CIVIL LIBERTIES – limits on what government can do to you or take

advertisement

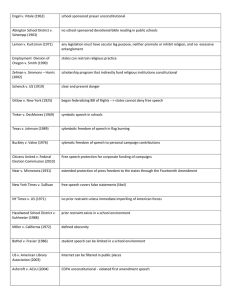

CIVIL LIBERTIES – limits on what government can do to you or take away from you; personal freedoms the government can’t take away from individual citizens In original Constitution: no suspension of habeas corpus except during rebellion or invasion no ex post facto laws or bills of attainder no religious oath for government office Bill of Rights: 1st – religion, speech, press, assembly, petition 2nd – right to bear arms 3rd – no quartering of troops 4th – search & seizure 5th – fair compensation for eminent domain, no self-incrimination or double jeopardy, due process 6th – trial rights - lawyer, jury trial, speedy trial, confront witnesses 7th – trial by jury for civil cases 8th – no excessive bail or cruel or unusual punishment 9th – individuals have other rights not listed 10th – reserved powers; states’ rights 14th: protects violation of rights & liberties by states due process clause – prohibits abuse of “life, liberty, or property”; guarantees civil liberties equal protection clause – guarantees civil rights Selective incorporation cases (ONLY THESE – except Barron – COUNT) Bill of Rights had been determined to only to protect you from Federal Government, not from States (Barron v Baltimore 1833) – creates concept of dual citizenship the 14th amendment was used in later court cases to incorporate the Bill of Rights into the due process clause so states would have to follow them also; it’s selective because not all amendments of the Bill of Rights have been incorporated – begins to dissolve dual citizenship. Gitlow v New York (1925) – incorporates freedom of speech by applying Schenck “clear & present danger test” to states (that had been a FEDERAL case); assumed protections of free speech & press applied to states Near v Minnesota (1931) – incorporates freedom of the press (no prior restraint) DeJonge v Oregon (1937) – incorporates right to assembly; arrested for attending Communist Party meeting Palko v Connecticut (1937) – some Bill of Rights guarantees (like freedom of speech) are so important that they must be applied to the states but protection against double jeopardy is not one; by 1969 Palko was overturned in Benton v Maryland (1969), incorporating “no double jeopardy” and Supreme Court had incorporated MOST (but not all) of Bill of Rights to the states West Virginia v Barnette (1943) – incorporates free exercise clause Wolf v Colorado (1949) – incorporates 4th amendment (search warrant/probable cause) to states but doesn’t require them to use exclusionary rule like federal government did Mapp v Ohio (1961) – incorporated exclusionary rule to states Gideon v Wainwright (1963) – incorporates right to counsel (lawyer) part of 6th amendment Griswold v Connecticut (1965) – incorporates “zone of privacy” (as created by the 1st, 3rd, 4th, & 5 th amendments & protected by 9th amendment) Miranda v Arizona (1966) – incorporates idea that all levels of government have a duty to inform suspect of his constitutional right (right to lawyer, remain silent, not selfincriminate) – 5th Duncan v Louisiana (1968) – incorporates right to jury trial in criminal cases of 6th amendment 3rd, & 7th amendments have never been incorporated, nor has excessive bail of 8th Freedom of Religion: Establishment clause Everson v Bd of Ed (1947) – using states funds to pay for busing to religious schools is constitutional Lemon v Kurtzman (1971) – created a 3-pronged test for state aid to religious schools: (1) secular purpose (2) can’t advance or inhibit religion (3) can’t entangle government excessively with religion Engel v Vitale (1962) – NY state law reading a state-composed prayer unconstitutional Wallace v Jaffree (1985) - Moment of silence for prayer or meditation unconstitutional Other rulings – prayer at official public school graduations unconstitutional (1992); organized, student-led prayer at public high school football game unconstitutional (2000); religious organizations must be able to use public school facilities before/after hours if you let other outside groups (2001) Free exercise clause – a law burdening “free exercise” of religion must be subject to strict scrutiny (government must show law is justified by a “compelling governmental interest” and is the least restrictive means for achieving that interest. Religious practices that endanger public safety or violate existing laws unconstitutional Children of Jehovah’s Witnesses can refuse to salute flag but can’t be denied life-saving medical treatment Coercion test Some justices propose allowing more government support for religion than the Lemon test allows. These justices support the adoption of a test outlined by Justice Anthony Kennedy in his dissent in Allegheny County v. ACLU and known as the “coercion test.” Under this test the government does not violate the establishment clause unless it (1) provides direct aid to religion in a way that would tend to establish a state church, or (2) coerces people to support or participate in religion against their will. Under such a test, the government would be