Concepts, Essential Questions, & Inquiry

advertisement

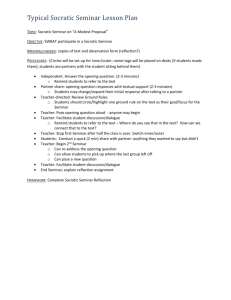

CONCEPTS, ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS & INQUIRY: What Would Socrates Do? Presented by RICHARD D. COURTRIGHT, PH.D. GIFTED EDUCATION RESEARCH SPECIALIST, DUKE UNIVERSITY TALENT IDENTIFICATION PROGRAM What is not covered by the Standards? • The Standards define what all students are expected to know and be able to do, not how teachers should teach… they do not—indeed, cannot—enumerate all or even most of the content that students should learn. • While the Standards focus on what is most essential, they do not describe all that can or should be taught. • The Standards do not define the nature of advanced work for students who meet the Standards prior to the end of high school. For those students, advanced work in such areas as literature, composition, language, and journalism should be available. What is not covered by the Standards? • The Standards set grade-specific standards but do not define the intervention methods or materials necessary to support students who are well below or well above grade-level expectations. No set of grade-specific standards can fully reflect the great variety in abilities, needs, learning rates, and achievement levels of students in any given classroom. “Teachers no longer are the sole keepers of knowledge to impart to their students…Children today can find information on any subject within seconds via the Internet. A teacher's job now is to teach students how to find primary sources, critically analyze the vast amounts of information out there and then apply their new learning to useful, real-world problems.” – Robin Hopper, assistant superintendent, Livingston Union School District, California Themes, or Essential Understandings of 21st Century Learning • • • Just-in-time content instead of just-in-case content Big problems need conceptual thinkers What problem must we solve today? • …poses the problem, dilemma, or creative project FIRST. • …BEFORE the mastery of facts begins. The New Paradigm • • • • Every day, teachers coaching students in skill practice, in answer to a driving question… What will your students question today? Discuss? Research? Debate? Create? Gifted Kids Can Handle “the Big Ideas”… Can be coached to ask the tough questions • • • …to tackle the big problems …to find the cures …to see the hidden themes A Metaphor…for the Paradigm Shift Toward Big Thinking • • Nuts and bolts teaching…teaching lots of individual “stuff,” just rattling around! …versus… Toolkit teaching…teaching thinking skills as tools to manage facts while approaching complex problems Four Core Elements of Lesson Design That Require a Lot of Thought • • • • Content objectives (what will they know?) Skill objectives (what will they be able to do?) Essential Understandings (what will they understand?) Essential Questions (what [problems] will they investigate or explore?) ….organized by an overarching concept • • • • Concepts Organize Our Lives. They make the content objectives—all the bits and bytes of data—matter. They prompt us to ask the Big Questions of Life. They make us use critical thinking skills to solve the Big Questions of Life. “The concepts fundamental to the human condition [family, authority, faith, love, change, causality, truth, and wisdom] are also fundamental to human learning—to our understanding of the world around us and within us. Consequently, such ideas can and should be fundamental to the educational process.” – Joyce Van Tassel-Baska and Catherine A. Little, Content-Based Curriculum for High-Ability Learners Concepts: Put Them into Action, Daily Individuality Society Legality/Illegality Access Force Freedom Order Structure Good/Evil Communication Systems Conflict Patterns Change Power Origins • • • • • Theme – an abstract concept that is transdisciplinary and elemental. Concept – an abstract, general idea of a thing or a class of things; a category or classification within a discipline. Generalization – a fundamental truth about the relationship between/among two or more interdisciplinary concepts. Principle – a fundamental truth, law or doctrine that explains the relationship between two or more concepts within a discipline. Fact – a specific detail, a bit of information that is verifiable. Which concepts are you passionate about? Which concepts matter to your students? • Relevance • Connection • Meaning • Learners do not get excited about facts -• Students get excited and passionate about ideas. Concepts: Abstract, Big, Open! • • • • • • • • Concepts are usually one word: abstract, infinite, and vague. Concepts inspire questions. Concepts require analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Concepts lead to generalizations, themes, and the art of argumentation. Concepts require higher levels of thought to absorb, understand, and explore. Concept learning is fundamental to knowledge acquisition. (Concepts improve memory and recall by organizing raindrop facts into rain barrels.) Concepts link disciplines together. (Remember