05_U1_L1 Composting

advertisement

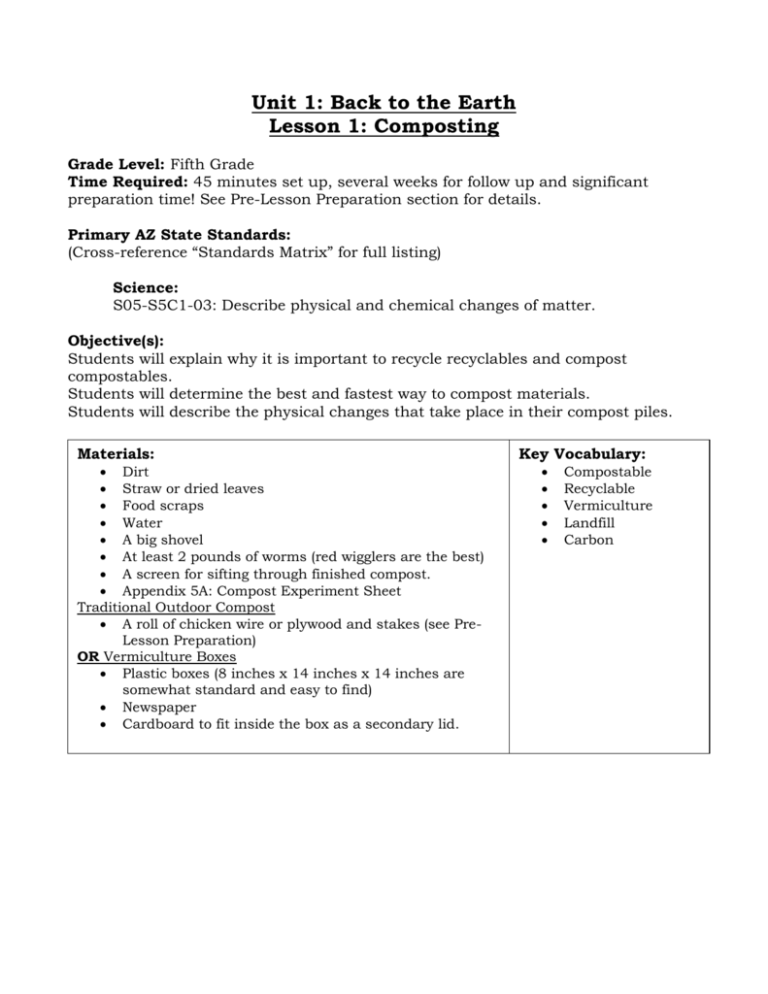

Unit 1: Back to the Earth Lesson 1: Composting Grade Level: Fifth Grade Time Required: 45 minutes set up, several weeks for follow up and significant preparation time! See Pre-Lesson Preparation section for details. Primary AZ State Standards: (Cross-reference “Standards Matrix” for full listing) Science: S05-S5C1-03: Describe physical and chemical changes of matter. Objective(s): Students will explain why it is important to recycle recyclables and compost compostables. Students will determine the best and fastest way to compost materials. Students will describe the physical changes that take place in their compost piles. Materials: Dirt Straw or dried leaves Food scraps Water A big shovel At least 2 pounds of worms (red wigglers are the best) A screen for sifting through finished compost. Appendix 5A: Compost Experiment Sheet Traditional Outdoor Compost A roll of chicken wire or plywood and stakes (see PreLesson Preparation) OR Vermiculture Boxes Plastic boxes (8 inches x 14 inches x 14 inches are somewhat standard and easy to find) Newspaper Cardboard to fit inside the box as a secondary lid. Key Vocabulary: Compostable Recyclable Vermiculture Landfill Carbon Preparation _X_ Adaptation of Content _X_ Links to Background _X_ Links to Past Learning _X_ Strategies Incorporated Instruction Features Scaffolding _X_ Modeling _X_ Guided Practice _X_ Independent Practice _X_ Comprehensible Input Grouping Options _X_ Whole Class _X_ Small Groups __ Partners __ Independent Integration of Process __ Reading _(X)_ Writing _X_ Speaking _X_ Listening Application _X_ Hands-on _X_ Meaningful _X_ Linked to Objectives _X_ Promotes Engagement Assessment __ Individual __ Group __ Written __ Oral Background Information: Composting is a great way to make the mental connection between waste and resources as well as life and death. So much of gardening and farming is focused on getting seeds to grow, watering plants, and supporting life. However, gardens and farms to replenish the soils with organic material through the process of decomposition. On many farms, old vegetation or cover crops are tilled under the soil and allowed to decompose before replanting the fields. Smaller scale gardeners, however, often have a compost bin that they maintain during part of the year, or perhaps the entire year through. In their compost bin, gardeners will add vegetable and food scraps from the kitchen or grass cuttings from the lawn, carbonaceous material such as dried leaves or straw, worms, and small quantities of dirt. Each of these ingredients is necessary to maintain a balanced and functional compost pile. The green materials are a food source for the worms and nitrogen for the other decomposers. The carbonaceous materials break down into organic material within the dirt. Lastly, the dirt itself provides needed grit for earthworm digestion and microbes for decomposition. In addition, compost piles need air, water, and heat to really get going. Water, heat, and air help the worms and promote quality conditions for decomposition. If you are composting in a dry climate, it is important to add water to the pile from time to time. The piles must be turned with a shovel on occasion to make sure the piles stay aerated and don’t become waterlogged, anaerobic, and smelly! Finally, while the decomposition process will create some heat, warmer outside temperatures will help accelerate the chemical and physical decomposition process. Compost is considered finished when there are no longer large, identifiable chunks of composting material in it and the end product