permitted to erect such religious symbols as a Nativity scene standing alone in a public school or other public building at Christmas. But even the coercion test is subject to varying interpretations, as illustrated in Lee v. Weisman, the 1992 Rhode Island graduation-prayer decision in which Justices Kennedy and Antonin Scalia, applying the same test, reached different results. Endorsement test The endorsement test, proposed by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, asks whether a particular government action amounts to an endorsement of religion. According to O’Connor, a government action is invalid if it creates a perception in the mind of a reasonable observer that the government is either endorsing or disapproving of religion. She expressed her understanding of the establishment clause in the 1984 case of Lynch v. Donnelly, in which she states, “The Establishment Clause prohibits government from making adherence to a religion relevant in any way to a person’s standing in the political community.” Her fundamental concern was whether the particular government action conveys “a message to non-adherents that they are outsiders, not full members of the political community, and an accompanying message to adherents that they are insiders, favored members of the political community.” O’Connor’s “endorsement test” has, on occasion, been subsumed into the Lemon test. The justices have simply incorporated it into the first two prongs of Lemon by asking if the challenged government act has the purpose or effect of advancing or endorsing religion. The endorsement test is often invoked in situations where the government is engaged in expressive activities. Therefore, situations involving such things as graduation prayers, religious signs on government property, religion in the curriculum, etc., will usually be examined in light of this test. Neutrality While the Court looks to the endorsement test in matters of expression, questions involving use of government funds are increasingly determined under the rubric of neutrality. Under neutrality, the government would treat religious groups the same as other similarly situated groups. This treatment allows religious schools to participate in a generally available voucher program, allows states to provide computers to both religious and public schools, and allows states to provide reading teachers to low-performing students, even if they attend a religious school. It also indicates that the faith-based initiatives proposed by President Bush might be found constitutional, if structured appropriately. The concept of neutrality in establishment-clause decisions evolved through the years. Cited first as a guiding principle in Everson, neutrality meant government was neither ally nor adversary of religion. “Neutral aid” referred to the qualitative property of the aid, such as the funding going to the parent for a secular service such as busing. The rationale in Everson looked to the benefit to the parent, not to the religious school relieved of the responsibility of providing busing for its students. Later cases recognized that all aid is in some way fungible; i.e., if a religious school receives free math texts from the state, then the money the school would have spent on secular texts can now be spent on religious material. This refocused the Court’s attention not on the kind of aid that was provided, but who received and controlled the aid. Decisions involving vocational training scholarships and providing activity-fee monies to a college religious newspaper on the same basis as other student groups showed the Court focused on the individual’s control over the funds and equal treatment between religious and non-religious groups. In Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, the plurality decision clearly defines neutrality as evenhandedness in terms of who may receive aid. A majority of the Court continues to find direct aid to religious institutions for use in religious activities unconstitutional, but indirect aid to a religious group appears constitutional, as long as it is part of a neutrally applied program that directs the money through a parent or other third party who ultimately controls the destination of the funds. While many find this approach intuitively fair, others are dissatisfied. Various conservative religious groups raise concerns over diminishing the special place religion has historically played in constitutional law by treating religious freedom the same as every other kind of speech or discrimination claim. Strict separationist groups argue that providing government funds to religious groups violates the consciences of taxpayers whose faith may conflict with the religious missions of some groups who are eligible to receive funding using an “even-handed” approach. Free Exercise Clause Before 1990 SCOTUS used the compelling interest test to determine free exercise cases. The Rehnquist Court discarded the compelling interest test in the ruling that the a government no longer had to show a compelling interest in order to apply its general laws to religious practices 1993 The Religious Freedom Restoration