how real-world problems are interdisciplinary? What interdisciplinary problem will drive your class?) Concepts link learners to the content. Essential Questions • • • inquire about key problems, issues, themes, concerns, or interests relevant to our students and our community are open-ended—why, how, what if, what questions Socratic, non-judgmental, neutral, inviting exploration of ideas • • • • • • …spark discussion …ask for interpretations, claims, argument …require evidence gathering …lead to Essential Understandings (thesis of the moment) …lead to products and performances Emphasize the production of solutions to real world problems in the manner of the practicing expert/specialist. THREE TYPES OF TEACHING ADAPTED FROM THE PAIDEIA PROPOSAL COLUMN ONE COLUMN TWO COLUMN THREE Acquisition of organized knowledge Development of intellectual skills -skills of learning Enlarge the understanding of ideas and values by means of by means of by means of DIDACTIC TEACHING COACHING INSTRUCTION MAIEUTIC OR SOCRATIC EDUCATION through through through Lectures, Responses Textbooks and Other Aids Exercises and Supervised Practice Active Participation In three areas of subject matter: in the operations of in the discussion of Language, Literature, and the Fine Arts Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening Books (not textbooks), Literature, Essays, Fine Arts, Historical Documents Mathematics and Science Calculating, Observing, and Problem-Solving, Observing, Measuring, Estimating Proposing and Opposing Ideas History, Geography and Social Studies Exercising Critical Thinking Involvement in Artistic Activities Involving Cognition in Involving Cognition in Involving Cognition in Knowledge and Comprehension Application and Analysis Synthesis and Evaluation Learner: Receptive Teacher: Directive Learner and Teacher are Interactive Learner: Directive Teacher: Receptive • Seminar Defined "Questioning students about something they have read so as to help them improve their understanding of basic ideas and values...[Seminars] are conversations, conducted in an orderly manner by the teacher who acts as leader or moderator of the discussion." (Adler, 1984) Rules for Conducting a Socratic Seminar 1. Seat the students in a circle. 2. The seminar leader may only ask questions. 3. All students must have read the selection. 4. Answers given to the question(s) are related to the text under study; no outside source is cited. Guidelines for the Socratic Seminar Leader • Asks an opening question. • Asks for clarification and precision of the response. • Redirects the question until a clear answer is given. • Looks for connections of the response to larger issues. • Involves everyone (keeping a seating chart may help with this). • Uses wait time. • Is an active listener. • Objectively receives the participant's answer. • Does not insist on common agreement; seeks diverging opinions in the answers. • Determines the resolution of the question. Developing Good Questions for Socratic Seminars The questions prepared for discussion should be interpretive. Three types of questions: Fact Interpretation Evaluation There should be an element of doubt regarding the answer to the question. Should be answerable based on what the author has said in the text. Should deal with the important, crucial elements of the work. Should relate specifically to the work at hand, rather than a question that could be asked about any work. Clarity and simplicity of the questions is important. The KISS rule applies. Should be interesting to you as leader of the discussion. Content Analysis: Preparing the Questions for a Socratic Seminar Read the selection. Read the selection again, and Evaluate the students' readiness for the content. Consider community or school factors for connecting themes. Underline crucial words, examining their precise meaning. Identify pivotal sentences or paragraphs in which major points are raised, argued or discussed. Make a list of the important points, questions and issues. Devise a series of questions to be addressed. Order the questions Devise a diagram or chart to frame the issues or indicate opposing opinions. Examine time available and prioritize important points. Prepare five questions; plan to use three; begin with the best question. Structure: "Ideal" Characteristics of a Socratic Seminar Who: Any and all students of any age. What: Any work of human creativity. When: Once a week on Wednesday. Where: In a circle. How: Badly, then better. Why: To develop deeper understanding of the ideas, values, problems, issues and themes in the curriculum. Why: To regain a large measure of the pleasures of teaching and the teacher-learner interaction. Why: To increase student thinking and reasoning ability. Why: To increase student communication ability. Why: For the joy of it. CONTACT: Rick Courtright Gifted Education Research Specialist Duke University Talent Identification Program 300 Fuller Street P.O. Box 90780 Durham, NC 27701 (919) 668-9130 (Phone) (919) 668-9141 (Fax) RCourtright@tip.duke.edu www.tip.duke.edu