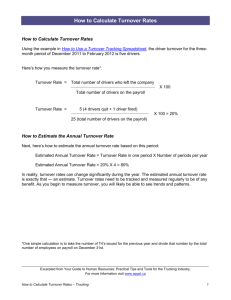

SHRM Foundation Grant Proposal Submission Checklist

advertisement