Handout: Case Study of Emergency Education Response Case

advertisement

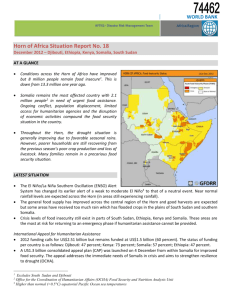

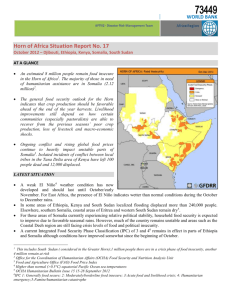

Handout: Case Study of Emergency Education Response Case Study: protracted crisis characterised by drought, food insecurity and displacement1 Location and situation: A large area across the Horn of Africa, bordering Somalia is suffering from the impacts of a protracted drought and food insecurity crisis. This case study presents the current humanitarian situation, for a large region within one of the affected countries. The information includes its impact on various sectors (including education), response to date and planned response Background: Last year failed seasonal rains were followed by poor belg rains which were late in onset, inadequate in amount and uneven in distribution. This has had profound impacts: a humanitarian crisis has been announced by the international community, with a primary focus on the food security situation. Since the crisis was announced, a primary response focus has been on the nutrition and health sectors. The following concerns dominate the current response discussions; The combined effects of drought, food price increases, and insufficient resources for preventive measures have resulted in increased malnutrition among children. Over the last five months increased admissions rates of acutely malnourished children into Therapeutic Feeding Programmes (TFPs) were reported while current estimates indicate a 16 per cent increase in acute malnutrition among children from the previous year. Acute Watery Diarrhoea (AWD) and other disease outbreaks pose an increased threat to children already suffering from malnutrition. A current concern is how to prevent the disease from spreading during the migration of pilgrims and owing to large-scale displacement (see below). The outlook is further complicated by the high risk of large-scale flooding in some areas: a previous consequence of extended drought periods. Moreover, since January, the number of refugees from Somalia has been increasing, with current levels estimated at 2,500 refugees per day being registered by UNHCR, which reports the pre-existing refugee caseload at 110,000. High levels of moderate acute malnutrition and severe acute malnutrition are reported among the refugee population. Education sector in crisis Besides the immediate threat of malnutrition and dehydration, children are also very vulnerable to being forced to drop out of school. By April of last year the school drop-out rate reached 38 per cent in the south, an increase from 30 per cent since February. Children are dropping out of school in order to work or because their families have to move on with their flocks in search of better pastures. Moreover, many schools in drought-stricken areas shut down because their wells run dry. Even before the crisis, the education system was under strain in the drought affected areas. Enrolment rates were among the lowest in the country - 21 per cent overall against the national average of 79 per cent. Schools also lacked enough classrooms, furniture, 1 This case study is intended to be indicative rather than an accurate representation of any time or geographical bound situation for this region. It is based on sit reps and available documentation detailing humanitarian response initiatives across the Horn of Africa over the last 5 years (documentation covers both the 2006 and 2011 crisis). textbooks, sporting facilities and toilets and there were not always enough qualified teachers were, school sporting facilities and toilets. The situation has become so bad that some communities are being displaced on mass as social infrastructure collapses and forces families to abandon their homes, depriving children of their education. The following testimonials were collected from children in affected areas; E., 17 year old girl from a pastoralist community ‘The drought killed off my family's 500 head of cattle. Even though the rains finally arrived last month, it was too late. With the death of the last cow, we are not able to pay my school fees.’ ‘I feel so much pain because my friends from school have finished their exams and moved on…but I'm stuck at home and nobody is helping me. Nobody knows my pain. Sometimes I go three days with no food. I spend the day cleaning, gathering firewood and preparing any food we have. But the situation is bad and now we will likely migrate in search of water and grazing land.’ ‘The future looks dark: I cannot see anything coming.’ M. 12 year old boy from the Somali region ‘I used to enjoy going to school with my big sister. We walked to school together, we were learning together. When I didn’t know the answer she used to tell me.’ ‘Then the drought spread to Gode, and our sheep and goats started to die. We had no income or food. My parents decided to take my sister out of primary school and get her working.’ ‘Lots of my classmates have also dropped out of school and others only come to school for one or two days every few weeks. Most of us are also always hungry which make the classes harder.’ ‘Last week after exams the teachers left and the school closed. Now my parents are saying I may have to leave school to earn money. I could probably work shining shoes but I’m waiting to go back to school: I want to go to university.’ Initial emergency education response Education response was slower than response in other sectors, hampered by lack of funding and low prioritisation within the humanitarian community. However, following a comprehensive needs assessment that was undertaken by Education Cluster members six months ago education interventions are now underway. To date, many interventions have been about providing water to the schools, since most of the schools are located in areas without permanent water sources. In addition to the provision of a WASH package for some of the most vulnerable schools, measles vaccination coverage is also being implemented across the region. An overarching key education sector concern has been to raise awareness within the humanitarian community of the impact of the food insecurity situation on the education system. A key goal within this is to mobilize more funding to roll out additional mobile health and nutrition teams and to support training for former classroom assistants and older children to play a greater role in implementing formal and non-formal learning opportunities. During the needs assessment that was conducted by the education cluster, there was also a recognised need to focus on out-of-school adolescents who have missed the opportunity of formal education. As such, some education cluster partners are looking to conduct activities that seek to develop life skills amongst adolescents to contribute to early recovery/conflict resolution and to emphasize the role of girls. Interventions are also taking place against a backdrop of ongoing support to the National Authorities to launch an in-depth review of the education system and to fund the training of more teachers and supply basic education and play equipment. The Ministry of Education has stressed that those capacity-building components of activities should seek to support the development of local and national institutions to assess the situation, provide educational opportunities, coordinate the response and monitor the impact of education interventions. As such local and regional Ministry Staff played a key role in the implementation of the needs assessment, while national level Ministry staff provided key baseline data and ensured that the data collection methods were in line with the Ministry data collection systems to allow for time comparable data. The education cluster also has to manage coordination with other sectors whose work both impacts on education and utilises its resources and infrastructure. From the perspective of the education cluster it is hoped that these health, nutrition and clean-water initiatives will help return some form of stability to pastoralists’ lives, thereby giving them the opportunity to send their children back to school. Priority activities outside of the education sector have included ongoing support to mobile health teams, increased nutrition response, water trucking and AWD preparedness and response. Most recently, in partnership with WFP, the education cluster has sought to support a school-feeding project that is being undertaken in some of the most vulnerable communities, with the aim to retain more than 18,000 children in school. Internally Displaced Persons: In addition to the efforts to support communities to remain where they are, Education Cluster members are also conducting specific education outreach for internally displaced populations. Temporary learning spaces and educational materials have been provided, together with appropriate incentives such as school feeding. Moreover a ‘back-to-school’ campaign is being planned that will cover all areas of Ethiopia, but with a particular focus on girls and IDPs. Somali refugees: UNHCR coordinates all multi-sector assistance and protection for refugees, with other agencies providing ad hoc support as requested. This cooperation is not yet systematic or formalized however, which has resulted in some gaps whereby host communities have received less support than refugees, resulting in some tensions. The continued influx of refugees in the Somali Region will require an updated needs assessment and partnerships to address refugees concerns, given the ongoing scale of the situation at the border with Somalia. Beyond the initial response (managing the protracted crisis) In addition to activities already underway, a back to school campaign is also being planned and education cluster members have highlighted the following activities in project documents submitted to the UN Consolidated Appeals Process Flash Appeal. Provide tented learning spaces and educational material for 10,000 displaced children; Provide rapid training to displaced teachers and community education committees to ensure effective management and sustainability of schools and learning spaces; Ensure girls’ access to educational opportunities through affirmative action; Train national and local authorities in conducting rapid assessments, undertaking advocacy and complying with the Minimum Standards for Education in Emergencies (INEE); Train national and local authorities in management functions to support a rapid response for education in emergencies; Support the development of the education management information system (EMIS) to ensure that information is collected on the number and location of children displaced or affected by emergency; on the availability and conditions of school facilities; and on the availability of learning materials and teachers. Youth-to-youth (Y2Y) education for refugee adolescents through information communication technologies via existing equipped youth multipurpose centres, and through peace education via participatory education theatre and ongoing youth broadcasting initiatives.