton puts forward a valid point, but perhaps

they were not simply mocking heterosexual customs. This ritual does seems to be a

contemptuous performance of a process that excludes them but it also shows a

wistfulness and longing to be included in a culture that rejects them.

As the molly subculture became more visible, an ominous moral backlash was on

its way. They became social scapegoats for a group founded in 1691 called The

Society for the Reformation of Manners. The latter considered it their moral duty to

stop the sordid behaviour that went on in the streets of London. Historian Amanda

Vickery (1998) describes them as a manic version of the neighbourhood watch,

trying to ‘out’ homosexuals, entrapping and informing on them. It is as a result of

their rise, that the whole Molly culture was exposed. In 1725 the Society besieged

Mother Clapp’s. It appears they hired two young gay hustlers to entrap the mollies

into having sex with them. Then one Sunday night in 1726 the police stormed the

place arresting 40 men dressed up as women and Mother Clapp. Many were

subsequently released through lack of evidence, but two were imprisoned for two

years, two were put in the pillory and the three proved to have committed sodomy

were hanged. Mother Clapp was found guilty of keeping a disorderly house and

condemned to the pillory. She did not survive (Trumbach, 1998).

John Lord Hervey

As the mollies were flushed out of society and driven under ground, working class

homosexual behaviour faded away from chronological record. However, that did not

stop the upper classes carrying on exactly as they pleased. The aristocrats of the

18th Century had always allowed themselves more liberty than they bestowed on

the lower classes. The social elite had inherited libertinism, a hedonistic way of life

allowing them to partake in sexual encounters so long as they were discreet. As

Foucault points out: “underneath the libertine, the pervert” (Foucault, 1979). It was

into this society that John Lord Hervey was brought up. Lord Hervey was rich,

striking, noble and droll; the first recorded historical character to have stereotypical

homosexual attributes (Halsband, 1973). It seems he minced rather than walked

and was always fully made up. His speech was affected and bulimic with French

and Italian phrases; a contemporary caricature of a gay man. Lord Hervey was not

only a successful politician, he was a close friend of Queen Anne and spin-doctor to

Robert Warpole, Prime Minister at the time. He achieved this social standing in

spite of the fact that he was overtly homosexual. One of Hervey’s girlfriends, Lady

Mary Wortley-Montague determined that "the world, consists of men, women, and

Herveys" (Norton, 1998). This serves as an example of the emerging sense of a

third gender; an amusing analogy intuitively expressed by Lady Mary without her

realising its meaning.

Lord Hervey shamelessly flaunted his flamboyance at court. Like the Earl of

Rochester a generation before, he was married and he had eight children. He also

38

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

had a mistress and a male lover at the same time. It is difficult to picture the

notoriety of flaunting your bisexuality at that level in the House of Lords or House of

Commons today. Hervey did not see himself as different from society because of

his sexuality, although he did presume himself more intelligent, more humorous,

more attractive and more determined (Rousseau, 2002).

In 1726, as the mollies were busily being hounded by the neighbourhood watch,

Lord Hervey was getting fed up with his dazzling but shallow life at court. It was

then he met his nemesis; a heterosexual country boy called Stephen Fox. While

Hervey loved the politics and the pretentious intrigue of court life, Stephen Fox

represented the opposite of this, a safe haven, and he became Hervey’s tonic.

Hervey was soon incapable of disguising his feelings for Stephen Fox. In a letter to

Stephen Hervey wrote:

The favours I have received at Your Honour's Hands are of such a Nature

that tho' the impression might wear out of my Mind, yet they are written in

such lasting characters upon every Limb, that 'tis impossible for me to look

on a Leg or an Arm without having my Memory refresh'd (Norton, 1998).

Although they initially agreed to keep their relationship private, Hervey visibly

blushed when Stephen was around, making their involvement quite obvious.

The turning point of the relationship came when Hervey discarded his wife and

children in the country and embarked on the Grand Tour with Stephen Fox. Whilst

touring they shared a bedroom, which was perceived by others as the innocent

behaviour of a Lord and his man-servant; but for them it was the start of a full blown

love affair. On their return to London fifteen months later Lord Hervey and Stephen

Fox set up home together in Hervey’s Burlington Street mansion. Lady Hervey was

relegated to her in-laws house on her visits to town. This love affair appears to have

been the first fully acknowledged homosexual relationship of the time. However,

with the growing public mood of anxiety that had been inflamed by the lurid trials of

the lower class mollies, Hervey had overstepped the mark (Norton, 1998).

