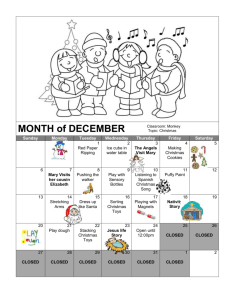

EPBC Nomination to list in the Endangered category: Christmas

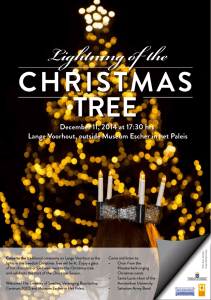

advertisement