looks like rich dirt (in fact, it will be mostly worm castings). Putting unfinished compost on gardens actually robs plants of nutrients and stresses the plants. Consequently, only finished compost should be used in the gardens by applying 1 -2 inches on the surface and then working it into deeper layers of your soil before planting. A popular form of urban composting is worm boxes, or vermiculture. A worm box can be neatly stored under the kitchen sink, requires less processing (turning, the piles and getting dirty), and produces smaller volumes of manageable compost than a traditional compost pile. However, worm boxes operate off the same principles and components as described for a traditional compost pile. To build a worm box, take a plastic tub, drill holes in the bottom and along the top sides for ventilation and drainage. Shred newspaper, moisten the paper (not soggy!) and lay down several inches of newspaper to create bedding. You can also ad dried leaves, since both newspaper and leaves are functioning as your carbonaceous material. Throw in some dirt and bury a few pieces of kitchen scraps (green material) to help the worms get started. Cut out a piece of cardboard and moisten it to create a well-fitted lid. From time to time, add and bury more kitchen scraps in different parts of the box as the worms eat it up. Just like a compost pile, monitor the balance to make sure things aren’t too dry or too wet and that the worms have enough to eat. In this lesson, teachers can opt to use either a traditional compost pile or a vermiculture box, depending on time of year, access to gardens, and availability of resources. Students will need time over the course of the next 4 weeks to follow up and maintain their experiments. Pre-lesson Preparation: At least a week before. 1. Gather materials needed for an outdoor compost pile or an indoor worm box. Especially important is collecting worms. You can either collect worms from outside by putting down wet cardboard on the yard overnight and seeing what worms migrate to it, or you can order worms online. 2. Talk to the cafeteria staff about collecting trash and food waste for one day. For traditional, outdoor, compost experiments: 3. Either set up some small, round enclosures (one for each group) with chicken wire to keep out critters (such as raccoons, squirrels, or mice), OR set up a more sturdy (and expensive) structure that can be partitioned for each group, particularly if the school will use it afterwards. To make a sturdier composting area, take sheets of plywood and create a box by using stakes to hold them upright and in place. Make sure one side is removable so students can access it. Areas can be partitioned with smaller pieces of plywood. For indoor vermiculture boxes: 4. Drill holes in the bottom and sides of boxes for ventilation before class. Activity Instructions: Sorting through trash Whole class 10 minutes 1. Drag over a full trashcan from the lunchroom to the front of the class. 2. Ask students, “What can you tell me about this trash?” Comments will vary. “Where do you think this trash goes?” To the landfill. “If I asked you to sort through this trash (which they are NOT going to do!), how much do you think would be recyclable? How much is food? How much is real trash?” Comments will vary. Encourage students to use percentages. 3. Tell students, “According to the US EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), 26% of our trash is compostable, and probably another 25% could easily be recycled or reused.” 