Houses, Hotels, and Hauntings: The Functions of

advertisement

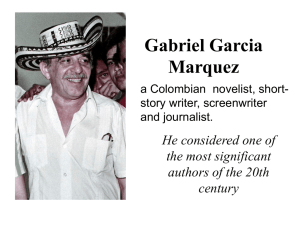

Dr. Rosenberg English 5321 Houses, Hotels, and Hauntings: The Functions of Physical Structures and Magical Realism in One Hundred Years of Solitude, Beloved, and The Lady Matador’s Hotel Magical Realist Houses & Hotels In magical realist texts, material objects reserve a special significance as compared to those found within other kinds of literature, especially realism. Though all fiction requires readers to visualize the material world represented on the page through words, magical realism requires that objects not only represent themselves “but also the potential of some kind of alternative reality, some kind of magic” (Zamora 30). The literal metaphor, a technique often used within magical realism, collapses the distance between the metaphorical and real. Zamora argues that magical realism is characterized by this quality of “semantic duplicity” (30) and that “magical-realists texts often conflate sight and insight…by making the visible world the very source of insight” (31). In these texts, physical dwellings often function as containers for both the magical objects and the narrative itself. They are also material sites of power contestations for the issues at play within magical realist texts. Houses and hotels are portals, liminal spaces between the real and the supernatural, which represent reality as portrayed by magical realism. Though the structures act as containers, they aren’t isolated from the world. Rather, they extend outward toward the communal and the cosmic, reimagining dominant discourses of gender, families, diaspora, the supernatural, and history. Gendered Spaces Houses are often depicted as gendered spaces—the dominion of female characters, especially matriarchs. Márquez positions Úrsula as the caretaker of the home while José Arcadio Buendía spends his time with scientific pursuits. The characters’ roles are representative of Faris’s observation that “the male tone within magical realism is often more visionary” while the female is “more curative” (Faris 186). Márquez depicts Úrsula, the traditional matriarch of the Buendía clan, as the tireless caretaker of the family’s house and a source of regenerative power against the effects of time on the household. He introduces her as an active, no nonsense “woman of unbreakable nerves” (Márquez 9) with a work ethic bordering on the marvelous. Throughout the novel, Úrsula’s concerns include cooking, sweeping, baking, arranging marriages, protecting the Buendía name, and raising children, even those who are illegitimate. She embraces her role as a stabilizing force for the family, outliving many of the novel’s younger characters. In a 1982 Playboy interview, Márquez claims that Úrsula “holds the world together” and describes her as “a prototype of that kind of practical, life-sustaining woman” (Dreifus 115). He argues that the virtue of womanhood lies in the fact that women “lack historical sense” (Dreifus 130). They are concerned with daily reality as opposed to politics or history. According to Márquez, the women “stay at home, run the house, bake animal candies—so that the men can go off and make wars” (130). Márquez situates women within the Buendía house, the center around which Macondo’s politics revolve. In direct contrast with Márquez’s view of women as ahistorical, Toni Morrison’s representation of women in Beloved situates the house as a physical embodiment of memory and its female inhabitants as the rememberers of history. Sethe, the matriarch of 124 Bluestone, can’t forget the horrors of slavery, which directly resulted in the infanticide of her daughter. Her daughter’s malevolent spirit has inhabited the house, filling the structure with “baby’s venom” (Morrison 1). The women and children are able to recognize the spirit and “put up with the spite in [their] own way” (Morrison 1), but the men flee from the house until Paul D arrives and expels the spirit from 124. In the first section of the novel, 124 functions as a bridge between the real and the supernatural. Faris links this function to the role of the female body in magical realist texts (Faris 181), establishing the connection between female characters, houses, and the supernatural. Beloved depicts the female body and the home as locations of trauma, which opens up the house as “an explicitly political space” that may become “a space of resistance” (Upstone 264). Rather than anchoring the narrative to a house, Cristina García’s The Lady Matador’s Hotel utilizes a hotel as a space of resistance connected to strong female figures that come into contact with the supernatural. The novel follows six main characters of varying ethnicities, genders, and nationalities that are all guests of the Hotel Miraflor over the course of a week, which happens to take place at the same time as an important political election. The novel’s second chapter focuses on Aurora, an ex-guerilla revolutionary, who works as a waitress at the hotel and lives alone because her family had been killed by the government during an unspecified civil war. When the military officials arrive at the Hotel Miraflor, the ghost of Aurora’s brother appears, asking her to