Education Preparedness & Response Drought Affected Areas in the

advertisement

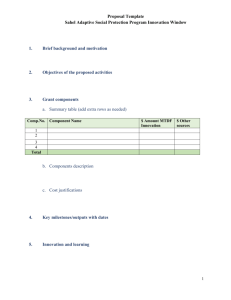

Education Preparedness & Response Drought Affected Areas in the SAHEL Zone 1. Situation Overview (1 page) 1.1. Education Situation Overview Approximate xx% of the land in the Sahel belt is expected to be affected by severe drought – especially Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, North Cameroun, North Nigeria and Senegal (North, St. Louis, Matam). Due to this imminent drought crisis, the education of an estimated xx children is expected to be disrupted. Countries xy are expected to be the worst affected in terms of access to quality education, many of these countries having education indicators way below the national average already prior to the drought. The drought is expected to have an adverse impact on children’s access to quality education in the region. For instance, some families might loose livestock due to failed rainfall and become unable to raise school fees and others might be displaced with their animals to seek new pasture and water for survival. As a result, the children have to leave schools and their learning will be disrupted temporarily or even forever. In some countries such as Chad and Niger, pastoralist families are foreseen to migrate from one place to another due to scarcity of water, pasture and food, the result being that education of an estimated xx children will be disrupted in these areas. Some schools in arid districts are expected to be over crowded with drought-affected children who might relocate to new areas, whilst others might experience very low rates of attendance. It can be expected that schools do not have the capacity of absorbing the influx of new arrivals, resulting in poor quality teaching in classrooms and serious shortage of meals and education materials in these schools. Girls might less likely go to school, especially in arid districts, which are prone to chronic drought. The Gender Parity Index (GPI) might become as low as xx in these regions. Reasons for the low female enrolment might be the unavailability of boarding or mobile schools and lack of access to hygiene and sanitary items in schools. In addition, some of the drought-affected countries are also vulnerable to sporadic conflict and flood shocks, which is proven to hamper children’s access to education. Thus, there is a need for both immediate preparedness and response planning as well as long-term development support at regional, national and sub-national levels. This, in order to increase efficiency in planning and fast track the collective sector responses. Key challenge is, that the Education Cluster remains underfunded and the supply intervention reaches currently (insert date) only xx children (mostly reached by UNICEF alone) out of the estimated xx. There is an acute need to mobilise more resources and scale up the response and reach as a whole. 1.2 High risk rural primary schools in drought-affected areas High-risk rural primary schools in drought-affected areas are typically characterised by: Unavailability of food and water on the premises of schools Absence of sanitary latrines and hygiene practices including hand-washing Serious shortage of basic stationary and teaching and learning materials Majority of children limited or no school furniture General sub-standard learning spaces in terms of semi-permanent building, crowded seating arrangements and insufficient amount of light in classrooms Prevailing teacher-centered learning practices Unavailability of teacher spaces for preparation and socialisation Absence of playgrounds and sports and recreational opportunities Diminishing financial and labour support by Parent Teacher Associations and community due to financial constraints and preoccupation with food and water security Inadequate supervisory mechanisms and support to school heads and teachers from (zonal) Education offices Insecure and unsafe learning environments without adequate protection and psycho-social wellbeing of students and teachers Isolated materially deprived and un-stimulating learning environments for students and teachers alike Prolonged absence of a significant number of children due to migration of pastoralist families during peak months of the drought Low rates of enrolment attendance completion and learning outcomes High rates of over aged children due to late enrolment in primary school Pre- and primary schools with a great need for technical and financial support for acute and long term needs 1.3 Lessons learned HoA: The following lessons learned can be drawn from the HoA crisis and a respective response would need to be adapted to the Sahel context: Shortage of resources: Due to the increased number of children, the classrooms are overcrowded with education resources inadequate - i.e. text books, exercise books, teaching, learning and recreational materials. Scarcity of school meals: Increased enrolment in primary schools and ECD centers can put a lot of pressure on the school feeding program. Lessons learned show that food rations per child have reduced as schools are cooking the recommended rations, leading to some children missing out on meals. The school meals are often the only meal for these children in disadvantaged communities. Lack of water access: Water in schools is scarce across the area. Out of xxx primary schools in xxx arid districts, xxx schools (xx%) have no access to water sources. Temporary drop-outs: Temporary