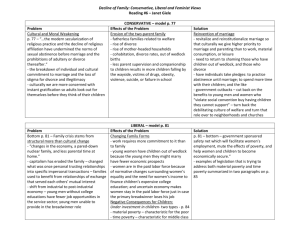

Chapter 6 Law and Relationships Marriage, while from its very

advertisement