avenge his death by killing a captain who is staying at the hotel. Thus, the Hotel Miraflor becomes a location where gender norms are challenged and the supernatural can be accessed. The novel’s characters are portrayed as gender fluid, which marks the hotel as an androgynous space. The female characters are all aggressive, sexual, and non-maternal. Suki Palacios, the lady matador, as nearly transcends gender with her sublime character though the crowds view her as a “scandalous woman playing at being a man” (García 4). She serves as the focal point of the hotel and whenever she appears at the hotel, the other guests note her presence. As an ex-guerrilla who has become part of the hotel staff, Aurora represents women who were displaced from their revolutionary roles during the civil war and reintegrated into the socio-political structure. Ironically, the novel’s least maternal character is a female adoption lawyer. Though she isn’t “maternally inclined” (García 14), Gertrudis Stüber uses the Miraflor as an adoption farm where prospective parents can pick up their children, which she’s bought from the pregnant mothers she houses at a location away from the hotel. In her business, both mothers and children become commodities to be sold under the guise of adoption, reflecting themes of diaspora and families discussed throughout the novel. Families, Lineage, & Diaspora In Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality In the Colonial Contest, Anne McClintock describes the emergence of what she calls “the paradox of the family,” which figures the family both as a metaphor that offers “a single genesis narrative for global history” and as an institution “void of history” (44). Thus, the family became both “the antithesis of history and history’s organizing figure” (44). One Hundred Years of Solitude and Beloved are concerned with issues of lineage—both genealogical and historical. The settlement of Macondo and the subsequent building of the house simultaneously mark the beginning of the Buendía line and the birth of a civilization. The Buendía family’s narrative represents the whole of Macondo and, some would argue, the experience of an entire continent. Beloved explores the connections between Sethe and her daughters as well as an entire lineage of people that begins with the Africans who died on the Middle Passage. Both novels demonstrate the paradox of the family in that the families are historical and ahistorical at the same time, allowing them to function as universal and political elements of the narrative. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, the Buendía house serves as the center of family life. Realizing that the house had filled with people and that her children “would be obliged to scatter for lack of space” (54), Úrsula enlarges the house. Throughout the novel, Úrsula attempts to bring characters back to the house when they’ve ventured too far from the center, usually because of a political endeavor. It is both the point of origin and the place where blood returns. Márquez uses a literal metaphor to describe the return of the child to the womb when José Arcadio dies and his blood travels back to the Buendía house: A trickle of blood came out under the door, crossed the living room, went out into the street continued on in a straight line across the uneven terraces…made a right angle at the Buendía house, went in under the closed door, crossed through the parlor, hugging the walls so as not to stain the rugs, went on to the other living room, made a wide curve to avoid the dining-room table…and went through the pantry and came out in the kitchen, where Úrsula was getting ready to crack thirtysix eggs to make bread. (Márquez 132) Tinged with humor, Márquez’s description of the blood returning to the house shows that, even after his death, José Arcadio’s blood makes sure not to “stain the rugs” or soil the dining-room table. Even the far-removed last remaining son of Colonel Aureliano Buendía dies on the doorstep of the house, demonstrating the importance of the home as a place that must finally be returned to. The events illustrate the significance of the matriarch as the figure that anchors the family and, by extension, the community. Úrsula doesn’t value full blood relatives over adopted family members or illegitimate children. There are various genealogical relationships present within the Buendía household, ranging from the fully adopted, such as Remedios Moscote, the daughter of Don Apolinar Moscote, to the far removed, such as Rebeca, the orphaned daughter of Úrsula’s second cousins. Úrsula feels responsible for taking them all into the home, contributing to her depiction as the mother of the world archetype and linking her with Eve, the first woman. Though Úrsula’s roles may be archetypal, her management of the Buendía household still remains a political act. In an interview with Rita Guibert, Márquez claims that the “power of women in the home…enables men to launch out into every sort of chimerical and strange adventure” (Guibert 40). He then claims that the civil wars that took place during 20th century Latin America wouldn’t have happened “if it weren’t for the women taking responsibility for the rearguard” (Guibert 41). The