Precarious Work Schedules in Low-Level Jobs: Implications

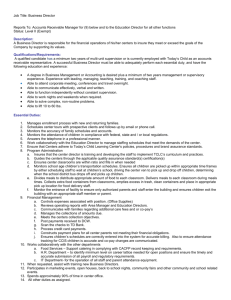

advertisement