Appendix A. List of Meetings - Documents & Reports

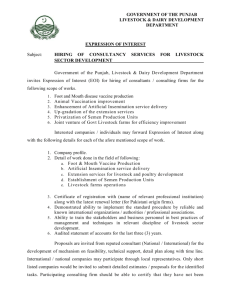

advertisement