actions of the characters throughout the novel support Márquez’s observations. Most of the woman are located at the Buendía household and it’s the men that leave the home to work, organize strikes, travel, and fight wars. However, the political role of the home may become obscured because the establishment of the home has become associated with “the natural and timeless process of settlement” (McClintock 262). Through the process of settlement, the narrative links Úrsula and the other female characters with a cyclical conception of time that also obscures the political role of the home. Márquez explores the cyclical conception of time through Úrsula’s perspective, associating the female gender with timelessness and ahistoricity. Near the end of the novel, Úrsula repeats a conversation with her great-grandson José Arcadio Segundo that she’d had with Colonel Aureliano Buendía many years before. The repetition causes her to “shudder with the evidence that time was not passing, as she had just admitted, but that it was turning in a circle” (Márquez 335). The repetition of family names throughout the genealogical line over time reflects Úrsula’s conception of time as cyclical. Erickson argues that Úrsula’s view of time “encapsulates the novel’s reality, rather than just her subjective impression or a narrative technique of the author” (Erickson 144). Márquez revisits the returning to the origin motif a number of times throughout the novel, evoking a sense of historical determinism, which would seem to challenge the meaningfulness of political action. However, the Buendía house remains at the center of Macondo and is the location from which all politics emanate. The inextricable link between the family and the home highlights the dual roles of the José Arcadio Buendía and Úrsula as both the heads of the family and founders of the community. Their house, which “from the very first had been the best in the village” (Márquez 8), reflects their position at the top of Macondo’s social hierarchy. All of Macondo’s houses were “built in its image and likeness” (8), demonstrating that the larger community originates from and mirrors the Buendía family. The house also functions as a refuge from the outside world, exemplified by the male characters who strive for political success or territorial expansion but return to the Buendía mansion defeated. Ironically, it’s only through Macondo’s diaspora that the Buendía narrative and the town’s history are able to live on. Gabriel García Márquez, though not directly related to the Buendía family, is the only character that escapes Macondo’s destruction at the end of the novel. Though the Buendía genealogical line is wiped from the face of the earth, their stories and histories survive. The novel’s end proves Úrsula’s fear of incest to be legitimate. Amaranta Úrsula and Aureliano, unaware of their relationship to each other, fall in love and give birth to a child with “the tail of a pig” (412), realizing the family curse Úrsula feared at the beginning of the novel. The destruction of Macondo, the birth and death of the child as a product of an incestuous relationship, and the unlocking of the family’s history occur at the Buendía mansion simultaneously. The intrusion of modernity, as represented by the banana farmers, the gypsies, the corrupt government officials, and the soldiers, leads Macondo to its inevitable destruction. However, Gabriel García Márquez’s migration from the homeland enables Macondo to survive, highlighting the importance of diaspora within an increasingly postmodern world. Much like the Buendía mansion, Beloved’s 124 functions as a symbol of both separation from and yearning for community. According to Conner, the house “embodies the separation of the individual and the community” (Conner 65). Stamp Paid remembers that “nobody besides himself would enter 124” (Morrison 171) so the funeral for Baby Suggs had to be held in the yard. Insulted by their actions, Sethe refuses to attend the funeral, isolating herself even further from the community. As a form of self-protection, she hides herself inside 124, avoiding judgment. Because of Sethe’s actions, her daughter Denver acutely feels this sense of isolation. Morrison writes the same scene from Denver’s perspective. She states that her mother “wouldn’t let [her] go outside in the yard and eat with the others” and that staying inside “hurt” her (Morrison 209). 124 protects Denver from the community’s judgment but she remains severely cut off from everyone except for the house as haunted by the ghost of the infant, her mother, and later Beloved. The house acts both as “a respite and a jail” (Conner 54), which parallels the role of the community itself. After Sethe’s escape from Sweet Home, she develops a sense of personal identity through her interactions with the people of Cincinnati’s black community: Sethe had had twenty-eight days…of unslaved life. From the pure clear stream of spit that the little girl dribbled into her face to her oily blood was twenty-eight days. Days of healing, ease and real-talk. Days of company: knowing the names of forty, fifty other Negroes, their views, habits; where they had been and what done; of feeling their fun and sorrow along with her