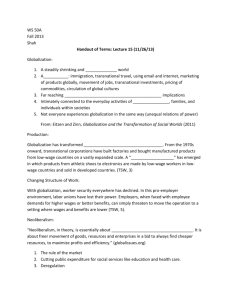

Neoliberalism K-HSS13 - Georgetown Debate Seminar 2013

advertisement