drop-outs are being recorded since irregular attendance increases due to pressure on children to contribute to the survival of the families through water fetching, income generating activities and domestic chores to free up the time of their parents. Inadequate boarding supplies: Boarding school is the most promising way to provide both food security and education to nomadic children in drought-affected areas especially. However, the schools face serious capacity gaps as the already existing facilities are either overstretched, dilapidated or non-existent. Some boarding schools do not have sufficient facilities and supplies (i.e. beds, mattresses). Consequently, students have to sleep on the floor of the dormitory or even outside. Gender preference: Boy preference in schooling is prevalent among many communities. Girls are less likely to go to school in most counties. Post-primary education: Secondary schools are more or less affected by the high food prices and lack of fees payment according to head teachers in several districts. 2. Saving lives and responding to short-term crisis (1/2 page) 2.1 Why invest in education during emergency? Live-saving and life-sustaining needs: Education is a life-saving process since it provides children with safe spaces, information and skills, psycho-social support and stimulation that complement nutrition interventions necessary for their healthy growth. It sustains the life of children caught in conflict or disaster by providing a sense of stability, normalcy and even hope for the future. The process helps develop their recovery and start rebuilding their life after trauma. As a life-saving intervention for children in pastoralist communities, support for boarding schools (if applicable – see lessons learned HoA) is critical since they are the only safe haven for the nomadic children whose livelihoods have been swept away by the ravaging drought or who are left behind by their parents who moved with the livestock to far distances. In most of the drought-affected districts, schools are seen as the only option for feeding their children, and parents are even bringing their two- to three-year-old children to access food in the schools. Quality learning needs: Importantly, a sudden influx of new arrivals in some schools is expected to undermines quality of education as the government system does not allow for swift and flexible transfer of school grants which are supposed to cover tuition costs (lessons learned HoA – adapt to Sahel context). When children drop-out due to poor learning, they are even less likely to re-enrol because the drop-out is no longer associated with the drought but rather with poor quality of education itself. This causes chronic impact on quality learning achievements. Their learning opportunity can be lost forever, impacting the healthy development of the child and the long-term growth of the community. 2.2 Immediate Education Responses: All children have the Right to a quality education in a safe, secure, healthy and stimulating environment conducive to their overall development and knowledge and life-skills acquisition. The following actions are recommended in support of the high-risk schools and students: In response to serious shortage of education supplies at schools, it is recommended for UNICEF and partners to conduct immediate supply interventions in close coordination with the Ministry of Education and District Education Offices (DEOs) in each of the drought-affected areas. Provision of education supplies aims to enable students to continue meaningful learning during emergency. The priority target is focused on primary schools with new influx and schools that have not yet registered with Free Primary Education grants earmarked for purchasing textbooks and notebooks (lessons learned HoA – adapt to Sahel context). In line with each Government’s priorities, UNICEF and partners are recommended to support the Ministry of Education to implement the Nomadic Education Policy (where applicable – lessons learned HoA – adapt to Sahel context). This policy defines ways for nomadic children who have no access to regular schools located far from their communities to participate in basic education through improved access to low-cost boarding or mobile schools within their communities. In addition, based on lessons learned from the HoA the following interventions are recommended to take place: Provision of school feeding and adequate supply of safe water (collaboration with Nutrition and WASH) Instalment of sanitary latrines and demonstration of hygienic practices (collaboration with WASH) Support for stationary and basic teaching and learning materials to all students and teachers, including school in a box and early childhood development kits. Provision of school furniture for students and teachers Introduction of physical and recreational activities, including distribution of recreational kits (collaboration with Child Protection) Maintenance and renovation of learning spaces Organisation of in-service multi-grade teacher training Establishment of school based management training for school heads and PTA members Arrangement for INEE training for zone and education personnel on assessment, analysis, planning and action Zonal emergency task force training on prevention, preparedness, mitigation and action planning Develop capacity of District Education Offices (DEOs) and head teachers on Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Organise life-skill trainings