own, which made it better…All taught her how it felt to wake up at dawn and decide what to do with the day…. Bit by bit, at 124 and in the Clearing, along with the others, she had claimed herself. Freeing yourself was one thing; claiming ownership of that freed self was another. (Morrison 95) Morrison identifies the distinction between “freeing yourself” and “claiming ownership” of the self. By becoming part of the community, Sethe is able to begin to heal from the effects of slavery on her identity. Sethe’s growth and attachment to others during that time causes the community’s actions to be even more heartbreaking when it fails to warn her about the schoolteacher coming to 124. By not acting, the community implicates itself in Sethe’s murder of her infant daughter and it is only with the help of the community that Beloved and the horrors of slavery can be exorcised from 124. Sethe’s obsession with her family and isolation from the community keeps her from being able to move on from the past. Represented by her confinement to 124, she becomes trapped in a debilitating cycle of remembrance. Beloved, the embodied form of memory, begins to consume Sethe and “the bigger Beloved got, the smaller Sethe became” (Morrison 250). Though memory serves an important function, the past constantly reminds Sethe of the assault against her self worth during her time as a slave. Denver comes to this realization and decides that she must reach out to prevent Beloved from killing her mother: But there would never be an end to that, and seeing her mother diminished shamed and infuriated her. Yet she knew Sethe’s greatest fear was the same one Denver had in the beginning—that Beloved might leave…Leave before Sethe could make her realize that worse than that—far worse—was what Baby Suggs died of, what Ella knew, what Stamp saw and what made Paul D tremble. That anybody white could take your whole self for anything that came to mind. Not just work, kill, or maim you, but dirty you. Dirty you so bad you couldn’t like yourself anymore. Dirty you so bad you forgot who you were and couldn’t think it up. (Morrison 251) Sethe’s confinement to 124 and her all-consuming relationship with Beloved not only isolate her from the community, they cause her to forget who she is. She loses all sense of selfhood, giving her entire self to Beloved out of a sense of maternal love and guilt. Morrison depicts the loss of self as a result of slavery as worse than being killed or maimed. It is a total psychic erasure. Ultimately, Sethe’s focus on Beloved and therefore the past threatens to obliterate her. Family isn’t sufficient enough to save her. She must instead look outward toward the community. Like One Hundred Years of Solitude, the promise of surviving into the future relies on leaving the home. As guests of the Hotel Miraflor, all of the main characters of The Lady Matador’s Hotel are away from home, representative of an increasingly globalized and postmodern world. In Espacio, Cuerpo Y Masculindad Posmodernos En La Narrativa De Cristina García, Ignacio Rodeño argues that the fragmentation of the hotel’s space parallels the narrative structure of the novel (59). García marks each narrative shift with the location of where the section takes place within the hotel. It’s the physical space of the hotel that allows the characters and their personal histories to be interrelated against the backdrop of a political election. The hotel, a literal fragmentation of space, functions as a metaphor for the fragmentation of the characters’ identities. Each character comes from various countries and backgrounds. For example, Suki Palacios is a half-Japanese, half-Mexican lady matador from Los Angeles. Won Kim is a Korean textiles factory owner, but lives in an unnamed Central American country. Colonel Martin Abel represents the government while Aura Estrada is an ex-rebel now working as a waitress at the hotel. Because the novel’s setting is a major hotel for internationals, both intersections and conflicts between nationalities, ethnicities, gender, and politics take place. Though the hotel is depicted as a transitional space filled with people who are strangers to each other, the novel seems concerned with exploring the various forms families take. One of the novel’s major conflicts revolves around Gertrudis’s adoption business and its political problems. In this storyline, the hotel functions as a place where the children are commoditized and transformed into the diaspora of the unnamed country. After spending a few days at the hotel, parents of various nationalities leave with their adopted children back to their homes across the world. By the end of the novel, the government attempts to stop this practice, supposedly out of concern for “baby kidnappings and the exploitation of poor, child-bearing women” (163). At the end of the novel, the Cuban-American Ricardo does in fact kidnap his adopted child because he has already emotionally adopted her during his time at the Hotel Miraflor and finds his paternal bond to be too strong to let her go. Challenging traditional gender roles, García depicts the woman as non-maternal and the men as responsible caretakers. Not only does García use the hotel as a space for challenging