Dukes` classification

advertisement

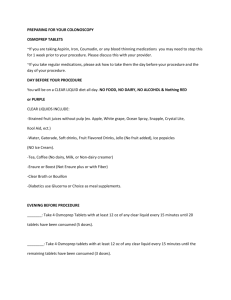

Staging colon cancer There are several staging systems that are used such as Dukes, tumour–node– metastasis (TNM). Dukes’ classification was originally described for rectal tumours but has been adopted for histopathological reporting of colon cancer as well. Dukes’ classification for colon cancer is as follows: A: confined to the bowel wall; B: through the bowel wall but not involving the free peritoneal serosal surface; C: lymph nodes involved. Dukes himself never described a D stage, but this is often used to describe either advanced local disease or metastases to the liver. TNM classification Carcinoma of the colon usually occurs in patients over 50 years of age, but it is not rare earlier in adult life. A careful family history should be taken. Those with first-degree relatives who have developed colorectal cancer at the age of 45 years or below are at high risk and may be part of one of the colorectal cancer family syndromes. Symptoms and signs of colorectal cancer ■ Right-sided tumours: iron deficiency anaemia, abdominal mass ■ Left-sided tumours: rectal bleeding, alteration in bowel habit, tenesmus, obstruction ■ Metastatic disease: jaundice, ascites, hepatomegaly; other symptoms and signs from rarer sites of metastasis. Methods of investigation of colon cancer Flexible sigmoidoscopy; the 60-cm, fibreoptic, flexible sigmoidoscope is increasingly being used in the out-patient clinic or in special rectal bleeding clinics. Colonoscopy; This is now the investigation of choice if colorectal cancer is suspected provided the patient is fit enough to undergo the bowel preparation. It has the advantage of not only picking up a primary cancer but also having the ability to detect synchronous polyps or even multiple carcinomas, which occur in 5% of cases. However, one must be aware of a small risk of perforation and also the failure to get to the caecum in 10% of cases, even by experienced endoscopists. Double-contrast barium enema; is used when colonoscopy is contraindicated. Ultrasonography; is often used as a screening investigation for liver metastases over the size of 1.5 cm, and CT is used in patients with large palpable abdominal masses, to determine local invasion, and is particularly used in the pelvis in the assessment of rectal cancer. Spiral CT; is particularly useful in elderly patients when contrast enemas or colonoscopy are not diagnostic or are contraindicated. Virtual colonoscopy; is effective in picking up polyps down to size of 6 mm. This may even replace colonoscopy as the standard investigation in the future. Urograms; have a role in left-sided tumours where there is evidence of hydronephrosis on CT or ultrasound. Preoperative preparation The most commonly used method is dietary restriction to fluids only for 48 hours before surgery; on the day before the operation, two sachets of Picolax (sodium picosulphate) are taken to purge the colon. In addition, a rectal washout may be necessary. A stoma site is carefully discussed with the stoma care nursing specialist and anti-embolus stockings are fitted; the patient is started on prophylactic subcutaneous heparin, and intravenous prophylactic antibiotics are given at the start of surgery. When intestinal obstruction is present, preparation in this way may precipitate abdominal pain, and it may be safer to use an on table lavage technique at the time of the operation. The test of operability The abdomen is opened and the tumour assessed for resectability. 1 The liver is palpated for secondary deposits, the presence of which is not necessarily a contraindication to resection because the best palliative treatment for carcinoma of the colon is removal of the tumour. 2 The peritoneum, particularly the pelvic peritoneum, is inspected for signs of small, white, seed-like, neoplastic implantations. Similar changes can occur in the omentum. 3 The various groups of lymph nodes that drain the involved segment are palpated. Their enlargement does not necessarily mean that they are invaded by metastases, because the enlargement may be inflammatory. 