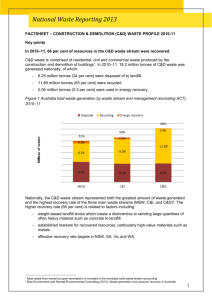

DOCX 105KB - Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

advertisement