Alexander Pope a caustic satirical writer focussed on Harvey’s homosexuality as a

way of bringing him down. He named him ‘Lord Fanny’ and based his character

‘Sporus’ on Harvey (Hyde 1970). Pope tore apart Harvey’s reputation at court and

soon afterwards he fell from power. Harvey had refused to abide by the code of

public conduct that had allowed the Earl of Rochester to do as he pleased a

generation earlier. He was not just camply dressed and having a sexual relationship

with Stephen; he had fallen in love and it was the aspect of openly loving another

man that was troubling to people. Whilst many of the Georgian aristocracy were

having affairs and behaving licentiously they did so behind closed doors. Hervey’s

ruin came because he was so open about his relationship with Stephen (Murray

1950, Halsband, 1973).

It also appears that Hervey’s obsession with his flagging career was pushing

Stephen away. Stephen was growing up, he had been a very young man when he

met Hervey and as got older he no longer wanted to stand in Hervey's shadow.

Stephen was bored with the responsibility of the increasingly needy, embittered and

39

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

disillusioned political liability that Hervey had become; so he married. Hervey’s

insecurity and his desperate need to dominate the relationship helped Stephen Fox

fall in love with his wife. Their relationship followed the path of a tragic love story:

Hervey was torn apart by two urges, he wouldn’t give up Stephen for his political

career nor vice versa. In later life, Harvey came across as acidic, malicious, selfpitying and vain. His saving grace was that he had refused to hide in the closet

choosing instead to declare his love to the world. When he died in 1743 it would be

another two hundred and fifty years before there would be another openly

homosexual politician in Britain (Murray, 1950, Halsband, 1973).

As the ideas of enlightenment, liberty and individuality bridged the class boundaries

of Georgian society it appeared that every man, whatever his social standing, could

become whatever he wanted to be. Where women were concerned no one really

cared if they were in love with each other and men found it hard to imagine them

having sexual relations. The pornographic novel ‘Fanny Hill’ was published in 1749

and was a bestseller. It established a theme much in favour with pornographers

ever since; women making love to women - aimed solely at the heterosexual male

market. The story followed country girl Fanny Hill to London where she ended up in

a brothel. The brothel had to ensure that Fanny was mature enough for sex with

men so prostitute Phoebe ascertained this by making love to her. However, this

doesn’t turn Fanny into a lesbian, it just makes her ready for sex with men (Cleland,

2002)

In the 18th Century sex meant penetration. Most men could not conceive of sex

between two women because there was no penetration involved; therefore

according to the laws on sodomy it was not technically illegal. Aristocratic 18th

Century women married their social equal. Marriage was a union between two

families with dynasty and money coming before love and emotion. This meant that it

was usually an unsentimental affair, so it was not surprising that Georgian women

entered passionate relationships with each other. Men had no interest in the

emotional or intellectual side of women, so the women amused themselves. When it

occasionally spilt over into a physical manifestation it was thought amusing but it

was not a vice in the way that male homosexuality was.

Anne Lister

The attitude towards female sexual relationship described above may have

remained unaltered, but for the discovery in 1988 of an astonishing set of diaries.

The secret diaries of Yorkshire landowner Anne Lister were unearthed after over

100 years behind a bookcase at the Lister ancestral home; Shibden Hall, near

Halifax. Anne Lister’s sexually explicit accounts turned around the idea of purely

romantic friendship constituting Georgian saphist history. Anne Lister appears to

have had her way with many of the highly reputable women of her day. Born into a

gentile Yorkshire family in 1791 Anne Lister inherited Shibden Hall from her Uncle

and became financially independent. All of Anne’s childhood friends had married but

Anne knew that was not what she wanted. From a young age Anne was aware that

she only had feelings for women, that she was a saphist, and that was what God

had intended for her. Know locally as an eccentric figure, she considered herself to

40

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

be a masculine oddity; modern society may describe her as having been butch.

Anne Lister conformed to the manly lesbian stereotype; she wore masculine

clothes, smoked a pipe and went fishing, shooting and hare coursing. Anne

appeared to be a very successful seducer; she used her social status to impress

and deployed her knowledge of women against them. She made a conscious effort

not to appear overtly mannish, but tried to address the women in a soft and

chivalrous manner. She twirled her fob watch and flattered them into submission

(Vickery, 1998).