4 The neoplasm is examined with a view to mobility and operability. Local fixation, however, does not always imply local invasion because some tumours excite a brisk inflammatory response. Operations The operations to be described are designed to remove the primary tumour and its draining locoregional lymph nodes, which may be involved by metastases. Lesser resections are indicated, however, should hepatic metastases render the condition incurable surgically. There is some evidence that early division of major blood vessels supplying the involved colon (no-touch technique – Turnbull) can slightly improve the number of curative operations. Carcinoma of the caecum or ascending colon; is treated when resectable by right hemicolectomy. Carcinoma of the transverse colon ; When there is no obstruction, excision of the transverse colon and the two flexures together with the transverse mesocolon and the greater omentum, followed by end-to-end anastomosis, can be used. An alternative is an extended right hemicolectomy. Carcinoma of the splenic flexure or descending colon; The extent of the resection is from right colon to descending colon. Sometimes, removal of the colon up to the ileum, with an ileorectal anastomosis, is preferable. Carcinoma of the pelvic colon; The left half of the colon is mobilized completely. So that the operation is radical, the inferior mesenteric artery below its left colic branch, together with the related paracolic lymph nodes, must be included in the resection. Laparoscopic surgery However, its role needs to be accepted with an element of caution. It is technically demanding with a long learning curve. When a growth is found to be inoperable In the upper part of the left colon, an ileostomy is performed. In the pelvic colon, a left iliac fossa colostomy is preferable. With an inoperable growth in the ascending colon, a bypass using an ileocolic anastomosis is the best procedure. Screening Faecal occult blood testing of people aged 60–69 years can reduce the mortality risk of colorectal cancer by about 15%. Those who test positive for faecal occult blood tests are then offered colonoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy can also be used as the initial screening tool, and early results from a clinical trial look promising. Hepatic metastases It is important not to biopsy hepatic metastases as this may cause tumour dissemination. Hepatic resection is usually performed as a staged procedure after recovery from colonic resection. Most wait 12 weeks before restaging. By doing this, those with aggressive disease are excluded from further drastic (radical) surgery. Reports have shown 30% 5-year survival following hepatectomy for colorectal cancer metastases. At present, the criterion for resection is fewer than three lesions in one lobe of liver. Irresectable symptomatic hepatic metastases may be suitable for other treatments including cytotoxic drugs or ablative treatments Traumatic rupture The intestine can be ruptured with or without an external wound – so called blunt trauma. The most common cause of this is a blow to the abdomen that crushes the bowel against the vertebral column or sacrum; also, a rupture is more likely to occur where part of the gut has been fixed, for example in a hernia, or where a fixed part of the gut joins a mobile part such as the duodenojejunal flexure. The patient will then have a combination of intra-abdominal bleeding and release of intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity, giving rise to peritonitis. Traumatic rupture of the large intestine is much less common. In blast injuries of the abdomen following the detonation of a bomb, the pelvic colon is particularly at risk of rupture. Compressed air rupture can follow the dangerous practical joke of turning on an airline carrying compressed air near the victim’s anus. Rupture of the upper rectum can occur during sigmoidoscopy and occasionally during the placement of rectal catheters for barium radiology. Traumatic rupture of the colon can occur during colonoscopy. The most common site is the sigmoid colon. Gunshot wounds injuries to the bowel have more serious consequences because of the introduction of debris from the patient’s clothing or the missile itself mixing with the bacteria in the patient’s gut. High-velocity missiles may cause extensive damage to the bowel over a much wider area than just the entry and exit wounds. Treatment Where rupture is suspected, a plain radiograph in the erect or lateral decubitus position will demonstrate the presence of free air in the peritoneal cavity or indeed in the retroperitoneal tissues. In almost all cases, an abdominal exploration must be performed and, in many instances, simple closure of the perforation is all that is required. In others, for example where the mesentery is lacerated and the bowel is not viable, resection may be necessary. In the case of the large intestine, small, clean tears can be closed primarily; if there is a large tear with damage to the surrounding structures and the adjacent mesentery, resection and exteriorisation may be used. Much depends on the amount of intra-abdominal soiling. In the case of retroperitoneal portions of the intestine, for example the duodenum, perforations can involve the front and back walls, and the duodenum in particular has to be carefully mobilised to check that a concealed tear is not overlooked. In all cases, the abdomen is washed out with saline and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are given.