Do EPA Regulations Disproportionately Affect

advertisement

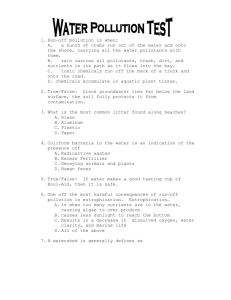

Paper currently being reviewed by the Center for Economic Studies – it will be uploaded as soon as it is cleared. Do Environmental Regulations Disproportionately Affect Small Business? Evidence from the Pollution Abatement Costs and Expenditures Survey Randy A. Becker, U.S. Census Bureau, CES Cynthia Morgan, U.S. EPA, NCEE Carl Pasurka Jr., U.S. EPA, NCEE Ronald J. Shadbegian, U.S. EPA, NCEE After the passage of the 1970 Clean Air Act Amendments and 1972 Clean Water Act Amendments, the United States realized significant improvements in both air and water quality. These improvements were due in large part to increasing stringency of environmental regulations that led to steady declines in emissions from industrial sources. According to the Pollution Abatement Costs and Expenditures (PACE) survey, the U.S. manufacturing sector spent nearly $21 billion dollars on pollution abatement operating costs (PAOC) to comply with environmental regulations in 2005. Policymakers have an ongoing interest in how these regulations affect the economy. There is a sizable literature on the effects of environmental regulations on plant-level productivity [Färe, Grosskopf and Pasurka Jr. (1986), Boyd and McClelland (1999), Berman and Bui (2001a), and Gray and Shadbegian (2002, 2003, 2006), Shadbegian and Gray (2005), investment [Gray and Shadbegian (1998)], and employment [Berman and Bui (2001b), Morgenstern, Pizer and Shih (2002), Greenstone (2002), and Cole and Elliott (2007)]. On whether the impact of environmental regulations differs by establishment size, Dean et al. (2000) find that industries with high pollution abatement costs had fewer small business formations. Meanwhile, Becker (2005) finds that air pollution abatement expenditures under the Clean Air Act were disproportionately higher for larger establishments sometimes, and sometimes the 1 reverse, depending on the air pollutant.1 In this paper, we consider all pollution abatement expenditures and the impact of all environmental regulations, and whether they differ by establishment size. We might expect differences in pollution abatement spending by establishment size because of statutory, enforcement, and/or compliance asymmetries (Dean et al. 2000; Becker 2005). Statutory asymmetries exist when regulations explicitly impose less stringent requirements on certain types of businesses. The Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) of 1980 imposes requirements on EPA (and other federal agencies) to thoroughly consider the economic impacts rules and regulations will have on small businesses. The objective is to ensure that small businesses have a voice in the process when EPA is making policy determinations in developing its rules and regulations. Furthermore, the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA) of 1996 enacted a range of provisions, including several amendments to the RFA. In brief, SBREFA requires EPA to solicit and consider flexible regulatory options that minimize adverse economic impacts on small entities. It also added a provision that allows small entities adversely affected by a final rule to challenge the agency's compliance with the RFA's requirements in court. Thus, we would expect to find that small businesses are not disproportionately affected by environmental regulations. Enforcement asymmetries result when regulators choose to target certain establishments over others, and this decision may hinge on establishment or firm size. Finally, compliance asymmetries arise when regulatory compliance involves significant fixed costs. For example, some pollution abatement is quite capital intensive, which would result in 1 Beyond these two publications, there is a series of non peer-reviewed studies, funded by the Small Business Administration (SBA), begun by Professors Thomas Hopkins and Mark Crain (with several co-authors) in the mid-1990s. 2 higher costs per unit of output for smaller establishments. Here, we consider the net effect of these three asymmetries. The latest report by Crain and Crain was released by the SBA in October 2010 (without the benefit of peer review). In this report, the authors use state by two-digit SIC industry level data from the 1992 Census of Manufacturers and the 1994 PACE Survey to examine whether or not small businesses had disproportionately higher pollution abatement costs, measured as total pollution abatement costs (PAOC plus pollution abatement capital expenditures). They find that pollution abatement costs are disproportionately higher for small businesses. However, these data are not appropriate to analyze this question for a number of reasons. The main reason is that the data do not contain any information on establishment size (obviously, a very important variable in an analysis of this type) since all the data is at the industry level. Nevertheless, in order to get a better understanding of their methodology, we (attempt to) replicate the report’s results using the industry data. While we can qualitatively replicate their results, we cannot obtain their exact estimates.2 We find that their key result - small businesses are disproportionately impacted by environmental regulations - is quite sensitive to their choice of specification. We further explore the issue of environmental regulations and establishment size using more 2 We contacted Professor Mark Crain and the SBA to ask them for the underlying data for this study. Because they were unwilling to share their data with us, we reconstructed their data set on our own. One reason why we could not exactly replicate their results is that in 1992 CM and 1994 PACE survey there were 309 state by two digit SIC industries for which all required data was necessary, but Crain and Crain only used 208 state by two digit SIC industries in their analysis. We do not know why they only used 208, but we do not believe this affects their results. 