gender roles, she challenges the distinction between life and death within families as well. The connection between Aura and Julio, the ghost of her dead brother, demonstrates that the hotel is a liminal space between life and death and the natural and supernatural. Politics and family business become entangled when the ghost of her brother asks Aura to avenge his death by using her wait staff position at the Miraflor to kill Colonel Abel. The ghost only appears on the hotel roof, which serves as a fitting location to connect the living and the dead. After asking Aura to kill the colonel, Julio tells her to “bring [him] hot chocolate” (García 51) instead of tea. Even the dead concern themselves with mundane matters—a representative element of the portrayal of ghosts within magical realism. The siblings still act as if both were alive, demonstrating that death doesn’t sever ties between family members, neither literal nor metaphorical. Faris argues that within many women’s magical realist narratives “the domestic sphere in magically real houses is usually not closed in on itself in isolation but opened outward into communal and cosmic life, as proven by the ghosts from other times and places that wander through them” (Faris 182). Acting as bridges between the individual and the communal and the natural and supernatural, these haunted houses function in ways unique to magical realism as a genre. Haunted Houses & Hotels Unlike the houses of Gothic texts, which isolate their magic and represent the ghosts as a supernatural occurrence, magical realist houses “instead provide focal points of [magic’s] dispersal” and “[welcome] cosmic forces, which may either terrorize before ultimately refreshing [the house], as in Beloved, or destroy it, as in One Hundred Years of Solitude” (Faris 182). The narrative implies that with the destruction of the Buendía house, the ghosts will also be obliterated. As Macondo and the Buendía family approach their ultimate ends, the accumulated ghosts still haunting the dilapidated mansion remind Aureliano Babilonia and Amaranta Úrsula of the weight of the past: Many times they were awakened by the traffic of the dead. They could hear Úrsula fighting against the laws of creation to maintain the line, and José Arcadio Buendía searching for the mythical truth of the great inventions, and Fernanda praying, and Colonel Aureliano Buendía stupefying himself with the deception of war and the little gold fishes, and then they learned that dominant obsession can prevail against death and they were happy again with the certainty that they would go on loving each other in their shape as apparitions long after another species of future animal would steal from the insects the paradise of misery that the insects were finally stealing from man. (Márquez 411) The dead continue to act the same as they had when living, revealing that “dominant obsession can prevail against death.” Erickson claims that the summary of the Buendías’ “useless repetitive” preoccupations illustrate how the ghosts haunt both the living and “haunt themselves by the repetition of their own past lives” (Erickson 142). The passage’s final image of the insects “stealing from man” foreshadows the end of the Buendía line. The characters’ belief in cyclical time and inability to change both keeps them figuratively alive after death and seals their final fate. Prudencio Aguilar’s haunting of José Arcadio Buendía is the catalyst for the creation of Macondo, a quasi-utopian experiment, and his ghost functions as a representation of the past in the present. Before he founds Macondo, José Arcadio Buendía kills Prudencio Aguilar for publicly suggesting José Arcadio Buendía’s sexual impotence. Prudencio’s ghost begins to haunt José Arcadio Buendía and Úrsula as “a traditional manifestation of guilt” (Erickson 151). José Arcadio Buendía remarks to his wife that the ghost’s reappearance “just means we can’t stand the weight of our conscience” and promises the ghost that “we’re going to leave this town, just as far away as we can go, and we’ll never come back” (Márquez 22-23). Thus the founding of Macondo occurs as the result of Prudencio’s haunting. However, Prudencio arrives in Macondo after searching for José Arcadio Buendía for many years, giving form to Macondo’s prehistory in the present (Erickson 151). At the beginning of the novel, José Arcadio Buendía concerns himself with technological progress and scientific knowledge but when Prudencio Aguilar’s ghost finds him, he “turns his back on progress and instead becomes obsessed with the seemingly eternal reiterations of time” (Erickson 151). Attempting to avoid the “second death” of not being remembered, Prudencio Aguilar meets with José Arcadio Buendía inside his laboratory, causing José to weep “for all those he could remember and who were now alone in death” (Márquez 77). When the time machine he’s attempting to invent breaks, José Arcadio Buendía becomes fully obsessed with the past: He spent six hours examining things, trying to find a difference from their appearance on the previous day in the hope of discovering in them some change that would reveal the passage of time. He spend the whole night in bed with his eyes open, calling to Prudencio