In 1832 Anne Lister met her soul mate. Neighbouring heiress Anne Walker was

young, attractive and unmarried; she was also in awe of the older Anne. This

relationship was not just another flirtation for Anne Lister, she was determined that it

was going to last. It is reported that on the 4th October 1832 the two had dinner;

Anne Walker wore an evening gown, an appreciated feminine touch, and this

culminated in Anne Lister making the diary entry below:

‘she sat on my knee and I did not spare kissing and pressing, she returning

it’…then…’finding no resistance and lamp being out, let my hand wander

lower down gently getting to her queer, still no resistance so I whispered

‘surely she should care for me some little’ the reply ‘yes’ (Marshall, 2003).

Her diaries exposed an aspect of female relationships never explored by Jane

Austen. Anne Lister did not want to settle for someone beneath her social status so

playing the role of a gentleman entailed seeking a match that combined romance

and practicality; later that year Anne Walker moved into Shibden Hall. Unlike Lord

Harvey and Stephen Fox’s coupling, people talked about the two Anne’s but were

easily persuaded to accept two gentrified landowners living under one roof. Mainly

because she was a woman, Anne Lister was getting away with what Lord Harvey

could not. Her sexual situation was also helped by geography; she was an heiress

but she lived in a solitary house on a hill in Yorkshire, rather than at the prominent

London address of Lord Harvey. Country folk would have had no experience of

homosexuality and therefore would have no reason to assume that the living

arrangements of the two women were anything other than innocent. Anne Lister’s

masculine attire was most probably put down to her having to run the family estate;

with no male family member or spouse available to manage the tenants, she would

have had to have spent time on the land. A passage from the diaries revealed that

the two Annes, in an attempt to conform to gender roles and societal norms,

engaged in an unorthodox wedding ceremony:

Miss Walker told me in the hut that if she said ‘yes’ again it should be

binding, it should be the same as a marriage and she would give me no

cause to be jealous, made no objection to declaring it on the bible and

taking the sacrament with me at Shibden (Marshall, 2003).

Anne Lister died 6 years after their ‘marriage’. The unfortunate Anne Walker didn’t

get to enjoy her inheritance for long; she was committed to a mental institution by

her calculating relatives who discovered the lesbian relationship and proclaimed her

to be mad (Vickery, 1998).

41

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

The Gender Closet

Gender can be considered a performance with no foundation in sexual preference

or identity. Female impersonation, beginning with the mollies of the 18 th Century,

has long had psychoanalytical links with femininity and the masquerade

(Ruitenbeek, 1966). Freud arguds that some reactions stem from the unconscious

and that the unconscious is created when drives and instincts are disciplined by

social rules or cultural values (Rose, 2001).

Psychoanalytical concepts can be used to examine the cross dressing practises

that took place in the 18th Century; in particular the role of the molly and masculine

saphist. Alongside other conventional binaries the theoretical aversion between a

heterosexual and a homosexual identity is based around sexual boundaries.

Crossing these boundaries has become thought of as a tactic for the subversion of

gender and identity. Transvestism is largely considered to be a sexual obsession;

and has often been the expression of social or political dissent. Ackroyd suggests

that:

It is a persistent and universal activity; it exists wherever sexual behaviour

itself exists, perhaps lying dormant in most human beings; and it is to be

found in most cultures and across many centuries. But it still remains

inexplicable: why is there this repeated need for inversion and disorder?

(Ackroyd, 1979)

If a transvestite wants to be identified as a woman and we take that woman to be

the mother figure then the wearing of women’s clothes helps to re-create the bond

with the mother enjoyed as a child. Dressing up reunites the transvestite with the

representation of his mother; some take things further and actually aspire to

‘maternal happiness’ (Hirschfield, 1979). This has led to certain transvestites posing

as pregnant women and although this theory does not come into play until the 20 th

Century, the 18th Century rituals of the mollies suggests that it has been in

existence for almost three hundred years. As explained earlier, the mollies actually

took the role-play a step further by simulating the birth of a baby. In a more literal

sense Mother Clapp, catalyst for the mollies behaviour, becomes the mother figure

in the scenario: the mollies incongruously trying to become female in her likeness.

Cross-dressing visualises masculinity and femininity in ways that empowers and

disempowers women. For Anne Lister in the 18th Century, dressing as a man was

mostly ignored by society. There is very little literature available discussing the topic

and this may be because male clothing has no erotic value and was not therefore

considered sexually threatening. Lesbian cross-dressing could be a way of

asserting power in a patriarchal society that limits the societal standing of women.

Freud stated that:

…little girls notice the penis of a brother or playmate, strikingly visible and

of large proportions, at once recognise it as the superior counterpart of their

own small and inconspicuous organ, and from that time fall a victim to envy

for that penis (Richardson, 1996).