Act was designed to restore the use of compelling interest test. Exempts people from laws and governmental actions that burden their religious freedom The RFRA was ruled unconstitutional in City of Boerne v. Flores decision in 1997, which ruled that the RFRA is not a proper exercise of Congress's enforcement power. Congress proposed the Religious Liberty Protection Act. RLPA provides that state and local government may not, absent a showing of compelling governmental interest and least restrictive means, substantially burden a person’s religious exercise: in a program or activity, operated by a government, that receives federal financial assistance; or in or affecting commerce with foreign nations, among the several States, or with the Indian tribes. Freedom of Speech: Ok to limit speech in certain circumstances – political, obscenity Schenck v US (1919) – “clear & present danger” (speech can advocate violence as long as it does not pose immediate danger) Gitlow v New York (1925) – speech supporting socialist revolution is illegal even if it doesn’t lead to law-breaking During Red Scare, court ruled ok to limit speech of communists; when over return to clear & present danger test Chaplinsky v New Hampshire (1942) – “fighting words” (speech that incites unlawful action) not protected speech Brandenburg v Ohio (1969) – government must prove danger from threatening speech is imminent Tinker v Des Moines (1969) – students wearing black armbands at school to protest Vietnam War is protected speech as long as not disruptive to school learning environment Texas v Johnson (1989) – laws prohibiting burning of US flag unconstitutional (symbolic speech) 2003 – ruled Virginia law prohibiting cross burning with “intent to intimidate” was constitutional Roth v US (1957) – obscenity is not constitutional protected speech or press Miller v California (1973) – 3 pronged test for obscenity: 1) violate community standards & appeal to prurient (nasty/disgusting) interests 2) show offensive sexual conduct 3) lacks seriously redeeming social, literary, artistic, political, or scientific merit Reno v ACLU (1997) – Communications Decency Act (no pornography on Internet) unconstitutional Freedom of Press: Near v Minnesota (1931) – prior restraint is unconstitutional; upheld in New York Times v US (1971) – Pentagon Papers case (said government had not proved threat to national security) Libel - false written statement that damages someone’s character is NOT protected speech but hard to prove on public figures – they must prove actual malice (New York Times v Sullivan – 1964 – freedom of press is more important than damage to public figure’s reputation; also Falwell v Hustler Magazine - 1988) Search & Seizure: In most circumstances must have a warrant from a judge, which police obtain by convincing him that they have probable cause (evidence crime has been committed) Mapp v Ohio (1969)- incorporated Exclusionary rule – illegally obtained info (without a warrant) can’t be used in trial Inevitable discovery – 1984 – police can use illegally obtained evidence if they can prove they would have eventually obtained it in a legal manner US v Leon (1984) establishes good faith exception (if police believed they had legal warrant – even if it turns out later it wasn’t – then evidence could be used in court) Later exceptions – can search garbage cans; can search ANYWHERE in a moving vehicle that was pulled over for minor traffic violations Rights of the Accused: Miranda v Arizona (1966) – police overturn his conviction because he wasn’t informed of his right to remain silent or to have a lawyer; protects against self-incrimination; police now read “Miranda” warning whenever suspect taken into custody (later made some exceptions to this – voluntary confessions allowed; no reading if in public safety interest; coerced confession allowed under “certain circumstances” Gideon v Wainwright (1963) – required states to provide lawyer for felonies if can’t afford; no guarantee that it’s a GOOD lawyer Death Penalty (Capital Punishment): Furman v Georgia (1972) – death penalty unconstitutional if applied unequally; Gregg v Georgia (1976) – death penalty not inherently unconstitutional if applied equally, reinstated; McClesky v Kemp (1988) - defendant can’t use trends & broad patterns to prove discrimination, must prove they personally were victims of intentional racial discrimination on part of prosecutor & jury. Later death penalty rulings allowed it against mentally retarded & minors, & limited appeals of those on death row (reflects that 70% of Americans support death penalty) Abortion Rulings: based on 9th amendment – implied right to privacy Griswold v Connecticut (1965) – said 1st, 3rd, 4th, & 9th amendments together create a “zone of privacy” & that state had violated it by passing a law against birth control advice Roe v Wade (1973) – extended “zone of privacy” to a woman’s body and therefore abortion; as a result all states must allow abortion during the first trimester but states can limit after that; set up an on-going debate over abortion ever since Further state restrictions on abortion rights: Webster v Reproductive