Aguilar, to Melquiades, to all the dead, so that they would share his distress. But no one came…. Then he grabbed the bar from a door and with the savage violence of his uncommon strength he smashed to dust the equipment in the alchemy laboratory…. He was about to finish off the rest of the house when Aureliano asked the neighbors for help. Ten men were needed to get him down, fourteen to tie him up, twenty to drag him to the chestnut tree in the courtyard, where they left him tied up, barking in the strange language and giving off a green froth at the mouth. When Úrsula and Amaranta returned he was still tied to the trunk of the chestnut tree by his hands and feet, soaked with rain and in a state of total innocence. (Márquez 78) José Arcadio Buendía’s illness symbolizes the entrapment of the past he finds himself unable to escape. Erickson argues “the ghost actually signals the illusion of repetition” rather than “a simple indication of repetitions” (151). José Arcadio Buendía fails to understand this point and, as a result, he withers from existing in the present time into “a state of total innocence.” It is this obsession that eventually brings on Macondo’s destruction because the Buendía family can’t seem to adapt and function within an increasingly modernized world. Much like José Arcadio’s obsession, the ghost of 124 is a representation of the memories that enslave Sethe to the repetitive persistence of the past in Beloved. The haunting of the past is directly related to the house at the beginning of the novel since the ghost of the already-crawling? baby imbues 124 with its spirit. Morrison’s characterization of the house itself structures the sections of Beloved. The novel opens with “124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom” (1) and the last section begins with “124 was quiet” (239), paralleling the novel’s narrative arc. Erickson claims that the haunting of 124 isn’t simply metaphorical: The haunting of 124 is distinctly characterized as an augmentation of its material existence; returning to 124 at the end of the novel…. With the disappearance of the ghost, the house has been stripped off its additional spectral ‘load,’ reduced to the bare materiality of ‘just another weathered house needing repair.’ (Erickson 100) Denver even treats the house as if it were another character: “Shivering, Denver approached the house, regarding it, as she always did, as a person rather than a structure. A person that wept, sighed, trembled and fell into fits” (29). The volatility of the house affects all of its inhabitants but the characters who stay are the women, reversing the concept of home ownership as only being available to white men. However, Kawash claims that “the absence of men registers the wounds of slavery as much as it does the independence or strength of the women” (Kawash 73). Though Sethe owns 124 as a free, black woman, the house traps her because of its connection to the past. 124 acts as a bridge between Sethe and her deceased daughter, allowing her to stay connected to the daughter she loved so much she killed in order to keep her from experiencing life as a slave. However, the connection threatens Sethe from forming her own identity because the past constantly inhabits her present. The narrative of Beloved itself is composed of fragmented flashbacks, memories, and contemplation, disabling Sethe to act or escape the horrors of her past even though she’s now a physically free woman. Sethe’s understanding of memories as external “thought pictures” demonstrate that memories are as real as the material world (Erickson 102). The materiality of memory is illustrated through the process of the ghost of the already-crawling? baby moving from haunting the house to transforming into the character of Beloved. Kawash observes that as this process occurs, “the site of haunting shifts from the structure of the house to the agency of the ghost” (Kawash 72). Thus 124 need not be destroyed in order to loosen the hold of the past on Sethe though the ghost of Beloved must be either appeased or exorcised. When the community does exorcise Beloved at the end of the novel, Sethe continues to live at 124 and the house functions as a memorial to the past. Though Beloved disappears, the novel’s last few pages remind readers that the memory of slavery has not been fully exorcised, nor should it be. Brogan argues that the haunting of 124 by Beloved should be read “as emblematic of a nation’s haunting by its ugly racial history— a haunting that Morrison, in other contexts, calls ‘the ghost in the [national] machine’ or the racial ‘shadow’ that continues to darken American optimism” (Brogan 89). Sethe may be able to move forward at the novel’s end but slavery will continue to shadow her life as an individual and America as a nation. The physical materiality of memory represented in Beloved affirms the link between historical events and the supernatural in The Lady Matador’s Hotel. At the beginning of the novel, Aura muses on the state of her country as she serves military men who’d she fought against as a rebel during the civil war: Aura is convinced that the entire country has succumbed to a collective amnesia. This is what happens in a society where no one