and Talent Academy activities for young people Policy consideration of revised primary education calendar for pastoralist areas chronically affected by drought with livelihood and migration practices of population Policy consideration on provision of mobile schools for highly affected pre- and primary school population in high risk zones Development of inter-agency and inter-sectoral action planning including fundraising appeals for drought-affected high-risk schools and students. Camp Settings: Not applicable yet but might be if there is a large population migration; in these case it is recommended to maintain close coordination between the MoE, UNICEF and partners in supporting temporary learning spaces and delivering education materials for children to continue learning during emergency; this may include aiming at improving quality of education through training of teachers, construction of semi-permanent schools (classrooms), setting up school tents for displaced children as well as ECD centers and Child Friendly Spaces (collaboration with Child Protection). In addition, provision of education, recreation and ECD kits in temporary (learning) spaces, textbooks, teaching and learning material as well as support to accelerated learning programs for children, catch-up education programs for out-of-school children and youth and organisation of life-skills training and youth talent development activities including sports events in coordination with secondary schools and local NGOs to reach displaced youth. With UNICEF’s recent re-focus on equity it is recommended for the intervention put emphasis on the most marginalised children, especially girls in rural and/or nomadic settings. The provision of boarding supplies, hygiene kits, mobile school kits, as well as boarding school management training would facilitate the improved enrolment and retention of girls (Lessons learned HoA). Education Cluster The Education Cluster (in some countries co-led by UNICEF and xx – to be verified in the Sahel context, currently only Chad has an active and officially adopted Education cluster system in place – recommended to activate EiE working groups in other countries and to activate Education Cluster in Niger) plays a key role in ensuring the inter-agency coordination and collective response with the Ministry of Education. It also leads the development of education database and analysis of primary and ECD enrolments in drought-affected districts. It is recommended to undertake a joint rapid assessment (led by the Ministry of Education and the Education Cluster) in drought-affected areas. Summarised here is a selection of the recommended actions to be addressed by the Education Cluster, colead agencies and cluster partners: Continued strengthening of partner capacity: Work should continue to support education partners to mainstream emergency programming into their development work to ensure that progress gains are not lost due to conflict and disaster. The cluster should also seek to identify more emergency-focused partners who can support education programming. Additional Capacity at the Ministry of Education: The Ministry of Education should appoint a position to work within the development partners coordination office focused solely on emergency response and risk reduction work, who can liaise with State Ministry of Education emergency focal points and national cluster partners Focus on Country-Level preparedness and prepositioning: In order to deal with the continued access challenges throughout the various countries it is recommended that further work be undertaken to roll-out emergency education support to country level (national and sub-national). This would include the further training of national and sub-national partners including the government on emergency preparedness and response as well as the continued prepositioning of emergency supplies down to district level. Demonstrating Education Cluster progress and need: Continue to make the case for education in emergencies to other humanitarian sectors, to OCHA and the HC and to donors. We need to better demonstrate the impact of emergencies on the education system and the children and teachers in drought affected regions of the Sahel as well as the impact of our interventions on their lives. Training for State and District Cluster Partners in Information Management: Work will need to be done to roll out the new Information Management System to all States, and to train State and Country Partners in the Cluster tools as well as good IM practices. Contextualizing the INEE Minimum Standards and Developing a Monitoring Framework: The Education Cluster should work to contextualize the INEE Minimum Standards to the local context in the drought-affected areas of the Sahel and provide guidance to partners on how to apply them in their programming. Using the Minimum Standards as a framework, monitoring tools also need to be developed to track the Cluster’s progress and ensure quality responses. Advocate for the development of an Education in Emergencies Policy: Work with the Ministry and other Cluster partners to develop a policy to complement the Education Act that outlines the Ministry’s stance on emergency response in the education sector. Further prioritization of cross-cutting issues: Emergency Education can be an opportunity for innovation and change. The Cluster will need to dedicate resources and technical capacity to support partners to undertake community mobilization and