4. Ask students to explain the words ‘compostable’ and ‘recyclable’. Compostable means it can be put into compost (organic trash pile) to be naturally decomposed back into dirt. Recyclable means that the materials can be processed again (at a recycling plant) and reused in some other form. 5. Ask students to explain why we should care about sorting our trash. Landfills are overflowing. Resources sent to landfills are not used again, they are buried or sent out to sea. Recyclable material could be used again, and compostable materials could be used to enrich the soils with needed organic material. Taking those items out of trash would also save on landfill space! Composting experiments Smaller groups of 3- 5 25 minutes 1. Tell students, “Today, I am NOT going to make you stick your hands into this smelly trashcan to sort the trash but we are going to experiment with ways that we can use the compostable materials for our gardens. Here are some scraps from today’s/yesterday’s lunch, and some other materials that you need to get started.” 2. Show students a sample of all the materials they will be using in their composting experiment. 3. Explain the role of each material (green materials, carbonaceous materials, dirt, and worms) as outline in the Background section. 4. Tell students, “Your job today is to create a composting guide for other students in the school that explains the best way to make compost. You will have to experiment with proportions and variables that may affect your compost.” 5. Ask students, “What environmental variables would affect decomposition?” Heat, water, air. Discuss information from Background with students. 6. Divide students into groups of 3-5. 7. Distribute Appendix 5A experiment sheets and have students fill out predictions. 8. Explain how to set up compost experiments. Traditional, outdoor compost 1. Inside each of the outdoor enclosures (either chicken wire or plywood), add dirt, green material, and carbonaceous material. (Students get to decide how they want to do this and how much of each material. They might also consider whether they want to shred things well, or leave bigger chunks.) 2. Water the pile well. 3. Add worms. 4. Have students document on their experiment sheets how they set up their pile. Vermiculture box 1. Shred newspaper, moisten and wring out excess water. 2. Put down a 3- 4 inches of newspaper 3. Add several hands full of dirt. 4. Add some food scraps by burying them under the newspaper. 5. Add ½ pound of worms. 6. Cut a big piece of cardboard to fit inside the box as a secondary lid. 7. Wet the cardboard well and insert. 8. Put the box in a cool, dark place with the lid of the box underneath to catch any moisture that drains from the holes. 9. Over the course of the next four weeks, have students record materials added (green, carbon, dirt, water), when they mixed the soil, and any other treatments they used. They will also record observations of how the materials are or are not breaking down and how much final compost was produced by sifting final dirt material through a screen. 10. Discuss results as a group. 11. In class extension As a final, concluding project, have each group of students make a brochure to distribute to the rest of the school promoting their compost recipe. Resources: Wastes, Resource Conservation, Reduce-Reuse-Recycle, Composting. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed on June 30, 2010 from http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/conserve/rrr/composting/index.htm Extensions: Willow Bend Environmental Center offers a 5th grade classroom program called “Trash and the Three Rs” where students learn how to reduce waste, reuse materials, and recycle in Flagstaff. Suggested fieldtrip “Recycling Tour” through Willow Bend.