Coherence Analysis - Boise State University

advertisement

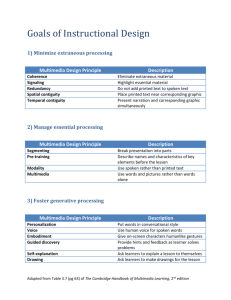

The Coherence Principle The basic idea of the coherence principle is to avoid any extraneous audio, graphics, or words. Research has shown in all three cases, learning is hampered when extra material is added that is not relevant to the course (Clark & Mayer, 2008). The coherence principle champions the idea that only material directly related to the main learning objectives be included. Anything extra, be it additional facts, “fyi” type quotes, sound effects, or background music, simply take up valuable space in the highly limited working memory, according to the cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Personally, I have seen this principle at work many times. One particular set of presentations was when I worked at a Fortune 500 company. The first day was nothing but sitting in front of a computer watching training presentations. To be frank, they were incredibly boring. It was simply narration, a picture, and the highlights of the narration. There was no background music, sound effects, or non-pertinent information. At the end of the presentations, there were tests that had to be passed before moving on. On every test (at least 10), I passed the first time I took it. I had no prior information about the company or the material being studied. Frankly, I was surprised I did pass all of them because of how simple (aka boring) they were. At the time, I just thought the company had been cheap and not spent much time on the training material. I am coming to learn they did just the opposite. Another example includes the use of PowerPoint. In this case, the criteria of the coherence principle were violated. Every year, each of the high schools in my district have a freshman orientation to introduce incoming freshmen to the school as well as the requirements set forth by the state. The district had one of the schools design the program. There is quite a bit of information, so the working memory of these new students and parents would be getting a workout just based on the sheer amount of information. The presentation was done on PowerPoint but turned into a video; therefore, the parents and students watching the presentation had no control over the speed. The video was narrated verbatim from the words on the screen. Additionally, there was background audio, which itself sometimes masked the voice of the narrator. According to Clark and Mayer, “background music and sounds may overload working memory, so they are most dangerous in situations in which the learner may experience heavy cognitive load, for example. When the material is unfamiliar, when the material is presented at a rapid rate, or when the rate of presentation is not under learner control.” Clearly, this violates the extraneous audio portion of the coherence principle. The presentation was also presented with extraneous graphics. Many of the slides included pictures of items that, while academic, did not relate to what was being talked about. For example, when reviewing the credits needed to graduate, in addition to a mortar board (which might be considered okay), there were pictures of students with arms around each other, students carrying books, and students cheering at a sporting event. These extra pictures interfere with the learners ability to makes sense of the presented material (Clark & Mayer, 2008). The coherence principle seems to be consistent with the other and works well with the other principles we have studied thus far. The modality principle, which states that words should be presented as audio narration rather than text on the screen, is in line with the coherence principle. The modality principle seeks to reduce the cognitive load on the visual channel and distribute the information more evenly so new learning can occur. Its elimination of the on screen text reduces the cognitive load on the visual channel. Similarly, the redundancy principle, seeks to reduce the cognitive load on any one channel. In this principle, the designer of the material should explain visuals using narration or text. Once again, this is consistent with the coherence principle. Removing the text eases the load on the visual channel. Conversely, removing the audio eases the load on the auditory channel. The multimedia principle teaches us that words and graphics are more effective than words alone (Clark & Mayer, 2008). The important part we need to remember when comparing this principle to the coherence principle is the idea of extraneous graphics. All graphics need to directly relate to the new material to be learned. Any graphic not directly related needs to be eliminated for the most new learning to occur. According to Mayer (1999), learning occurs with the learner engages in three cognitive processes. First, selecting the important words from a section. Second, being able to organize those words into a verbal model. And finally, organizing the images. This fits very well into the coherence principle. If a passage is being narrated and shown on screen, the learner may have trouble picking out the key words. Additionally, he may turn his or her attention to a visual that has nothing to do with the presented material, or reading text associated with that visual. Using the coherence principle to eliminate the material not needed will help the learner achieve the cognitive processes listed. This theory was interesting to me. I understand the idea and it is always hard to argue with hard evidence. I have always been a student that listens to music while doing my work. The research shows that, while my work is not degraded, it is done slower. From a designer standpoint, I like this theory. More time can be dedicated to the core material and less time coming up with sound effects, background music, extraneous graphics, etc. I just have a few questions that I did not feel were answered. Moreno & Meyer indicated that eight studies had been done regarding the coherence principle, but did not disclose what subjects and grade levels. Would these results replicate themselves in other subjects? Would these results replicate themselves for students who do well in a particular subject? Does age and/or grade level matter? In the example studies, would the results have been different if we knew which students enjoyed the subjects? I would like to see more detailed research. I know many of the textbooks we use in traditional classes have a lot of extraneous information (text and graphics). As a teacher, I use this information to get students interest. Does the online environment drastically change the idea of extraneous information? I am definitely in no position to argue the results in an online environment, but my brief time teaching has shown me that sometimes, the extraneous information is what grabs a student’s attention. Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2008). E-learning and the science of instruction, 2nd edition. Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA. Mayer, R. E. (1999). Multimedia aids to problem-solving transfer. International Journal of Educational Research, 31(7), 611-623. Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. E. (2000). A learner-centered approach to multimedia explanations: Deriving instructional design principles from cognitive theory. Interactive Multimedia Electronic Journal of Computer-Enhanced Learning, 2(2), 2004-07. Retrieved March 1, 2009 from http://imej.wfu.edu/articles/2000/2/05/index.asp