Health Services (1989) – States do not have to used taxpayer money to pay for abortions, even if woman qualifies for Medicaid Planned Parenthood v Casey (1992) – said that laws requiring informed consent, 24 hour waiting period, permission of 1 parent for a minor (or judge’s consent) are not an undue burden for abortion; but requiring wife to notify husband before an abortion WAS an undue burden. Stenberg v Carhart (2000) – Pennsylvania. law against partial birth abortion ruled unconstitutional because didn’t include exception for mother’s health; Congress passed a law outlawing partial birth abortion (without the exception) in 2003 and it was ruled Constitutional by the new conservative majority Rulings on abortion clinic access – laws such as Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances which require anti-abortion protesters to be so many feet away from entrance are constitutional & not a violation on free speech but also can’t prosecute protesters under RICO (federal extortion/racketeering) laws. Constitutionally Protected Speech The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects freedom of speech, press, religion, and assembly and petition. The First Amendment reads as follows: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."(emphasis added) The First Amendment is applicable not just to Congress and the federal government, but to state and local public officials and entities as well, including UC San Diego. Protection of speech by the First Amendment is intended to encourage the free flow of ideas and to protect individuals whose speech may be considered unpopular or dissentious. While the First Amendment is very broad in its application, there are certain types of speech and expression that are not protected by the First Amendment. Attempts to regulate these types of unprotected speech generally fall into one of two categories: "content regulations" and "conduct regulations." Content Regulations Some laws and policies are drafted with the intention of preventing the expression of specific ideas and messages. Such attempts to regulate content are presumptively impermissible. Still, there are certain—though very limited—types of speech that are not protected by the First Amendment and are subject to regulation. However, despite the above exceptions, the First Amendment protects virtually all speech, no matter how unorthodox, offensive, or distasteful. See, e.g., United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310, 318 (1990); Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 414 (1989); Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 20 (1971). The categories listed above are extremely narrow, and courts will tend towards finding speech to be protected under the First Amendment, no matter how hateful or offensive it may be. Obscenity — Speech/materials may be deemed obscene (and therefore unprotected) if the speech meets the following (extremely high) threshold: It (1) appeals to the "prurient" interest in sex, (2) is patently offensive by community standards, and (3) lacks literary, scientific, or artistic value. Incitement — Activity or speech that advocates for producing 'imminent lawless action' and is likely to produce such action. Fighting words — Speech that is personally/individually abusive and is likely to incite imminent physical retaliation. Defamation — An intentional and false statement about an individual that is publicly communicated in written (called "libel") or spoken (called "slander") form, causing injury to the individual. Perjury — A knowingly false statement given under oath in court. Extortion — Obtaining property by wrongful use of force or fear. Harassment — A severe and pervasive course of conduct directed at an individual causing that person substantial emotional distress. True threat — A communicated intent to inflict death or great bodily harm to a person with an apparent ability to carry out the threat. False advertising — A knowingly untruthful or misleading statement about a product or service. Certain symbolic actions, if the actions are otherwise illegal. o Examples: Tagging/graffiti, littering, burning a cross on private property. Plagiarism of copyrighted material Child pornography Conduct (aka "Time, Place and Manner") Regulations Certain laws and policies (such as the UC San Diego Policy on Free Speech, Advocacy and Distribution of Literature on University Grounds) regulate the conduct pertaining to speech and expression, including the time, place, and manner of the speech, regardless of the content or message. Conduct regulations are more frequently protected by courts than content regulations so long as they are “content-neutral,” i.e., they do not attempt to forbid the communication of specific ideas. Regulations involving conduct may include criminal violations as defined by state law, such as disturbing the peace or disorderly conduct. Examples of permissible conduct regulations may include: o Time: Limiting amplified sound to certain hours. o Place: Prohibiting demonstrations at the entrance of campus buildings. o Manner: Limiting the size of flyers or signs at posting locations.