is permitted to grow old slowly. Nobody talks of the past, for fear their wounds might reopen. Privately, though, their wounds never heal. (García 9) However, when Julio, the ghost of Aura’s brother, asks her to avenge his death, he begins to reopen these wounds again, reminding his sister that “there’s a place in the universe where memories are written down, where nothing is forgotten” (García 50). Though both individual and national insomnia, figurative and literal, is a central theme of many magical realist texts including One Hundred Years of Solitude, García reminds readers that there’s a supernatural recording of earth’s history that supersedes human memories and historical accounts. According to Julio’s ghost, there is a complete and correct version of history that can perhaps correct the wrongdoings of dictatorships such as those depicted in The Lady Matador’s Hotel. Just as there are limits on the living, there are limits on the dead. The ghost seems limited in his abilities to act because he can only appear on the roof, illustrating the dead’s dependence on the living. Aura recognizes that Julio has more knowledge than she because he’s dead but he refuses to share what he’s learned with her. In addition to revealing the connection between historical events and a supernatural historical record, the figure of Julio’s ghost politicizes Aura’s role at the hotel and the action that comes to take place there. His appearance on the Miraflor’s roof reminds Aura “the struggle is [her] personal burden” (11). This makes her feel as if “she’s serving both the living and the dead” (153) rather than herself. At the moment she slices the colonel’s throat with her knife, Aura realizes that “the last word in history…must be fought for again and again” (193). Ironically, it’s through murdering the colonel that Aura can move toward a life of action rather than waiting, “the verb that most defines her life” (152). Houses, Hotels, & History Though they houses of all three novels function as a focal point for the connections between families and politics, they also symbolize the text’s perspective on history. McClintock describes the family as a “trope for figuring historical time” where social hierarchy and historical change are “portrayed as natural and inevitable, rather than as historically constructed and therefore subject to change” (45). Úrsula’s perspective on the circularity of history disables Macondo from creating its own history. When they allow their history to be determined by outside groups, the Buendías succumb to the illusion of historical change as natural and inevitable. The insomnia plague that takes place symbolizes a collective loss of memory and historical awareness that allows the forces of modernity to ravage Macondo. Simas writes that the “vicious cycle of social injustice and oppression” that overwhelms Macondo “acts as a metaphor for the social condition of Latin America” (Simas 191). The invasion of these forces represents the novel’s second conception of time that drives the narrative to its apocalyptic end. Márquez symbolizes the narrative’s merging together of circular, ahistorical and linear, chronological conceptions of time through the image of a gyrating wheel. Pilar Ternera, the novel’s illegitimate matriarch, divines Macondo’s eventual return to its primordial sources: There was no mystery in the heart of a Buendía which was impenetrable for her because a century of cards and experience had taught her that the history of the family was a machine with unavoidable repetitions, a turning wheel that would have gone on spilling into eternity were it not for the progressive and irremediable wearing of the axle. (Márquez 396) Erikson points out the difference between “the novel’s metaphorical presentation of Latin American history and the characters’ ideological apprehension of their own history” (Erikson 199). The eschatological progression of time in the novel reflects Márquez ’s representation of Latin America looking too much toward an idealized past while allowing outside forces to define its history. As Aureliano reads his family history written by the gypsy Melquiades, the wind, full of “voices from the past” picks up and finally wipes out Macondo and “exiles [it] from the memory of men” (Márquez 416-417). The destruction of the Buendía mansion and its inhabitants at the novel’s conclusion symbolizes the self-destructive nature of Latin American history due to a belief in the cyclical nature of time. Another type of erasure takes place in Beloved though the physical structure of 124 still stands at the end of the novel. The questions surrounding Beloved’s identity and Morrison’s suggestion that her character also includes the already-crawling? baby and the African slaves who died on the ships during the journey through the Middle Passage complicate her exorcism and therefore Morrison’s representation of history. Though Beloved ends with her exorcism from 124, the unspeakable story of slavery “continues to haunt the borders of a symbolic order that excludes it” (Wyatt 226). In the last section, Morrison describes 124 as quiet—the voices have been silenced. However, the structure of 124 memorializes the traumatic past of American slavery. Kawash