3 appropriate data. In particular, we employ the U.S. Census Bureau’s establishment-level data from the PACE surveys of 1979-1982, 1984-1986, and 1988-1994. To this, we merge data on these establishments from the Annual Survey of Manufactures (ASM) and CM, including employment, value of shipments, four-digit SIC industry, geography, and plant vintage (as measured by an establishment’s first appearance in the CM). We have over 200,000 establishment-years of observations for estimating the relation between establishment size and environmental expenditures. Here we focus on establishments’ PAOC intensity – that is, their pollution abatement operating costs per unit of economic activity. For the denominator we employ establishment employment or total value of shipments; we find that this choice makes little difference in our qualitative results. We model PAOC intensity as a function of 6 establishment size categories: 1-49, 50-99, 100-249, 250-499, 500-999, and 1000 or more employees. Additional controls include dummy variables for 4-digit SIC industry and year. Since the value of dependent variable is bounded from below for a significant number of observations, the model is estimated via a Tobit specification. Our preliminary results show that PAOC intensity increases monotonically with establishment size – a result that is robust to various changes in specification (e.g., the inclusion of controls for state and/or plant age). We also find that a simple regression of PAOC intensity (PAOC per employee) on establishment employment, controlling for 4-digit SIC industry, results in a significant positive coefficient on establishment size – again suggesting that larger establishments have higher environmental expenditures per unit of activity. References 4 Becker, Randy A. “Air Pollution Abatement Costs under the Clean Air Act: Evidence from the PACE Survey,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 50, 2005, 144-169. Berman, Eli, and Linda T. Bui, “Environmental Regulation and Labor Demand: Evidence from the South Coast Air Basin,” Journal of Public Economics, 79, 2001a, 265 – 295. Berman Eli and Linda Bui (2001b) “Environmental regulation and productivity: evidence from oil refineries.” Review of Economics and Statistics 83:498–510. Boyd GA, McClelland JD (1999) “The impact of environmental constraints on productivity improvement in integrated paper plants.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 38:121–142. Cole, Mathew and Rob J. Elliott. (2007) “Do Environmental Regulations Cost Jobs? An Industry-Level Analysis of the UK” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy vol 7. issue 1 (Topics) Crain, W. Mark and Nicole V. Crain.(2010). The impact of regulatory costs on small firms, Washington, DC: U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy. (http://www.sba.gov/advo/). Dean, T.J., R.L. Brown, and V. Stango, “Environmental Regulation as a Barrier to the Formation of Small Manufacturing Establishments: A Longitudinal Examination,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 40, 2000, 56-75. Färe, Rolf, Shawna Grosskopf and Carl Pasurka Jr. (1986) “Effects on Relative Efficiency in Electric Power Generation Due to Environmental Controls” Resources and Energy, Vol. 8, No. 2, (June 1986), 167-184. Gray, Wayne B. and Ronald J. Shadbegian. (2003) “Plant vintage, technology, and environmental regulation.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 46:384–402. Gray, Wayne B. and Ronald J. Shadbegian. (2002) “Pollution abatement costs, regulation, and plant-level productivity.” In: Gray WB (ed) Economic costs and consequences of environmental regulation. Ashgate Publishing. Gray, Wayne B. and Ronald J. Shadbegian. “Environmental Regulation, Investment Timing, and Technology Choice” Journal of Industrial Economics, 46, 1998, 235-56. Morgenstern, Richard D., “William A. Pizer, and Jhih-Shyang Shih, Jobs Versus the Environment: An Industry-Level Perspective” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 43, 2002, 412–436. Shadbegian, Ronald J. and Wayne B. Gray. “Pollution Abatement Expenditures and Plant-Level Productivity: A Production Function Approach” Ecological Economics, 54, 2005, 196-208. 5 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). 2006c. Revised Final Guidance for EPA Rulewriters: Regulatory Flexibility Act as amended by the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act. Available at: www.epa.gov/sbrefa/documents/rfafinalguidance06.pdf 6