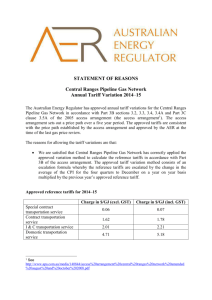

Issues paper Tariff structure statement proposals

advertisement