writes, “American literature frequently figures the nation as a house haunted by the national shame or repressed trauma of slavery” (Kawash 70). Though the voices have quieted and the stories have been repressed so that the characters can make “some kind of tomorrow” (Morrison 275) for themselves, the national specter of slavery continues to haunt American history. In The Lady Matador’s Hotel, the Hotel Miraflor itself serves as a transitional home where characters of different cultures and ethnicities interact with each other, which reflects the global postmodern condition. Nearly everyone has become part of a diaspora and the traditional institutions used to concentrate power come into question. The colonel’s murder takes place at the same time a bomb detonates at the Hotel Miraflor, signaling the people’s affirmation of agency against governmental and militaristic institutions. Aura’s personal act of murdering the colonel changes the country’s political landscape and allows her to move on from reopening the wounds of the past. The remaining characters flee from the Hotel Miraflor for new lives. The dispersal asserts the theme that no one can go home (García 203) and questions whether a traditional conception of home even exists in the present age. Zamora’s concept of “semantic duplicity” (30) establishes the importance of physical objects in magical realist texts, which tend to conflate objects with ideas. Architectural structures are not only central to the physical world of these particular narratives, they’re metaphorical centers of power contestations and bridges to the realm of the supernatural. As domestic spaces, houses possess a particular connection to female characters, especially the matriarchs. Families are also associated with houses while questions regarding adopted families and diaspora surround the figure of the hotel. Houses are of a dual nature, functioning both as prisons and sanctuaries to their inhabitants. The hotel serves as a location where strangers meet and interact, their perspectives and identities conflicting with one another. Both structures represent a liminal space that connects the living and the dead—earthly history and ghostly politics. Finally, the structures house memories of individual and communal trauma. Each undergoes a unique transformation, but those that survive are simultaneously alive and memorialized, representative of the ever-present influence of the past on the present. Works Cited Brogan, Kathleen. Cultural Haunting: Ghosts and Ethnicity in Recent American Literature. Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1998. Conner, Marc C. “From the Sublime to the Beautiful: The Aesthetic Progression of Toni Morrison.” The Aesthetics of Toni Morrison. Ed. Marc C. Conner. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2000. 49-76. Print. Dreifus, Claudia. “Playboy Interview: Gabriel García Márquez.” Conversations with Gabriel García Márquez. Ed. Gene H. Bell-Villada. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2006. 93-132. Print. Erickson, Daniel. Ghosts, Metaphors, and History in Toni Morrison’s Beloved and Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. Print. Faris, Wendy B. Ordinary Enchantments: Magical Realism and the Remystification of Narrative. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 2004. Print. García, Cristina. The Lady Matador’s Hotel. New York: Scribner, 2010. Print. Guibert, Rita. “Gabriel García Márquez.” Conversations with Gabriel García Márquez. Ed. Gene H. Bell-Villada. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2006. 31-58. Print. Kawash, Samira. “Haunted Houses, Sinking Ships: Race, Architecture, and Identity in Beloved and Middle Passage.” The New Centennial Review 1.3 (2001): 67-86. Print. Márquez, Gabriel García. One Hundred Years of Solitude. New York: Harper & Row, 1970. Print. McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge, 1995. Print. Morrison, Toni. Beloved. New York: Penguin, 1988. Print. Parkinson Zamora, Lois. “Swords and Silver Rings: Magical Objects in the Work of Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Márquez.” A Companion To Magical Realism. Ed. Stephen M. Hart, Ed. Wen-chin Ouyang. Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2005. 28-45. Print. Rodeño, Ignacio F. “Espacio, Cuerpo y Masculinidad Posmodernos en la Narrativa de Cristina García: El Caso de The Lady Matador’s Hotel.” The Latin Americanist 56.1 (2012): 57-72. Print. Roses, Lorraine Elena. “The Sacred Harlots of One Hundred Years of Solitude.” Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude: A Casebook. Ed. Gene H. Bell-Villada. New York: Oxford UP, Inc., 2002. 67-78. Print. Simas, Rosa. “A ‘Gyrating Wheel.’” Critical Insights: Gabriel García Márquez. Ed. Ilan Stavans. Pasadena: Salem P, 2010. 176-215. Print. Wyatt, Jean. “Giving Body to the Word: The Maternal Symbolic in Toni Morrison’s Beloved.” Critical Essays on Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Ed. Barbara H. Solomon. New York: G.K. Hall, 1998. 211-232. Print. Upstone, Sara. “Domesticity in Magical-Realist Postcolonial Fiction: Reversals of Representation in Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children.” Frontiers 28.1-2 (2007): 260284. Print.