42

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

It could be said that Anne Lister was suffering from penis envy. She dressed and

acted in a masculine fashion not to impersonate a man but to seize the power

associated with the phallus. Frank Caprio substantiates this with his claim that:

Many lesbian relationships between two women become the equivalent of a

husband-wife relationship. The mannish or overt lesbian likes to take on the role of

the ‘husband’ and generally attaches herself to the female partner who is feminine

in physique and personality. She regards the mate as her ‘wife’ (Caprio, 1954).

It is easy to imagine from the diaries that the relationship between Anne Lister and

Anne Walker was as such. Anne Lister describes herself in the husbandly role,

sitting reading a newspaper or catching up with estate business while Anne Walker

does some sewing or painting. It is a gendered view of an unorthodox marriage.

The emulating effect of transvestism has a communicative role to play; it is perhaps

an expression of the intention of its bearer to consciously undertake the role of

opposing gender.

Conclusion

When Anne Lister died in 1840, Queen Victoria was on the throne and the

hedonistic Georgian age was over: an age of experimentation, where England

appears to have let its hair down and felt the first awakenings of a conspicuously

gay culture. It was a tentative era, where ideas about what makes you who you are,

were more individual and adaptable than they can sometimes be today. It seems

that the upper classes and the aristocracy had always had the privacy and

autonomy to be sexually alternative in their choices, tolerating bisexuality.

The resettlement of so many poorer country folk to London, where their behaviour

was not scrutinised, observed or inhibited by their families and peers, enabled the

lower classes to experiment with their sexuality, thus identifying the importance of

geography in terms of sexuality. The press exposure of molly culture increased

homophobia, yet at the same time paradoxically publicised the gay community. If

you lived in Manchester in the 1720s and you harboured secret feelings for men you

might read the newspapers and as a result make your way to London. On the other

hand as the newspapers stories gathered momentum, there was an up-roar of

moral panic. People feared that given half the chance any man might engage in

sodomitical liaisons; falling foul of male lust. This encouraged the press to whip up

public fury. In May 1726 the London Journal demanded drastic action against any

molly caught:

Common Hangman tie him Hand and Foot before the Judge’s Face in open

Court, that a Skillful Surgeon be provided immediately to take out his

Testicles, and that then the Hangman sear up his Scrotum with an hot Iron

(Norton, 2005).

Sexual difference traverses an array of cultural and historical contexts. According to

Goffman gender refers to the culturally established correlates of sex (Ekins, 1996).

It can be determined by you or by others depending on social constraints, and is an

essential component in the presentation of yourself to the world. Sexual identity is

43

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

encoded by gender. The majority of us are either male or female, perhaps an

uncomplicated way to begin. Difficulties arise when we start to understand that male

and female mean different things to different people. How we live, observe, and

relate to our peers depends in part on how we empathise with each others’

masculinity or femininity. These meanings are subconsciously significant in

everybody’s lives; within society, politically and sexually. As connotations range

from the superficial to the extremely complex, issues of gender have always carried

great potential for disagreement.

The idea of a third gender seemed to emerge with Lady Mary Wortley-Montague’s

opinion of Lord Hervey in the 1730s as being neither definitively male nor female.

There have been cultures where transvestism has been institutionalised with the

cross-dresser given common standing as an honorary third gender. Perhaps then

clothing or dress becomes the agenda, expressing the underlying social structures

of class, gender and identity. Dress does have a communicative role to play yet it is

unstable and conflicting in its portrayal. The emulating effect of transvestism is an

expression of the intention of its bearer to consciously undertake the role of the

opposing gender. The Georgians undertook the view that whom you have sex with

defined you as a person, a viewpoint also held in contemporary society. It appears

however, that during the 18th Century people possessed a keen sense of having

multiple roles to play and did so mostly without remorse.

REFERENCES

Abelore, H., Barale, M.A and Halperin, D.M. (Eds) 1993. The Lesbian and Gay

Studies Reader. New York: Routledge.

Ackroyd, P. 2002. Albion – The Origins of the English Imagination. London: Chatto

& Windus.

Ackroyd, P. 1979. Dressing Up – Transvestism and Drag: The History of an

Obsession. London: Thames & Hudson.

Ackroyd, P. 2001, London - The Biography. London: Vintage.

Butler, J. 1999. Gender Trouble – Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New

York and London: Routledge.

Butler, J. 1991. Imitation and Gender Insubordination. In Fuss, D. Ed. Inside/Out –

Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories. New York: Routledge. pp 13-32.

Capiro, F. 1954. Female Homosexuality: A Psychodynamic Study of Lesbianism.

New York: Citadel Press.

Chadwick, W. 1996. Women Art & Society, 2nd edn. London: Thames & Hudson.