teacher training initiatives to ensure the needs of the hardest to reach children affected by emergencies in the drought-affected areas of the Sahel (gender, inclusion etc.). Continued collaboration with other Clusters: The Education Cluster should continue to coordinate wherever possible with other Clusters to strengthen the education response and demonstrate the role education can play in supporting the achievement of other sector’s objectives. The development of Emergency Teacher Training modules on Child Protection, Psychosocial Support, Health and Nutrition, and WASH are recommended (see also lessons learned South Sudan). Continued focus on improving programmatic leadership of co-lead agencies: Both Education Cluster agencies (where applicable) should continue to develop and strengthen their programmatic responses to acute emergencies in. As lead-agencies, provision of education services should be the first priority in any emergency response. Ensuring both organizations have the capacity and systems to lead in this area will be vital. 3. Building systems, strengthening resilience and ensuring sustainability (1/2 page) Poverty alleviation needs: Education is a way to mitigate the long-term impact of emergency on the well-being of children, and it becomes an effective means of the recovery and poverty reduction in the long run. Returns to education investment are critical even in emergency situations because most of the children who drop out due to emergency disaster are unlikely to re-enrol at a later stage. Their education opportunity can be lost forever. It implies that the future development of their knowledge, skills and productivity, and their socio-economic opportunities in the society are reduced and limited at all levels. This leads to a severe impediment to overall poverty alleviation. From the point of view of the education policy implication, the drought impact on education threatens progress towards the achievement of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Education for All (EFA) by 2015 to which Governments of the affected Sahel countries have been committed. In particular, delivering quality education to nomadic communities is one of the most challenging and urgent issues even during the normal situations in these areas. To meet MDGs and EFA, there need to be more efforts and interventions to allow nomadic children to have improved and continued access to education opportunities during and after emergency situations. The Nomadic Education Policy must be further supported and implemented to promote access and quality of education for nomadic children drought-affected countries (where applicable – adapt to the Sahel context – see lessons learned HoA). Capacity development interventions: UNICEF and partner’s Education emergency interventions are recommended to be linked with a sustainable approach to strengthening school-based emergency preparedness through the capacity development of the central and district education partners and boarding school head masters and teachers. This is to increase safety and protection of children in boarding schools whilst at the same time building resilience of the schools and strengthening management capacity of mitigating the risk of future disasters. These activities should be aligned with the Nomadic Education Policy (where applicable – see lessons learned HoA – adapt to Sahel), which is the Ministry’ of Education’s strategic approach to education of pastoralist communities as well as the Ministry of Education’s Emergency Preparedness and Response plans. It is also recommended for UNICEF and partners extending its support to out-of school youths to develop their potential talent in drought-affected arid areas. This is designed and conducted in line with the regular program approach and can include the following: Develop key training manuals regarding the Child-Friendly School (CFS) school management together with the Ministry of Education officials Organise a 5-day training on CFS school management for xx head teachers and district education officials to reinforce their capacities of school management, school safety and emergency preparedness Coordinate with implementing partners to organise a rapid school readiness initiative to enable xx children to enrol in ECD and primary schools and have decent learning during emergency Apply a national talent academy approach in developing the traditional talent capacities (i.e. music, craft skills) of approximate xx out-of-school youths aged 15 – 24 who are affected by drought (if applicable – adapt to Sahel – see lessons learned HoA). Rolling out Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) to boarding schools: Following the above interventions, the drought-stricken schools would be adequately staffed with teachers who are trained and equipped with proper knowledge of safe, protective and health-promoting school management even during the context of emergency. This leads the schools to functioning as a platform to provide children with quality teaching and learning, food support, safe water and sanitation, safety and protection, community participation and emergency preparedness which are all supported by the national Governments, UNICEF and partners. On top of its current regular and emergency interventions, UNICEF in collaboration with partners should aim at a strategic plan to roll out the DRR capacity development of schools within all the emergency-prone arid districts within the WCAR region in 2012.