Cleland, J. 2003. (New edition) Fanny Hill: Or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure.

England: Wordsworth.

44

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

Creekmur, C. K. and Doty, A. Eds. 1995. Out in Culture – Gay, Lesbian, and Queer

Essays on Popular Culture. London: Cassell.

David, H. 1997. On Queer Street – A social History of British Homosexuality 18951995. London: Harper & Collins.

Doty, A. 1993. Making Things Perfectly Queer – Interpreting Mass Culture.

Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Edgar, A. Sedgwick, P. Eds. 1991. Key Concepts in Cultural Theory. London and

New York: Routledge.

Ekins, R. 1997. Male Femaling – A grounded Theory Approach to Cross Dressing

and Sex Changing. London and New York: Routledge.

Ekins, R. King, D. Eds. 1996. Blending Genders – Social Aspects of Cross-Dressing

and Sex-Changing. London and New York: Routledge.

Eldeman, L. 1991. Seeing Things: Representation, the Scene of Surveillance, and

the Spectacle of Gay Male Sex. In FUSS, D. Ed Inside/Out– Lesbian Theories, Gay

Theories. New York: Routledge, pp 71-93.

Foucault, M. 1979. The History of Sexuality – An Introduction. Great Britain: Allen

Lane.

Hallett, M. 1991. The Spectacle of Difference – Graphic Satire in the Age of

Hogarth. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Halsband, R. 1973. Lord Hervey: Eighteenth-Century courtier. Oxford: Clarendon

Press.

Horne, P. Lewis, R. (Eds.) 1996. Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual

Culture. New York: Routledge.

Hyde, M. H. 1970. The Other Love: An Historical and Contemporary Survey of

Homosexuality In Britain. London: Heinemann.

Kellwe, W. Holzworth, H.W. 1994. A Double Life. New York: Scalo Publishers.

Marshall, J. 2003. Queer as 18th Century Folk. [off-air video recording: DVD]

Channel 4. 9th Dec 2003.

Morton, D, Ed. 1997. A LesBiGay Cultural Studies Reader. London: Westview

Press.

Murray, J. Ed. 1950. Lord Hervey and His Friends 1726–38, ed. the Earl of

Ilchester. [online book] London.

45

Women in Society

Volume 1, Spring 2011

ISSN 2042-7220 (Print)

ISSN 2042-7239 (Online)

http://openlibrary.org/books/OL6087992M/Lord_Hervey_and_his_friends_1726-38

(2nd February 2011)

Norton, R. 1998 updated 2007. England's First Pornographer, A History of

Homoerotica. [online essay] http://rictornorton.co.uk/wilmot.htm (2nd February

2011)

Norton, R. 2005. Mother Clap's Molly House, The Gay Subculture in Georgian

England [online essay] http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/mother.htm (2nd February

2011)

Norton, R. Ed. 1998. Town and Country The Gay Love Letters of John, Lord Hervey

to Stephen Fox. Excerpts from My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the

Centurie. [online essay] http://rictornorton.co.uk/hervey1.htm (2nd February 2011)

Porter, R. 2000. (new edition) London: A Social History. Penguin.

Richardson, D. (Ed.) 1996. Theorising Heterosexuality – Telling it Straight.

Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Riviere, J. 1966. Womanliness as a masquerade. In, Ruitenbeek, H. M. (Ed.)

Psychoanalysis and Female Sexuality. New Haven: College and University Press,

pp 209-220.

Rose, G. 2001. Visual Methodologies – An Introduction to the interpretation of

Visual Methods. London: Sage.

Rousseau, G. S. 2004. English Literature: Restoration and Eighteenth Century. In

Summers, C.J. An Encyclopaedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender & Queer

Culture. [online book].

http://www.glbtq.com/literature/eng_lit4_restoration_18c.html (2nd February 2011)

Sedgwick, E. K. 1990. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley, Los Angeles:

University of California Press.

Smart, C. 1996. Collusion, Collaboration and Confessions. In Richardson, D. (Ed.)

Theorising Heterosexuality – Telling it Straight. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open

University Press.

Trumbach, R. 1998 Sex and the Gender Revolution Volume 1 – Heterosexuality

and the Third Gender in Enlightenment London. Chicago & London: The University

of Chicago Press.

Vickery, A. 2003 (new edition). The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in

Georgian England. Yale: Yale University Press.

Whitbread, H. Ed. 1992. I Know My Own Heart: The Diaries of Anne Lister, 17911840 (Cutting edge lesbian life & literature). New York: New York University Press.

46